Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Public Administration, Public Goods and Environmental Rehabilitation

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Tom R. Hulst

March 10, 2025

During this time of contempt for government and disrespect for public administration, it is important to highlight the value of public service and, as emphasized in this article, public goods. Public administrators need to redouble efforts to clarify the value of investment in public goods at every level of government. The public has a skewed view of public goods because they seem opaque, invisible and sometimes wasteful. Public goods are invisible and importantly, indivisible, in the sense that they cannot be divided into smaller units for individual consumption. Classic examples include national defense, museums, airports, roadways, libraries and public parks. Public goods are provided so that they benefit all members of society simultaneously—and equally.

According to economists, the indivisibility of public goods entails two primary characteristics: non-excludability and non-rivalry. Non-excludability means it is not feasible to prevent individuals from using the good once it is provided. Non-rivalry implies that one person’s use of the good does not diminish its availability to others. These characteristics make public goods distinct from private goods, which are both excludable and rivalrous. Public goods by their nature necessitate government intervention to ensure availability and equitable distribution. These attributes mean that public goods are available to all members of society without excluding anyone from their use; and one person’s use of the good does not limit its availability to others.

The indivisibility of public goods highlights the challenges associated with their availability. Public goods are not received through individual transactions in the marketplace and thus are very often taken for granted. Within the economic framework of the United States, people, seem to prefer market driven goods over public goods because they are more apparent, individualized and consumer driven. Many people prefer water in plastic bottles to drinking fountains; hand-held devices over national parks; private automobiles over buses and trains; video games to museums; and private schools over public education. Determining the optimal mix of public goods and funding levels can be complex. Governments must balance the benefits of public goods against the costs of taxation, economic development and potential inefficiencies in public sector production.

One type of public good that should be more clearly communicated to the public—and indeed celebrated—is the rehabilitation of contaminated sites. In 1969 the Cuyahoga River erupted in a fire. Wedged debris beneath the bridges over the river near Republic Steel in Cleveland, Ohio, caused the material to stack up. Oil on the water added to its flammability. A flare likely from an overpassing train provided the spark that ignited the debris. While it was extinguished quickly, the “river fire” symbolized the environmental degradation that had occurred throughout the country. Together with the oil spill near Santa Barbara in 1969 the Cuyahoga River fire mobilized the public about the needs of environmental protection that in turn resulted in the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970. Subsequently, in 1980 the Superfund program, officially known as the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA), was enacted by Congress to clean up the nation’s most contaminated property.

The impact of the Superfund program has led to the cleanup of thousands of dangerous waste sites across the United States and reduced the exposure to harmful substances. The program has also revived communities by transforming spoliated sites into usable public goods: land for parks, schools and other public places. Between 2014 and 2024, the EPA allocated substantial resources to the Superfund program to clean up pollution across the United States. The EPA’s budget for Superfund activities ranged from $8 billion to $10 billion annually over the past decade. This funding was used to clean up some of the nation’s most contaminated lands, protect public health and support community re-building efforts. A map showing Superfund sites in each state is provided here. https://www.epa.gov/superfund/search-superfund-sites-where-you-live#map.

In 1974, President Ford signed legislation to create Cuyahoga Valley National Park a few miles upstream from the fire location. The park protects 22 miles of river, nearly a quarter of its length. Today, the National Park Service and its partners restore habitats that protect the river. Wetlands and forest are priorities—with over 1,500 wetlands occurring in the park. Forests shade waterways preventing overheating, and trees at the water’s edge extend their roots to stabilize the riverbanks.

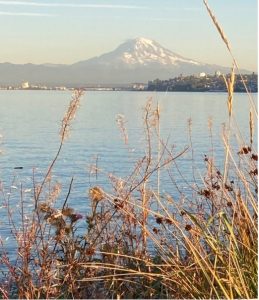

Similarly, across the country in Tacoma, Washington, at another Superfund site, the Dune Peninsula Park was built on the ruins of an historic lead-and-copper smelter. State agencies, City of Tacoma and Metropolitan Parks shared the $74.8 million clean-up cost with the Environmental Protection Agency. Beginning in 2016, 400,000 cubic yards of dirt were moved, and native drought-resistant shrubs were planted. Today, people walk and picnic along the water, while children climb the mounds. Harbor seals repose on rocks offshore and a kelp forest blooms in the sound.

These projects are striking examples of the importance of public goods that exist throughout the country today. The public administration community can help communicate these success stories so generations of Americans can better understand the importance of investment in public goods that last several lifetimes and help preserve the planet.

Author: Tom R. Hulst received an MA in public administration from Washington State University. He served as policy advisor to Washington Governor Daniel J. Evans, administrator in the State Superintendent Office of Public Instruction, and superintendent of Peninsula School District. He wrote “The Footpaths of Justice William O. Douglas” in 2004 and currently teaches political science at Tacoma Community College.

Joan Harvey Nelson

March 13, 2025 at 5:55 pm

What a wonderful summary of the Superfund program with maps that help show the vast scope of what’s been accomplished. The Tacoma superfund site Hulst commented on addressed a serious health hazzard from a copper smelter and provided land for Point Ruston development of housing, shops, restaurants, a hotel, movie theater and more along Puget Sound in Tacoma with a wonderful public area with fountains the children from all over Tacoma love to splash in.