The Personal Accountancy Lens of Society’s Intimate Partner Violence

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Nicholas Mastron

September 22, 2017

In 1994, the federal government officially recognized intimate partner violence (IPV) as a public problem through the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and its subsequent regulations and reauthorizations.

Executive Orders 12866 and 13563, though, direct agencies toward regulatory impact analyses to quantify and estimate the efficacy of regulations, such as those under VAWA. Historically, most VAWA IPV regulations have relied upon the “other compelling public need” clause as a means around regulatory impact, but in recent years both members of Congress and the American public have decreasingly accepted this philosophy.

Hence, to protect the future of IPV regulations and legislation like VAWA, American academics and policymakers need to better understand IPV cost estimation techniques.

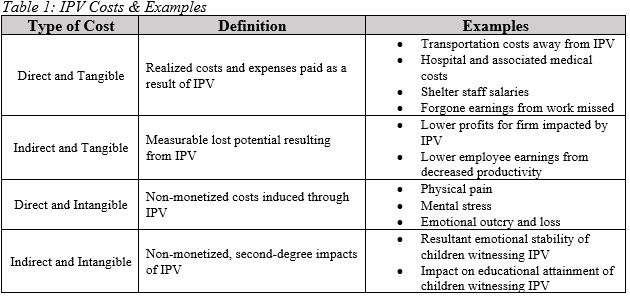

A recent United Nations report considered four IPV costs: direct tangible, indirect tangible, direct intangible and indirect intangible. Definitions and examples of these costs are subsequently provided in Table 1 below.

Currently, practitioners and scholars account for these types of IPV costs primarily through four methods: direct accounting, present value discounting, contingent value modeling and disability adjusted life years (DALY) factoring.

Direct accounting, perhaps most intuitive of these methods, tracks individual tangible costs accrued through someone’s experience with IPV. So, one could envision a top-down approach––with IPV prevalence and associated response mechanisms’ costs and utilizations––or even a bottom-up approach that incorporates a selected sample’s costs of IPV-specific response services used or impacts rendered from IPV.

However, sincere methodological drawbacks plague this method. Survivors often under-report (or do not even know) their experienced survival costs. The diversity of costs incurred during various IPV stages represents another challenge, and even then, many goods’ and services’ prices regularly fluctuate irrespective of IPV prevalence.

The parametric approach of present value discounting better measures IPV’s indirect tangible costs related to lost productivity and human capital impacts. Here, IPV’s empirical impact to wages and production variables fluctuates over time by accounting for perceived benefit in present versus future periods. Some may think to simply apply the “traditional” federal 3 percent and 7 percent rates simultaneously to construct a range of IPV economic impact, but this practice assumes these nationally standardized rates equal to IPV prevalence, which proves problematic and potentially false. Furthermore, present value discounting assumes strict causality between IPV and these economic factors, ignoring any variable reciprocity.

Since IPV studies seek the public’s value of not experiencing a trauma, another cost estimation tool is common within regulatory analyses is contingent value (CV) modeling. Also known as willingness-to-accept (WTA) modeling, this method constructs a society’s IPV allowance and thereby its social costs through ex-post jury awards for IPV survivors.

Thus, natural comparison survivor groups, created by matching survivors’ and defendants’ case details, underpin this technique’s statistical conclusion validity. These studies assume comparability to public willingness to avoid similar injuries from non-IPV incidents. This assumption poses two major ethical dilemmas. First these groupings display a callous decision rule that may ostracize survivor participation in any face-to-face settings, invoking an ethical concern. Similarly controversial, contingent valuation creates a sample value of a statistical life (VSL) among IPV survivors, which implies that more affluent victims and juries would receive higher values.

A final IPV cost estimation technique, disability adjusted life years (DALYs) factoring, estimates the value of life experience and utility lost due to IPV violence, historically those resulting from acts of physical violence. While challenging to translate years of life lost from IPV, based upon initial life expectancies, this method in a traditional cost-benefit analysis framework could construct IPV cost-utility, avoiding any monetization all together.

=While studies often mix these non-exclusionary methods in analyses, these techniques only placate the federal government’s growing insistence on cost-benefit analysis. Yet, as more academic journals, think tanks and legislative requirements turn to praise cost-benefit analysis in policymaking, increased understanding and utilization of these IPV cost estimation tools will better safeguard prevention programs and services’ funding.

These accountancy frameworks, while individually imperfect, do provide a more personal lens by which surviving IPV can be communicated empirically. As such, scholars and practitioners alike should expand their usage to better help folks undergoing personal tumult by building better outcomes.

Author: Nicholas Mastron is a current PhD student in Public Policy & Administration at the George Washington University, with a field specialization in Gender & Social Policy. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him @NicholasMastron.

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

Loading...

Loading...

The Personal Accountancy Lens of Society’s Intimate Partner Violence

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Nicholas Mastron

September 22, 2017

In 1994, the federal government officially recognized intimate partner violence (IPV) as a public problem through the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and its subsequent regulations and reauthorizations.

Executive Orders 12866 and 13563, though, direct agencies toward regulatory impact analyses to quantify and estimate the efficacy of regulations, such as those under VAWA. Historically, most VAWA IPV regulations have relied upon the “other compelling public need” clause as a means around regulatory impact, but in recent years both members of Congress and the American public have decreasingly accepted this philosophy.

Hence, to protect the future of IPV regulations and legislation like VAWA, American academics and policymakers need to better understand IPV cost estimation techniques.

A recent United Nations report considered four IPV costs: direct tangible, indirect tangible, direct intangible and indirect intangible. Definitions and examples of these costs are subsequently provided in Table 1 below.

Currently, practitioners and scholars account for these types of IPV costs primarily through four methods: direct accounting, present value discounting, contingent value modeling and disability adjusted life years (DALY) factoring.

Direct accounting, perhaps most intuitive of these methods, tracks individual tangible costs accrued through someone’s experience with IPV. So, one could envision a top-down approach––with IPV prevalence and associated response mechanisms’ costs and utilizations––or even a bottom-up approach that incorporates a selected sample’s costs of IPV-specific response services used or impacts rendered from IPV.

However, sincere methodological drawbacks plague this method. Survivors often under-report (or do not even know) their experienced survival costs. The diversity of costs incurred during various IPV stages represents another challenge, and even then, many goods’ and services’ prices regularly fluctuate irrespective of IPV prevalence.

The parametric approach of present value discounting better measures IPV’s indirect tangible costs related to lost productivity and human capital impacts. Here, IPV’s empirical impact to wages and production variables fluctuates over time by accounting for perceived benefit in present versus future periods. Some may think to simply apply the “traditional” federal 3 percent and 7 percent rates simultaneously to construct a range of IPV economic impact, but this practice assumes these nationally standardized rates equal to IPV prevalence, which proves problematic and potentially false. Furthermore, present value discounting assumes strict causality between IPV and these economic factors, ignoring any variable reciprocity.

Since IPV studies seek the public’s value of not experiencing a trauma, another cost estimation tool is common within regulatory analyses is contingent value (CV) modeling. Also known as willingness-to-accept (WTA) modeling, this method constructs a society’s IPV allowance and thereby its social costs through ex-post jury awards for IPV survivors.

Thus, natural comparison survivor groups, created by matching survivors’ and defendants’ case details, underpin this technique’s statistical conclusion validity. These studies assume comparability to public willingness to avoid similar injuries from non-IPV incidents. This assumption poses two major ethical dilemmas. First these groupings display a callous decision rule that may ostracize survivor participation in any face-to-face settings, invoking an ethical concern. Similarly controversial, contingent valuation creates a sample value of a statistical life (VSL) among IPV survivors, which implies that more affluent victims and juries would receive higher values.

A final IPV cost estimation technique, disability adjusted life years (DALYs) factoring, estimates the value of life experience and utility lost due to IPV violence, historically those resulting from acts of physical violence. While challenging to translate years of life lost from IPV, based upon initial life expectancies, this method in a traditional cost-benefit analysis framework could construct IPV cost-utility, avoiding any monetization all together.

=While studies often mix these non-exclusionary methods in analyses, these techniques only placate the federal government’s growing insistence on cost-benefit analysis. Yet, as more academic journals, think tanks and legislative requirements turn to praise cost-benefit analysis in policymaking, increased understanding and utilization of these IPV cost estimation tools will better safeguard prevention programs and services’ funding.

These accountancy frameworks, while individually imperfect, do provide a more personal lens by which surviving IPV can be communicated empirically. As such, scholars and practitioners alike should expand their usage to better help folks undergoing personal tumult by building better outcomes.

Author: Nicholas Mastron is a current PhD student in Public Policy & Administration at the George Washington University, with a field specialization in Gender & Social Policy. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him @NicholasMastron.

Follow Us!