Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

On My Desk: Paralyzing DEI

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Grant E. Rissler

May 23, 2025

Among the recent articles published in Administrative Theory & Praxis (ATP) is Paralyzing DEI: A critical analysis of anti-CRT legislation by Addrain Conyers and Christina Wright Fields. The article extends the Institutional Racial Paralysis framework to help illuminate a range of actions by state legislatures and the new Trump administration that target Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) focused efforts.

Our house is 20th century enough that we still get a Sunday paper delivered. On a recent Sunday morning, one front page headline read “Trump Seeks to Strip Away Legal Tool Key to Civil Rights Enforcement.” A recent article in Administrative Theory & Praxis (ATP) by Addrain Conyers and Christina Wright Fields titled “Paralyzing DEI: A critical analysis of anti-CRT legislation” provides insight on this and other deployments of federal executive and state legislative power to push back against the use of tools that allow administrators and the public to “see” persistent inequality.

The Times article detailed how “a little noticed order” signed on April 23, 2025 (the “Restoring Equality of Opportunity and Meritocracy”) ordered federal agencies to “curtail the use of ‘disparate-impact liability,’ a core tenet used for decades to enforce the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by determining whether policies disproportionately disadvantage certain groups.” (Those wanting a more detailed understanding of disparate impact and ways to avoid it may find this Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM) toolkit helpful.)

At the same time, the article notes, “the use of the disparate-impact rule…has also long been a target of conservatives who say that employers and other entities should not be scrutinized and penalized for the mere implication of discrimination, based largely on statistics. Instead, they argue that such scrutiny should be directed at the explicit and intentional discrimination prohibited by the Civil Rights Act.”

Defining Racism and Other Forms of Oppression

As a white male in U.S. society who benefited from the insights of anti-oppression training, I remember finding the following definition of oppression (racism) helpful:

Oppression (Racism) = (racial) prejudice + Power

Important in my own learning was the insight that prejudice or prejudging is not the only element of oppression—the key is the power to impose that prejudice on others. Said another way, prejudice, which is a universal impulse in human societies, may be something to work on as we learn more about the people and the world around us, but it is not in the same category of harm without the addition of power. Yet prejudice is often the focus of discussions about intentional discrimination and the conservative argument against disparate impact analysis that focuses solely on intentional discrimination (also known as disparate treatment) implicitly suggests that persons in positions of responsibility should be absolved of any unintentional discrimination that disparate impact analysis attempts to make visible, a stance that is at odds with the ethical frameworks that operate in our society (e.g. we make a distinction between first degree (intentional) murder and (unintentional) manslaughter, but persons are still held accountable for the outcomes of their action).

The levels at which power is exercised is another key insight I found helpful in anti-oppression training. We often begin educating our children about values at an individual level (encouragement to share a toy with another child) but we also know that institutional power shapes our lives in important ways (among other reasons, we pay taxes and create governments to share the benefits of public safety more broadly than we could each manage on our own). Our individual power interacts with institutional power, whether talking about the responsibility/privilege of voting in a democracy or about the amplified power one person has when stepping into an institutional role (like a teacher in a classroom or a manager of a department). When disagreements occur, people within institutions often use both our individual power (and prejudices) and our institutional amplification to push on other institutions to change their actions.

Of course there is a host of writing, teaching and research that explores these insights in greater depth and better prose than my own—much of it cited by Conyers and Wright Fields in their article “Paralyzing DEI”—but the idea that power, including institutional power, is a key part of societal change and oppression within our society is a helpful thing to keep in mind as we turn to their insights.

The Institutional Racial Paralysis (IRP) framework

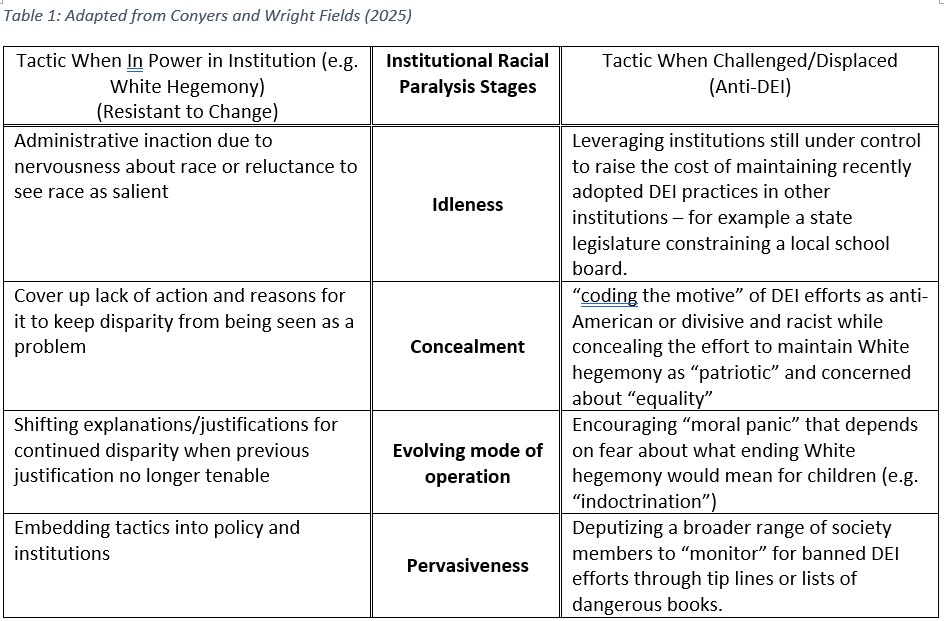

Conyers and Wright Fields utilize an Institutional Racial Paralysis (IRP) framework previously developed in 2021 to explain ways that (racial) power within institutions resists change (when in a dominant position). They use the same basic framework here to analyze examples of anti-Critical Race Theory (CRT) and anti-Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) legislation at the state level that responded to the more widespread adoption of DEI initiatives following 2020 racial justice protests. Published just before President Trump’s second inauguration, the article nevertheless grants insight to recent Trump administration actions that seek to nationalize the anti-DEI efforts through federal power—actions like the order to end disparate impact analysis of liability. The framework used highlights four stages of IRP in action (see the central column of Table 1) and Conyers and Wright Fields recap from their 2021 work how this operates in institutions where white norms have been the standard (and DEI efforts are challenging those norms—left hand column) and then extend it to situations where legislatures are pushing back against DEI efforts that established institutional footholds. (Table 1 represents my attempt to summarize their more in-depth discussion—any oversimplification or error in doing so is mine and not the authors’.)

Key insights of this framework that I find helpful include the following:

- The framework helps identify what to expect when racial disparity is argued to be a relevant factor in defining a problem—first to ignore (not see), then to find ways to conceal (to unsee) the disparity in question. Revoking the use of disparate impact analysis, as well as taking down data sets that break down outcomes by racial category, represent institutional efforts to “unsee” what had become a standard question to ask in professional administrative contexts.

- The framework’s focus on a quest for pervasiveness (in not seeing race in a way that is defined as a moral problem) illuminates the battle for institutional terrain that is much more explicit under the new Trump administration, and which relies on the creation of “moral panic” to justify the actions.

Relevance to Public Administrators

Public administrators understand that the federal system in the United States provides myriad ways for institutions at federal, state and local levels to leverage their own institutional power to shape policies at other levels. While the profession of public administration has increasingly seen equity as a foundational pillar of good governance and white hegemony has lost some institutional terrain within the profession since the Civil Rights Movement, the article by Conyers and Wright Fields provides insight into how other institutions in society, from state legislatures to the White House, may be used to push the profession back into idleness when it comes to persistent racial and other important inequalities. Public administrators, both individually and collectively, will need to gut check their values and decide whether the increased commitment to equity remains an anchor at our professional core.

Conclusion

Amid current efforts to significantly reshape the role of the federal government and whether racial disparities should still be seen, or seen as a problem, paying attention to how the power of institutions are being used to see or obscure inequality and support or oppose greater equality remains a needed and basic commitment of those who administer public organizations.

Author: Grant Rissler is Assistant Professor of Organizational Studies at the School of Professional and Continuing Studies, University of Richmond (VA). He serves on the editorial board of Administrative Theory & Praxis (ATP) and focuses his research on social equity and peacebuilding with particular interest in local government responsiveness to immigrants. The “On My Desk” series of columns, begun in July 2024, intentionally highlights the insights of one or more articles published in ATP in relation to a current debate or event. Grant can be reached at [email protected].

Follow Us!