State Budgeting: You Can Bend but Never Break Me

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Jason Juffras

September 5, 2017

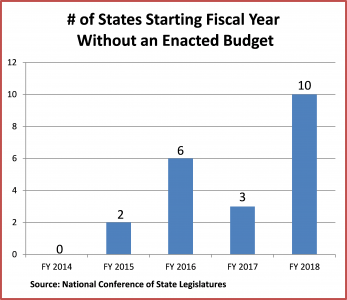

State budget observers have expressed alarm that 10 states had not enacted budgets by the start of fiscal year (FY) 2018, which began on July 1 in 46 states. Budget dysfunction—the delayed appropriations and threatened shutdowns, with a sprinkling of harsh rhetoric—has permeated the federal government. But states, those “laboratories of democracy” that are closer to the people, have usually followed a more cooperative and competent way of budgeting. Do the FY 2018 state budget stalemates signal this tradition might end?

In short, the answer is no. State budgeting is subject to serious economic, political and social pressures, but key institutional features should help states withstand the strains. Almost all states face legal requirements to balance their operating budgets, as well as scrutiny from those who purchase and rate their bonds. Moreover, voters in each state—whether a “blue” state like Massachusetts or a “red” state like Texas—are usually more similar in ideology than the nation as whole, which should make it easier for state leaders to agree on budgets and the policy choices they involve.

Let’s look more closely at this year’s state budget deadlocks.

Budget failures in states such as Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts and New Jersey reflected the ideological stalemate associated with divided government, where neither party controls the governor’s office and both houses of the legislature. In New Jersey, a dispute over Blue Cross/Blue Shield reserves between Republican Governor Chris Christie and Democratic House Speaker Vincent Prieto, led to a brief government shutdown over the July 4 weekend. Similar clashes in prior years and an unwillingness to make hard choices have left New Jersey with a large unfunded pension liability and a designation by the Mercatus Center as the state in the worst financial condition.

Still, state budget dysfunction also occurred in states where the executive branch and legislature are controlled by the same party (“unified government”), such as Connecticut, Michigan, Rhode Island and Wisconsin. In Connecticut, Democratic Governor Dannel Malloy and legislators could not agree on how to close a two-year, $5 billion budget gap caused in part by slow revenue growth, leading Malloy to curtail social service and other programs by executive order.

If state budget breakdowns happen under divided and unified governments, and in blue and red states, can states continue to avoid the pervasive dysfunction of federal budgeting? Strong forces continue to pull states back from the budget brink – or help them climb back up when they’ve gone over the edge. States must finance education, health care, and transportation (at least at some level); balance their budgets; and maintain good credit ratings to access capital markets at reasonable cost. By early August, only two of the 11 states that began FY 2018 without enacting a budget (Connecticut and Wisconsin) still lacked an agreement. In Maine, Republican Governor Paul LePage (who described himself as “Donald Trump before Donald Trump”) reopened state government on July 4after accepting increased education spending in return for the legislature’s decision to rescind a lodging tax hike.

The pragmatic need to keep state government functioning can even overcome lawmakers’ aversion to tax increases. In Illinois, where Governor Bruce Rauner and a Democrat-controlled legislature had not enacted a budget since 2015, enough Republican legislators joined with Democratic colleagues this year to override Rauner’s veto of a $36 billion budget with $5 billion in tax increases. A key motivation was the threat by credit-rating agencies to downgrade Illinois’ bonds to junk status. In Kansas, a legislature controlled by Republicans overrode Governor Sam Brownback’s veto of a bill that rolls back large tax cuts that had created large budget shortfalls and decimated state programs. It’s hard to imagine congressional Republicans and Democrats joining forces to enact tax increases over the veto of a Republican president, but such bipartisan coalitions still occur at the state level.

Unfortunately, the self-corrective mechanisms of state budgeting may not turn on before considerable damage is done. Illinois now has a budget, but still faces a pension liability of more than $100 billion as well as $15 billion in unpaid bills. Alaska legislators approved a budget the day before FY 2018 started, but nearly drained the state’s reserve fund. Shortly thereafter, Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s both downgraded Alaska’s credit rating.

State budgeting continues to function well in many states, but is beset by economic, political and social pressures that impose major costs, including delayed or non-existent responses to changing societal needs. A stronger political center, and a willingness to bargain and build consensus, may be needed to help state policymakers budget effectively in a time of slow revenue growth, rising health care costs, delayed costs for pensions and infrastructure, and federal spending cutbacks.

Author: Jason Juffras has 20 years of experience in state and local budgeting, policymaking, and program evaluation. He earned a doctorate in public policy and administration from The George Washington University in 2015, with a concentration in public budgeting and finance. He can be reached at [email protected].

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

Loading...

Loading...

State Budgeting: You Can Bend but Never Break Me

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Jason Juffras

September 5, 2017

State budget observers have expressed alarm that 10 states had not enacted budgets by the start of fiscal year (FY) 2018, which began on July 1 in 46 states. Budget dysfunction—the delayed appropriations and threatened shutdowns, with a sprinkling of harsh rhetoric—has permeated the federal government. But states, those “laboratories of democracy” that are closer to the people, have usually followed a more cooperative and competent way of budgeting. Do the FY 2018 state budget stalemates signal this tradition might end?

In short, the answer is no. State budgeting is subject to serious economic, political and social pressures, but key institutional features should help states withstand the strains. Almost all states face legal requirements to balance their operating budgets, as well as scrutiny from those who purchase and rate their bonds. Moreover, voters in each state—whether a “blue” state like Massachusetts or a “red” state like Texas—are usually more similar in ideology than the nation as whole, which should make it easier for state leaders to agree on budgets and the policy choices they involve.

Let’s look more closely at this year’s state budget deadlocks.

Budget failures in states such as Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts and New Jersey reflected the ideological stalemate associated with divided government, where neither party controls the governor’s office and both houses of the legislature. In New Jersey, a dispute over Blue Cross/Blue Shield reserves between Republican Governor Chris Christie and Democratic House Speaker Vincent Prieto, led to a brief government shutdown over the July 4 weekend. Similar clashes in prior years and an unwillingness to make hard choices have left New Jersey with a large unfunded pension liability and a designation by the Mercatus Center as the state in the worst financial condition.

Still, state budget dysfunction also occurred in states where the executive branch and legislature are controlled by the same party (“unified government”), such as Connecticut, Michigan, Rhode Island and Wisconsin. In Connecticut, Democratic Governor Dannel Malloy and legislators could not agree on how to close a two-year, $5 billion budget gap caused in part by slow revenue growth, leading Malloy to curtail social service and other programs by executive order.

If state budget breakdowns happen under divided and unified governments, and in blue and red states, can states continue to avoid the pervasive dysfunction of federal budgeting? Strong forces continue to pull states back from the budget brink – or help them climb back up when they’ve gone over the edge. States must finance education, health care, and transportation (at least at some level); balance their budgets; and maintain good credit ratings to access capital markets at reasonable cost. By early August, only two of the 11 states that began FY 2018 without enacting a budget (Connecticut and Wisconsin) still lacked an agreement. In Maine, Republican Governor Paul LePage (who described himself as “Donald Trump before Donald Trump”) reopened state government on July 4after accepting increased education spending in return for the legislature’s decision to rescind a lodging tax hike.

The pragmatic need to keep state government functioning can even overcome lawmakers’ aversion to tax increases. In Illinois, where Governor Bruce Rauner and a Democrat-controlled legislature had not enacted a budget since 2015, enough Republican legislators joined with Democratic colleagues this year to override Rauner’s veto of a $36 billion budget with $5 billion in tax increases. A key motivation was the threat by credit-rating agencies to downgrade Illinois’ bonds to junk status. In Kansas, a legislature controlled by Republicans overrode Governor Sam Brownback’s veto of a bill that rolls back large tax cuts that had created large budget shortfalls and decimated state programs. It’s hard to imagine congressional Republicans and Democrats joining forces to enact tax increases over the veto of a Republican president, but such bipartisan coalitions still occur at the state level.

Unfortunately, the self-corrective mechanisms of state budgeting may not turn on before considerable damage is done. Illinois now has a budget, but still faces a pension liability of more than $100 billion as well as $15 billion in unpaid bills. Alaska legislators approved a budget the day before FY 2018 started, but nearly drained the state’s reserve fund. Shortly thereafter, Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s both downgraded Alaska’s credit rating.

State budgeting continues to function well in many states, but is beset by economic, political and social pressures that impose major costs, including delayed or non-existent responses to changing societal needs. A stronger political center, and a willingness to bargain and build consensus, may be needed to help state policymakers budget effectively in a time of slow revenue growth, rising health care costs, delayed costs for pensions and infrastructure, and federal spending cutbacks.

Author: Jason Juffras has 20 years of experience in state and local budgeting, policymaking, and program evaluation. He earned a doctorate in public policy and administration from The George Washington University in 2015, with a concentration in public budgeting and finance. He can be reached at [email protected].

Follow Us!