Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

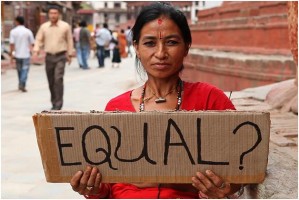

The 21st Century Worker: Beyond Genderization of Reproductive and Productive Roles

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Sunday Olukoju

June 23, 2015

Defining public policy, the Washington, D.C. based International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) posits that “At the simplest level, policies include laws, local policies and government plans, resource allocation plans, regulatory measures and funding priorities that are promoted by a governmental body.” From this definition, public policy seeks the best interest of everyone.

For the 21st century worker, public policy must address genderization of reproductive and productive roles. The idea that a particular gender’s role is strictly reproductive and care giving, while another gender sees engagement in productive activity as sole prerogative should be corrected.

Curiously, ICRW opines that “At some level, policies enshrine societal values and norms as well as regulate daily life and individual practices,” while “Policies can also be the absence of a law or regulation.” When certain issues are omitted from a stated policy, the omission could be considered a form of policy. A few questions arise:

- At what point is a public policy counterproductive?

- At what point does the omission of certain issues in a policy become THE policy? Who determines this?

- Who determines societal values and norms enshrined in the policy (which now dictates individual practices)?

Genderization and Public Policy

According to ICRW, individual policymakers (male or female) view the world through the lens of their own attitudes about what it means to be a man and woman. From international passports to job placement application forms at the local grocery stores, there is often a question about gender. Has anyone ever asked: Why?

According to ICRW, individual policymakers (male or female) view the world through the lens of their own attitudes about what it means to be a man and woman. From international passports to job placement application forms at the local grocery stores, there is often a question about gender. Has anyone ever asked: Why?

ICRW believes those who implement policies and public services in a gendered world—citing the example of how policy views reproductive roles as mostly women’s work and productive roles as being mostly the sphere of men—tend to view the world narrowly.

In assessing the earning disparities between men and women in the U.S. between 1970 and 2010, “Working hours have become the most dominant factor accounting for the gender pay gap, followed by occupational segregation,” according to Hadas Mandel and Moshe Semyonov, in a 2014 Demography Journal article titled “Gender Pay Gap and Employment Sector: Sources of Earnings Disparities in the United States, 1970-2010.”

Women, though highly educated, are drawn more to fields of education, administration and social sciences. There are fewer women in engineering and technical fields, inadvertently leading to gender occupational segregation. With the occupational culture that demands overtime and odd-hour work, many women find it difficult to meet the domestic division of labor at home. This, some argue, gives men an edge in the job market.

Beyond Genderization of Reproductive and Productive Roles

Using the ICRW approach, policy and decision makers should be mandated to:

(1) Adopt a human rights approach in creating comprehensive policy initiatives that would degenderize the strict allocation of reproductive and productive roles, while promoting one that could allow fathers and husbands to stay home and nurture a child while the mother returns to work early.

(2) Develop measurable indicators and outcomes that are both qualitative and quantitative in ensuring that men and women are trained and fairly distributed across professional fields.

(3) Create alternative opportunities like ‘take-home’ assignments for women who are unable to work odd hours.

(4) Initiate income support and livelihood policies, employment promotion, job flexibility and conditional cash transfer initiatives along with other social development and welfare policies especially for vulnerable employees, regardless of gender.

(5) Regular update of policies to promote family life, including joint custody laws, maternity/paternity leave and encourage male participation as fathers and caregivers.

(6) Update policies on health, including general health promotion, sexual and reproductive health, HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment and youth and adolescent health with emphasis on collective responsibility.

(7) Promote education, including policies to promote gender equity.

(8) Strengthen violence prevention policies, including gender-based violence prevention, sexual exploitation and trafficking and violence against children, adolescents and the elderly.

(9) Develop public security policies, especially those that relate to armed forces, police and incarceration with a recruitment policy that promotes fair representation of the population across gender lines.

Also, incentives should go toward encouraging more women in engineering and technical field. Doing so would stem the unequal distribution of men and women across these occupations which have led to gendered division of labor. Such incentives would help eliminate the domestic division of labor that created a barrier to overtime work.

Author: Sunday Akin Olukoju, Ph.D. is the president of Canadian Center for Global Studies, a nonprofit organization and also teaches at Athabasca University in Alberta, Canada. Olukoju can be reached at [email protected].

Follow Us!