Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Did Anything Change? State Pension Legislation Before, During and After the Great Recession

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Michael Thom

November 4, 2014

The Great Recession had a profound impact on state and local governments. Many proposed cost reductions that included decreased contributions to public sector pensions, a move that generated heightened attention over other cost savings strategies. Yet an analysis of pension bills passed since 1999 suggests that states mostly continued practices that were in place before the recession.

The Great Recession had a profound impact on state and local governments. Many proposed cost reductions that included decreased contributions to public sector pensions, a move that generated heightened attention over other cost savings strategies. Yet an analysis of pension bills passed since 1999 suggests that states mostly continued practices that were in place before the recession.

Many legislatures proposed benefit cuts, implemented defined contribution accounts and limited cost-of-living allowances. Still others passed bills that actually increase costs and liabilities, a surprising result given rising costs and the recession’s lingering effects.

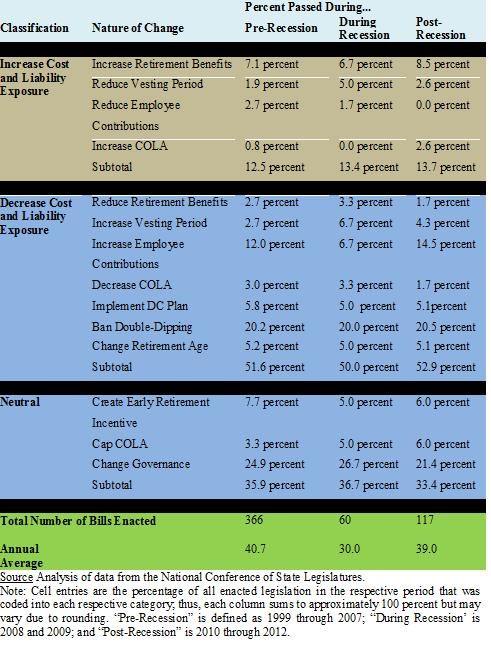

The table below classifies enacted legislation related to cost and liability exposure as increase, decrease or neutral. The right-hand columns indicate the percentage of legislation passed before, during and following the recession that fits into those categories.

These data offer intriguing insights about shifts before and after the recession. Regarding the latter period, a greater proportion of bills (9.7 percent) increased employee contributions and lengthened vesting periods—that is, the length of time an employee must work before qualifying for benefits. Many of the post-recession shifts are small (4.3 percent) and there is a fair amount of stasis otherwise. Bans on “double-dipping” remained as frequent after the recession as before, as was the enactment of defined contribution accounts.

In theory, heightened attention to pension costs should have caused a larger shift in legislative orientation toward benefit limits and reductions, increased employee costs and perhaps delayed eligibility. Yet actual patterns of legislative enactment do not indicate any systematic shift. Why not?

Several factors are likely at play. First, research has suggested that state and local governments generally have not confronted the economic challenges of the recession in a “transformational way.” Rather, they are “trying to get by and waiting for pressures to decrease.” That could well be the case with public sector pension reform.

Second, public sector labor unions have been effective at lobbying against reforms that would substantially alter how pensions are funded or would include greater use of defined contributions plans. Still, some states bucked the trend. In late 2011, over vocal union opposition, Rhode Island froze pension benefits and instituted a parallel defined contribution plan for state employees.

Third and most important, not all reforms are legally-feasible. Many states have extended constitutional protections to pension benefits, making it nearly impossible for policymakers to eliminate or even reduce stipends. Indeed, constitutional issues are at the core of pension reform debates. Public employees in San Jose, California recently sued the city over a voter-approved pension reform that increased employee contributions. A judge sided with them, arguing that constitutional protections forbade the city from raising employee costs.

More broadly, the failure of policymakers to shift the nature of pension legislation may simply be an illustration of the challenges inherent to democratic decision-making. Non-incremental reforms are notoriously difficult to pass because they face a higher risk of failure at multiple points in the policy process. Public sector pensions are no exception; in fact, many dispute that a funding problem exists in the first place. Even as Detroit proceeded through an $18 billion municipal bankruptcy case, the city’s labor unions disputed whether pension liabilities were as large as the city administration had claimed.

In situations like this one, where a consensus fails to form over the existence of a problem or its severity, political systems tend toward the path of least resistance. This suggests that even after a major economic shock, legislation passed after the event would continue to follow the same trajectory as before. That certainly appears to be the case for public sector pensions, with few exceptions.

Author: Michael Thom is assistant professor in the Price School of Public Policy at the University of Southern California. He can be reached at [email protected].

(8 votes, average: 4.50 out of 5)

(8 votes, average: 4.50 out of 5)

Follow Us!