Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

On My Desk: The 2024 Global Peace Index

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Grant E. Rissler

July 5, 2024

Discussing the concept of peace helps highlight how the decision of what to measure can shape the goals we set as public administrators.

In public administration, the things we measure, and how we decide to measure them, inherently shape the goals we set using those measurements. While this is true of tangible accomplishments—new housing starts, the number of trees planted or potholes filled—it is especially true of less tangible goals like effectiveness, equity or peace, a topic that landed in my inbox this past month with the release of the 2024 Global Peace Index, a report compiled for the last 17 years by the Institute for Economics & Peace.

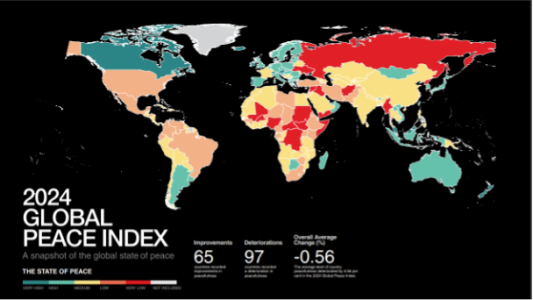

The report contains a number of interesting findings. The countries who ranked highest (out of 163 that were evaluated) were Iceland, Ireland, Austria, New Zealand and Singapore; the bottom five were Yemen, Sudan, South Sudan, Afghanistan and Ukraine. Ninety-seven countries saw a deterioration this past year in peacefulness while 65 recorded improvements. The countries with the largest deterioration in peacefulness in the past year were Israel, Ecuador, Gabon, Palestine and Haiti. The Institute calculated the economic impact of violence on the global economy at $19.1 trillion or about $2,380 per person.

But the report also highlights the key question of how one can measure something like peace and it reminded me of an exchange I had some years ago.

Earlier in my career, I worked as East Coast (of the U.S.) Peace & Justice Coordinator for Mennonite Central Committee, a faith-based relief, development and peace-building non-profit. The role connected supporting congregations to advocacy efforts that supported peace-building activities and highlighted the ways that conflict and war can often wipe out years of economic and community development in a short time—but none of that was apparent from the title.

Shortly after I started the job, I went to my high school reunion. A classmate, who I had not seen since we graduated and who was recently returned from service with the U.S. military in Iraq, responded to my recitation of my job title with a hearty laugh and declared “that must be the easiest job in the world—there hasn’t been a war on the East Coast of the U.S. in more than 150 years!”

Reading through the report, I was reminded of this exchange. The United States dropped two spots in the ranking of 163 countries—to 132nd—just below Brazil and just above Iran. How does a country like the United States with very few instances of war on its own soil in the last century rank so low?

My high school classmate used the simplest measurement of a “negative peace”—no open war = peace. The Global Peace Index, by contrast, uses a much more complex measurement, but one still based on negative peace. In ranking countries, and in measuring whether peace has increased or decreased in the past year, the index measures three dimensions of peace with a range of individual indicators rolled up into each dimension:

- Ongoing domestic and international conflict as measured by six indicators, including the number of deaths from internal organized conflict;

- Societal Safety & Security as measured by eleven indicators, including the number of homicides per 100K population and the ease of access to small arms and light weapons;

- Militarization as measured by six indicators, including military expenditure as a percentage of GDP.

Moving from a very simple measure of peace to one with greater complexity highlights not only overt large-scale conflicts (e.g. civil war) but also the cost of numerous smaller conflicts (e.g. homicides).

Yet another take on peace is a conceptual shift from the negative framing toward “positive peace”—a lack of overt conflict that also includes justice or right relationships within society. The Institute for Economics and Peace also generates a Positive Peace report. Here the indicators measured are those that have been shown to have the strongest relationship with the absence of violence or fear of violence and include dimensions such as “low levels of corruption,” a “well-functioning government” and a “sound business environment.” These sorts of indicators are familiar territory for public administrators.

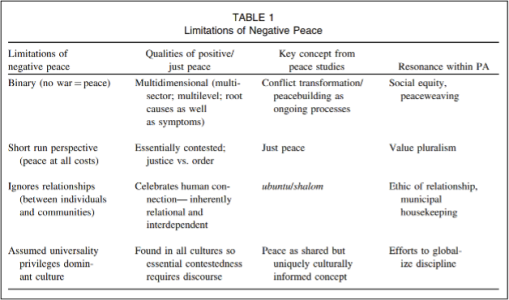

Patricia Shields and I argue in our 2019 article “Positive Peace: A Necessary Touchstone for Public Administration” in the journal Administrative Theory & Praxis that a positive peace framing pushes our awareness towards things that are missed in a negative peace framework. The table below from that article outlines several ways that a positive peace framing overcomes some of the limitations of negative peace.

1 – From Positive Peace – A Necessary Touchstone for Public Administration by Grant Rissler and Patricia Shields in Administrative Theory & Praxis – Copyright 2018 Public Administration Theory Network

Relevance to Public Administrators

This shift in framing can be useful to public administrators because it encourages looking beyond measurement of negative peace rooted indicators such as a drop in violent crimes (valuable as that is) and to also focus on measuring and setting goals around different indicators. A positive peace view pays attention to power differentials between members of society and to the structures of listening that shape what society sees as a problem in need of fixing. For example, a social equity analysis related to how different groups have different access to public services pays attention to power differentials and relational processes to reduce the differences in power that in turn help build a lasting and just peace.

Conclusion

Discussing the concept of peace, in both the negative and positive framings, helps highlight how the decision of what to measure can shape the goals we set as public administrators. The positive peace framing, which emphasizes the importance of a just peace, can push public administrators to look at deeper relational and process indicators like inclusion of diverse voices in a community alongside more easily measured indicators of negative peace.

Author: Grant Rissler is Assistant Professor of Organizational Studies at the School of Professional and Continuing Studies, University of Richmond (VA). He serves on the editorial board of Administrative Theory & Praxis (ATP) and focuses his research on social equity and peacebuilding with particular interest in local government responsiveness to immigrants. The “On My Desk” series of columns, beginning in July 2024, intentionally highlights the insights of one or more articles published in ATP in relation to a current debate or event. Grant can be reached at [email protected].

Follow Us!