Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Speaking Truth to Power

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Terry Newell

October 11, 2016

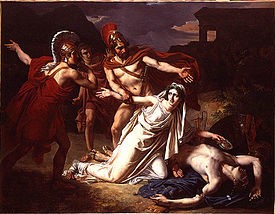

“Nobody likes the messenger who brings bad news,” said the palace guard, afraid to tell King Creon that Antigone had buried her brother, against his orders. Twenty-five hundred years after Sophocles wrote this tragedy, the need for leaders to hear the truth and the reluctance of followers to share it is still a challenge.

“Nobody likes the messenger who brings bad news,” said the palace guard, afraid to tell King Creon that Antigone had buried her brother, against his orders. Twenty-five hundred years after Sophocles wrote this tragedy, the need for leaders to hear the truth and the reluctance of followers to share it is still a challenge.

The Scope of the Problem

The failure to speak truth to power can lead to organizational embarrassment and failure. In both the Challenger and Columbia space shuttle disasters, the causes were known beforehand by some in NASA but were not communicated to top leaders. As the Columbia Accident Investigation Board said about both tragedies, ” . . . people were silenced, and useful information and dissenting views . . . did not surface at higher levels.”

Many employees are afraid to tell the truth to leaders. In its 2015 survey of federal workers, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management found one in five had a “fear of reprisal” if they disclosed “a suspected violation of any law, rule or regulation.” Nearly 20 percent more were not sure if they could safely do so.

What Employees Can Do

In1960, Frances Oldham Kelsey was a physician reviewing drugs for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). When asked to approve thalidomide, whose manufacturer said it would aid pregnant women with morning sickness, she refused, demanding further studies. In doing so, despite intense pressure from the manufacturer, she prevented birth defects in untold thousands of American babies. This took moral courage, essential for speaking truth to power.

In his book, Moral Courage, Rush Kidder describes three elements needed to speak truth to power. One must (1) have a moral principle at stake, (2) realize the danger in speaking out, and (3) exhibit endurance – the ability to push forward in spite of the danger.

The trick is how to exhibit endurance while mitigating the danger (to your job, reputation, etc). In other words, how can you press ahead without committing career suicide? Joseph Badaracco, Jr. offers an answer in Leading Quietly. Often the most effective way to speak the truth to power is to do so without drawing a line in the sand or becoming a public whistleblower. The “quiet” leader uses eight techniques.

1. Don’t Kid Yourself – that you know all you need to know.

2. Trust Mixed Motives – it’s OK to be worried about doing the right thing and your career.

3. Buy a Little Time – to work the problem.

4. Invest Wisely – use your political capital judiciously.

5. Drill Down – gather the facts you need.

6. Bend the Rules – look for flexibility in ways to do the right thing.

7. Nudge, Test and Escalate Gradually – push back, gently but persistently.

8. Craft a Compromise – be willing to compromise to see that the right thing gets done.

What Leaders Can Do

In an early meeting with direct reports during World War II, Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall was concerned they were reluctant to tell him what they thought. “Gentlemen, I am disappointed in you. You haven’t yet disagreed with a single decision I’ve made,” he said. He thus took the single most important step in creating a climate of candor.

Leaders can take steps beyond acknowledging the problem and modeling the behavior they expect. They can:

- Reduce the cultural pressure for obedience to authority.

Before the failed Bay of Pigs effort to topple Castro in 1961, those with reservations about the plan were or were encouraged to stay silent. President Kennedy learned from this mistake. As his Special Assistant, Theodore Sorenson said later about the Cuban Missile Crisis: “I said to him that people were more likely to speak frankly when he was not there and they were not embarrassing their boss by speaking against him.” So Kennedy sometimes stayed away from the deliberations until the group had a recommendation to make.

- Establish dissent channels.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has a formal “Differing Professional Opinion” process that allows any employee to express concern about a pending action, and have the concern heard in an objective way. The State Department has a formal “dissent channel” that allows employees to disagree without reprisal.

- Reward dissent.

For her action, Kelsey received the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. On the 50th anniversary of her courageous act, the FDA Commissioner created the Kelsey Award, an honor to be given to FDA employees who “celebrate courage and scientific decision-making.”

“The only thing necessary for evil to triumph is for good people to do nothing,” British statesman and writer Edmund Burke said. There is a lot “good people” – public servants and their leaders – can do to ensure the truth reaches the top in their organizations.

Author: Terry Newell is president of his training firm, Leadership for a Responsibility Society and is the former dean of faculty of the Federal Executive Institute. His latest book is titled, To Serve with Honor: Doing the Right Thing in Government. Email: [email protected].

Follow Us!