Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

The Spratly Islands

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By David Howard Davis

January 26, 2016

When I was a Fulbright professor at the School of the Environment in Nanjing, China, seven years ago, I watched a lot of Channel 9 on television. I couldn’t help it. It was the only English language station at my on-campus apartment. Channel 9 (CCTV) is a 24-hour news broadcast operated by the government. It is, of course, heavily censored and gives the official point of view. It is literally the party line. Besides news, Channel 9 broadcasts sports, music and travelogues.

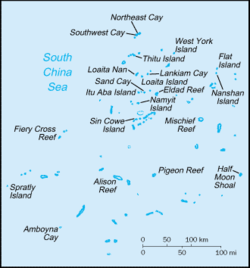

Soon I began to see frequent stories about the Spratly Islands, a place I had never heard of before. These turned out to be a desolate group of coral reefs, shoals and low-lying islands in the South China Sea. The newscasters earnestly told of how they were historically part of China. The propaganda campaign was underway. Now, seven years later, the People’s Republic has ramped up its propaganda and naval campaign. Incredibly, it is dredging sand and coral to increase the size and height above sea level.

My first reaction was why did anyone care? The world soon learned that China was eager to claim the islands for their natural resources. Supposedly, the surrounding seabed contained valuable oil and gas deposits. China wanted to establish a 200-mile exclusive economic zone around the islands under the provisions of the Law of the Sea.

This raised two environmental issues. First was the nature of the islands and shoals. Were they really islands? Coral are nearly microscopic marine organisms that build calcium structures in which they live. It is a scientific fact that they cannot grow above the water, hence cannot form an island. Of the hundreds of features in the South China Sea, only a few rise above the ocean surface and they are only a few acres in extent. The Law of the Sea defines an island as “a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide” and says, “rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no Exclusive Economic Zone.”

The second environmental issue is the extent of oil and gas in the seabed. Press accounts routinely assert these are large, but evidence is lacking. A few years ago, Vietnam drilled exploratory wells in the area, but gave up after not finding commercial quantities. Although China has numerous rigs exploring the Sea, it has announced no finds. Indeed, it may be that the area lacks sufficient oil and gas reserves.

Thus, environmental factors fail to explain the People’s Republic aggressiveness. Since Xe Jinping became president in 2012, the country has become belligerent. It has increased its Navy, adding ships and sailors. It has built airstrips on the “islands” with sand and coral dredged up from the sea. It has warned foreign navies and air forces not to approach within 12 miles and not to overfly them.

This aggressiveness is a departure from past Chinese foreign policy. The Middle Kingdom enjoys natural defenses. To the east, it is protected by the ocean, to the west by the Himalaya Mountains and deserts, to the north by cold and barren land unsuitable for agriculture and to the south by mountains and jungles. Of 14 border conflicts since the Communists came to power in 1949, virtually all were settled by compromise.

An alternative would be to negotiate under the Law of the Sea. A model would be dividing the North Sea between Britain, Norway and four other countries in 1967 when oil and gas were discovered. Submitting the issue to the LOS International Tribunal could also settle the issue. A major company like Exxon or BP is unlikely to invest in production wells until the legal rights are settled, yet China has refused to do so. Last October, the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague ruled it had jurisdiction over the case disputed with the Philippines, but China rejected the ruling.

The conflict in the South China Sea presents a conundrum. Environmental science demonstrates the “islands” are not really islands and the oil and gas is probably not commercially available. Analysis of foreign policy suggests the policy is atypical and unnecessary. International law offers a practical solution, but China rejects this.

Author: Davis teaches environmental policy at the University of Toledo. He thanks Mely Arribas-Douglas for her help in this article. Email [email protected].

(5 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(5 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

Follow Us!