Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Hurricane Awesome: The Politics of Naming Storms

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Amanda M. Olejarski

February 23, 2016

It’s a curious history of how hurricanes came to be named. Hurricanes have been named after saints, two different phonetic alphabets and even politicians. The first time proper names were used was in the late 1800s. Early proposed naming conventions included cities where the storm originated, the date or the threat level (Hurricane Awesome). In 1953, the practice began of naming hurricanes using women’s names only. Pacific storms incorporated men’s names in 1978 and Atlantic storms started the following year.

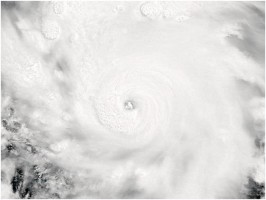

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) does not name hurricanes. That responsibility rests with the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). WMO has tropical cyclone committees to identify lists of names by region (Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico and North Atlantic Names, for example). Alternating men’s and women’s names, each annual list is on a six-year rotation. No, you cannot request to have a hurricane named after yourself (Hurricane Amanda, May 2014, as pictured). Hurricanes that are especially deadly or costly are retired, like Katrina and Sandy.

Why name hurricanes at all? WMO says,

“The main purpose of naming a tropical cyclone/hurricane is basically for people to easily understand and remember the tropical cyclone/hurricane in a region, thus to facilitate tropical cyclone/hurricane disaster risk awareness, preparedness, management and reduction.”

What about the shift in 1979 to using men’s and women’s names to identify hurricanes? Politics: “Under political pressure, the U.S. NHC requested that the WMO Region IV Hurricane Committee switch to a hurricane name list that alternated men’s and women’s names.” Activists from the National Organization for Women were vocal in opposing the use of only women’s names for hurricanes, advocating a return to using politicians’ names or even birds.

A 2014 study was published in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed “female-named storms have historically killed more because people neither consider them as risky nor take the same precautions.” A follow-up parsed potential methodological challenges. It is worth noting in the context of why storms are named— administrative communication during a potential crisis.

That is The Weather Channel’s (TWC) argument for why it began naming winter storms in 2012. A committee of three meteorologists uses a formula based on population and the area effected (2 million people and 400k square km) to name storms. TWC works with high school Latin Club students (Villa est villa Romana!) in Montana to identify the list of winter storm names, ensuring the names are “good hashtag material.”

The National Weather Service (NWS) isn’t involved in TWC’s winter storm naming process at all. A controversial debate has ensued. The NWS says that hurricanes are named because there are multiple storms occurring at the same time across international boundaries, noting that neither of those criteria exists with winter storms. TWC, however, returns with a broader case for improved communication and awareness that echoes the sentiments of the WMO. Tracking tweets using the winter storm name hashtag shows that government agencies and schools are using it. TWC’s public-service approach is that the name helps report weather data and results in better communication with the public.

Is TWC co-opting the storm naming process or are they filling a void that the NWS has left? Disputes between TWC and the NWS have erupted of late, mostly surrounding TWC’s vision for itself as a private organization that wants to be seen as providing a public service. Moreover, annual media usage of “snowmageddon,” “snowpocalypse,” and “snowzilla” will surely make historical record-keeping challenging. Calling it “the blizzard of ‘96” and “the blizzard of 2016” neglects all of the storms and subsequent lives lost and costly damage in between.

If the goal of naming storms is awareness and preparedness, then why not collaborate between the NWS and TWC to name winter storms? On one hand, WMO’s rationale for naming hurricanes is to facilitate communication with the public, but the narrower scope of the NWS is to alleviate confusion. Since the NWS isn’t involved in the naming process for hurricanes, partnering with TWC could present a new opportunity for both organizations. Modernizing the NWS using social media aligns with public expectations, and marketing TWC as a public-service provider returns a sense of legitimacy.

That still leaves the “what” question up for debate: what should storms be named after? If the National Audubon Society can stop hurricanes from being named after birds, what remains as a viable option? It would need to be something without interest group support or collective backing. Turning optimistically to my social media network for alternatives was disheartening; someone thought of how even mulch might be problematic. Mulch.

Author: Amanda M. Olejarski is an associate professor in West Chester University’s Department of Public Policy and Administration and serves as president-elect of the Central Pennsylvania Chapter of ASPA. She can be contacted at [email protected] or on LinkedIn.

Follow Us!