Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Understanding the Current Crisis in Public Administration: Part 2 – Economics Matters

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Erik Devereux

June 27, 2025

This is the second column in a series on the current crisis in American public administration that feels at the moment like a magnitude 9.2 earthquake in the Los Angeles basin. The first column in the series invoked plate tectonics as a metaphor for thinking about what has transpired with the federal government since January 20. What matters most are the subterranean forces slowly building up immense pressures which ultimately are expressed in seemingly rapid shifts in the public landscape. One of those forces, and perhaps the primary one, is economics and more specifically, trends in economic conditions within the U.S. that ultimately are expressed in politics.

Twelve years ago, French economist Thomas Piketty published one of the most important treatises that pertain to current events, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Piketty’s central claim is that 400 years of data show how capitalism has an inherent tendency toward income and wealth inequality. The only period in the data that goes against this tendency is the 20 to 30 years after World War Two (1945–1970 or so). During that period, unskilled and semi-skilled workers in the U.S. achieved considerable growth in real wages and became upwardly mobile members of a burgeoning “blue collar” middle class. Many of those workers also were reliable voters for the Democratic Party and thus supported the expansion of the administrative state through such programs as Medicare, Medicaid and AFDC. But after 1970–75, wages stagnated, the employment market transformed to offer minimum wage jobs to unskilled and semi-skilled workers and the brief intermission in the longer tendency toward economic inequality ended.

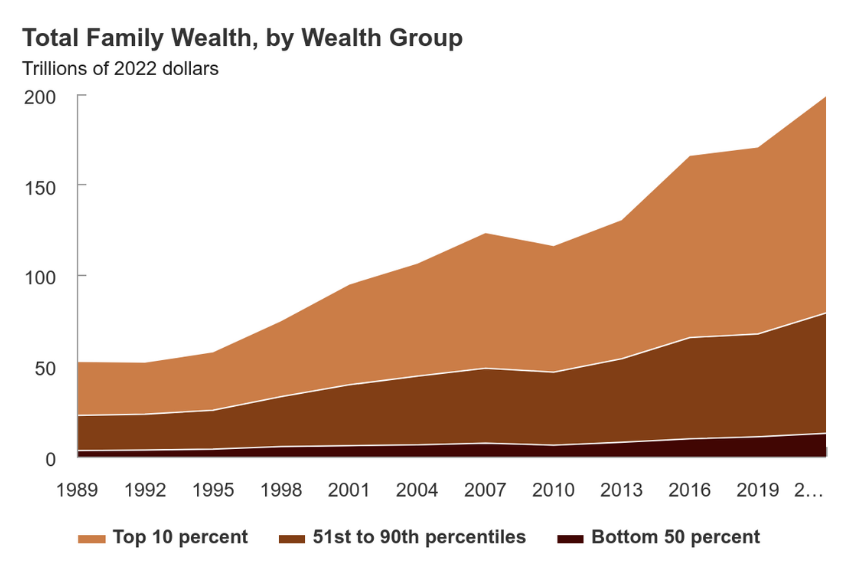

The result is well known. As illustrated in the graphic from the U.S. Congressional Budget Office at the top of this column, the U.S. has seen accelerated wealth inequality ever since. Currently, just 1 percent of U.S. families control over 30% percent of all wealth in the country.

American economics shifted back toward the longer term trend observed by Piketty during the period of “stagflation” 1977–1983. Paul Volcker, then Chair of the Federal Reserve, testified before the Congress in 1979 that Americans on average were experiencing a lower standard of living for the first time in a generation. After stepping down from the Federal Reserve, Volcker later observed that the eventual economic recovery of Europe and Asia after World War Two meant that it was impossible to prevent a gradual decline in the U.S. standard of living. Underlying this process was a vision among economic leaders that the U.S. standard of living eventually needed to “equilibrate” with the global standard. Volcker went on to say that the role of the Federal Reserve was to minimize the domestic “earthquakes” likely to result. What seems to have occurred instead is that the ensuing pressures within the political system accumulated to contribute to the current moment.

Two interacting processes are at work here. On the one hand, the U.S. political system has proven to be highly influenced by the preferences of the wealthy. One consequence is decades of efforts to relieve the wealthy of their tax burdens (I previously discussed this in the PA Times here and here). As wealth inequality accelerated, so did the political influence of the wealthy on tax policy. On the other hand, unskilled and semi-skilled workers became increasingly dissatisfied with their personal economic situations. These voters began shifting away from the Democrats toward the Republicans. At the same time that the federal government lost tax revenue and the federal debt grew rapidly, the American electorate began supporting politicians inclined to offer tax cuts to the wealthy and roll back the administrative state.

When I was taking graduate courses in political economy at MIT and the University of Texas, much of the literature was focused on the positive linkages between capitalism and democracy. One prominent argument was that capitalism requires democracy to thrive. Today it seems more likely that unregulated capitalism is incompatible with democracy. Paradoxically, what is required for capitalism and democracy to co-exist is a strong administrative state capable of enforcing progressive taxation and deploying government resources to mitigate the consequences of global economic change for American workers. Tearing down the administrative state is a prescription for accelerating the forces that will undermine democracy.

Piketty’s prescription for stabilizing democracy is to achieve enforced progressive taxation. Many other prominent voices are calling for the same. Unfortunately, the current trends are indicative of those powerful subterranean forces. The jury is out on whether experts or anyone else can reverse the push for even more tax cuts for the wealthy in an era of extreme wealth inequality.

Economic change since World War Two is just one of the inexorable forces that have accumulated to undermine support for a strong American administrative state. But other forces also have contributed to our current politics. These include demographics, immigration and the apparent inevitable arc of empire. The future columns in this series will examine how economics has interacted with these other forces to reinforce the attack on the federal bureaucracy.

Author: Erik Devereux is Teaching Associate Professor in the Department of Public Policy, Management and Analytics at the University of Illinois-Chicago. He has a B.S. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Political Science, 1985) and a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin (Government, 1993). He is the author of Methods of Policy Analysis: Creating, Deploying and Assessing Theories of Change (available for free here). Email: [email protected]. More content is available here.

Follow Us!