Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

On My Desk: Whiteness and Public Administration

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Grant E. Rissler

August 2, 2024

Recent scholarship explores and explains the role of Whiteness in U.S. society and public administration, yielding insights that are increasingly relevant as the U.S. presidential election shifts away from a match up between two white male candidates for only the fourth time in U.S. history.

This fall, something will happen for only the fourth time in 248 years of U.S. history. With U.S. Vice-President Kamala Harris now likely to replace President Joe Biden as the Democratic Party nominee for president in 2024, the two major party nominees will not both be white males for only the 4th time in 60 Presidential elections.

Three recent elections (2008, 2012 and 2016) featured greater diversity too, but the unbroken string of white male-only contests from 1789 to 2004 highlights the reality, obvious when considered but often unremarked upon, that being white and male were long-held or still held de facto requirements for the U.S. Presidency, as well as for a lot of other roles. (For example, according to the Center for American Women in Politics, while a record 12 governor’s seats are held by women, eighteen states have yet to elect a woman as governor. The Center for the American Governor notes that 46 current state governors are white non-Hispanic; only one current governor is Black, the third elected Black male governor in U.S. history, while two are Hispanic and one is Native American.)

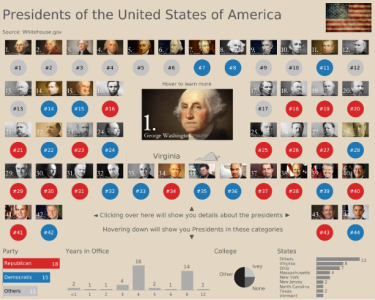

I say that the pattern is often “unremarked” based on my lived experience as a white male that grew up in in a small Virginia county in the 1980’s and early 90’s. (My experience is obviously not universal, but on this count my guess is that it was also not uncommon.) I don’t remember any point during my grade school education where a history teacher pointed to a poster of all the U.S. presidents that had a handy key to show which ones were white males, or that any teacher remarked on the oddity of that fact, given the demographic diversity of the United States. Many who are younger than I have hopefully benefitted from a richer, less white-washed teaching of history. Yet today my quick online search for interactive versions, like the visual below, turn up versions that are very similar to those of my childhood. The visual offers break outs on, among other things, which Presidents attended Ivy League schools, but don’t offer the same for race (44-1) or gender (45-0).

For many reading this column, the pattern is far from being news and U.S. society becomes more racially and ethnically diverse each year. But the pushback against DEI initiatives, as well as the disinformation experienced by Vice-President Harris and others in 2020 and the immediate resurgence of critiques since she became the likely Democratic nominee, point to a continued need to “remark” on the pattern. And such patterns need to remarked upon by whites, within predominantly white spaces, “nervous” as such conversations may be. This is partly about responsibility and not shifting the burden onto people of color. But it is also about the reach of such communications—a 2022 Public Religion Research Institute study of a representative group of 5,000 Americans found that 67 percent of White Americans “list only other white people in their friendship networks—a decrease from 75 percent in 2013.”

Studying Whiteness

Whiteness as a topic of study emerged as an effort to look at patterns around race in white dominated societies that often are not surfaced or discussed—of how being in the category of “white” shapes, benefits or “privileges” the experiences and outcomes of those who adopt that identity, rather than setting up those experiences as the unremarked (and uncritiqued) norm. Moreover, as Love and Stout point out in their article in the special issue highlighted below, this privileged status carries over into the legal system and administrative state and “is enacted as a form of property right, imbued with the claims to state protection, exclusive access and entitlement to profit extracted.”

To give one example of this, Matthew Hughey in Whither Whiteness? The Racial Logics of the Kerner Report and Modern White Space writes that in regards to educational choices for children, whites often expect a right for their children to be culturally comfortable in public schools (but don’t see that same right as applying to non-white children) or they leave those schools, sometimes with a demand to be supported by the state (e.g. vouchers, tax breaks) in doing so. He recounts that, in referring to school desegregation efforts, one white woman told him “that her children would not be ‘used as guinea pigs in some social experiment, even if I agree that’s how things should be’ (human resources manager, age forty- four…).”

A recent special issue of the journal Administrative Theory and Praxis focused on “Whiteness in public administration” serves as a similarly helpful platform for a range of public administration scholars to further examine patterns of Whiteness in Public Administration and help the rest of us reflect more deeply on where we see these patterns playing out around us. The editors, Nuri Heckler and Naomi Nishi, provide the following summary in their introduction to the issue:

“The issue begins with a deep dive into the transmogrification process itself, as Blanco (2024) explores the similarities and differences between the development of Mestizaje identity in Mexico and the theoretical position of Whiteness in the Anglo-American world. This article reveals how the power mechanisms of race operate similarly across geopolitical context, but with important regional differences. After this deep dive into global history by a newer scholar, Love and Stout (2024) contribute a powerful critique that exposes White culture in the “underlying assumptions, values, power dynamics, institutional structures and procedures” (p. 144) of public administration theory and practice, before offering some new tools for “transformational change” (p. 158). Then, Scott and Leach (2024) conduct theoretical research into understanding how to leverage the history of White Supremacy and the White culture it creates to unveil the logics of Whiteness and how those logics undermine current efforts to promote social equity in public administration.

Each of the next three articles in this issue contextualize Whiteness as a theoretical purchase by providing examples of the kinds of phenomena that are revealed by the focus that Du Bois (1920) proposed from his high tower (Ch. 2). Carter and Rose (2024) use Whiteness as a toe hold to improve the relationship between civic recreation groups like rock climbing organizations and the Native land on which they do their work. Sweeting and John Camara (2024) theorize their work disrupting Whiteness and White normativity within academia. Finally, Feit (2024) gives a methodical and theoretically rigorous account of the need for a better understanding of Whiteness in representative bureaucracy studies.”

Relevance to Public Administrators

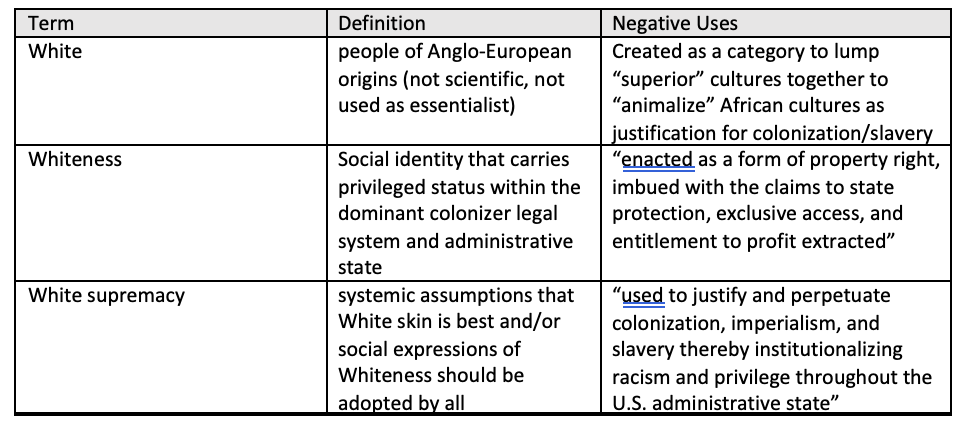

Space is insufficient here to point out the numerous useful contributions across each article, so I will focus, for the time being, on one—Love and Stout’s “Exposing and Dismantling White Culture in Public Administration.” In addition to a cogent summary of the numerous places that evidence exists for disparities “based on Whiteness,” Love and Stout also provide an equally helpful explanation of the key terms of White, Whiteness and White supremacy that are used in their analysis and the key distinctions between them. Table 1 is my effort to pull these key terms out for quick reference, but I encourage readers to engage with the more detailed discussion of these by the authors.

Table 1: Summary of key terms used by Love and Stout in “Exposing and Dismantling White Culture in Public Administration.” Quotes are from 147-148.

Additionally, the authors provide one of the best and succinct discussions of the different types of power (i.e. power-over vs. power-with vs. power within, etc.) that I’ve read and then leverage that into a detailed exploration of how the privileging of Whiteness (underlying Eurocentric cultural preferences and values) and the uses of exploitative “power-over” generate “pathological power dynamics.” For public administrators working to advance equity within institutions that are steeped in and built around hierarchical organizing structures, this discussion of the full range of power types and analysis of how they interact is essential reading.

Likewise, the authors provide a review of each “school” of public administration thought, from orthodox writers of the early 20th Century, through New Public Service and New Public Governance, pointing out both efforts to shift away from some of the worst aspects of those pathological power dynamics, but also where the reformed versions retain significant elements of Whiteness that requires assimilation to those same values to be part of the profession of public administration.

Finally, the authors (page 159-160) offer advice on the need for “systemic transformation,” especially through a shift away from “power-for” strategies and to strategies based on authentic “power-with” collaborations that “foster solidarity while honoring difference” through cultural integration, which “requires all contributing parts to change as a new inclusive whole is developed.” Moreover, they call for public administrators to “turn their gaze away from oppressed communities toward oppressive systems.”

Conclusion

U.S. society is growing increasingly diverse and also continues to be rooted in a long history of exclusionary legal and cultural systems which imbues U.S. culture to this day. Recent scholarship explores and explains the role of Whiteness in U.S. society and public administration, yielding insights that are increasingly relevant as the transformation from a white dominant society continues.

Author: Grant Rissler is Assistant Professor of Organizational Studies at the School of Professional and Continuing Studies, University of Richmond (VA). He serves on the editorial board of Administrative Theory & Praxis (ATP) and focuses his research on social equity and peacebuilding with particular interest in local government responsiveness to immigrants. The “On My Desk” series of columns, beginning in July 2024, intentionally highlights the insights of one or more articles published in ATP in relation to a current debate or event. Grant can be reached at [email protected].

Follow Us!