Bags Packed? Public Service Empowerment after Disaster

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Anthony Buller

January 12, 2018

They are everywhere. I keep running into them–these people who deployed in support of the 2017 hurricane season. They come from different agencies, different homes and have different careers and skills. A lot of the people I meet now are at the federal level, but it sure isn’t just the federal level. States and territories supported states and territories. Voluntary organizations, the private sector–you name it and we can find examples. All sorts of different people traveled to Texas, Louisiana, Florida, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and many other jurisdictions to help.

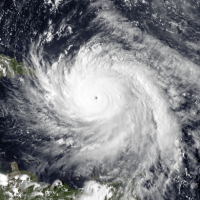

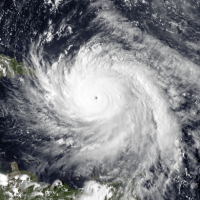

Harvey, Irma, Maria – 2017 was certainly another unique hurricane season. I started in emergency  management in 2004 and then the names were Charley, Frances, Ivan and Jeanne. That year is sort of lost on some people considering that in 2005 we faced Dennis, Katrina, Rita and Wilma. Major hurricanes often top our minds but there was Superstorm Sandy, and don’t think lower category hurricanes or even tropical storms are jokes: they matter too. From the tip of Texas to the top of Maine, the U.S. territories in the Caribbean, to Hawaii and the U.S. territories out in the Pacific, storm names mean something: They take lives, and they change lives.

management in 2004 and then the names were Charley, Frances, Ivan and Jeanne. That year is sort of lost on some people considering that in 2005 we faced Dennis, Katrina, Rita and Wilma. Major hurricanes often top our minds but there was Superstorm Sandy, and don’t think lower category hurricanes or even tropical storms are jokes: they matter too. From the tip of Texas to the top of Maine, the U.S. territories in the Caribbean, to Hawaii and the U.S. territories out in the Pacific, storm names mean something: They take lives, and they change lives.

When you tally the figures, you can see that more than 100,000 people traveled (and continue to travel) to states and territories impacted by this past hurricane season. They work for governments at all levels. They work for business. And many are actual unpaid volunteers. They responded. And often, and importantly, they were empowered to respond.

Consider that every public servant who traveled to help was presumably authorized to do so by their leadership. Public administrators at all levels allowed, equipped and perhaps even encouraged the service. The people who went certainly deserve a lot of thanks, but so do those who authorized it. So, if you sent people to serve: thank you.

This column is about the question: why? Why do public administrators send their people to help after a disaster? Or better…

Why do we (or should you) empower people to serve after disaster?

#1 Support the mission of your organization

Perhaps the most obvious answer: some agencies are committed to certain roles after disaster. Right now, the US Army Corps of Engineers is restoring power in Puerto Rico. Why them? Well, the National Response Framework (NRF) says so. Emergency management has established Emergency Support Functions (ESFs), which organize responders into 15 categories (though ESF14 is reserved at this time). So, if your agency or organization works in transportation you connect to ESF1: Transportation. Health and Medical Services? That’s ESF8. The ESFs are a national system, which means more than just federal. The vast majority of states and local governments organize via the ESFs. Speaking of states, state emergency managers work hard with other state agencies to equip them to perform their roles on disaster. But when the disasters grow larger, more partners may need to plug in. Out-of-state support comes in a couple ways, but often it comes through the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) process. One jurisdiction puts in a request and another with that resource (including people with the right skills) fills the request.

#2 Increase the readiness and capability of your own organization

More than just practicing for a role, the staff development during the deployment returns investment to your organization. The lessons they’ve learned on someone else’s disaster can equip your own agency. I know an example of state staff deploying from one coast to another to help run an animal shelter. That staff returned to their own state and within six months the state had their own pet sheltering plan and capability.

#3 Invigorate motivation and a public-service value

The least tangible, but the most easily felt, benefit accrues to those who deploy in service to those in need. You can gain (or regain) a sense of meaning. A lot of meaning can come from serving survivors and their communities after disaster. Those that do are often more aware of the importance of public service. The role on the disaster deployment might be wholly unrelated to the day-to-day job too. I recently met a Transportation Security Administration (TSA) employee who naturally works in security. But in Florida last year he supported Disaster Recovery Centers (DRCs) where survivors can go to receive multi-agency assistance. The experience was powerful for him.

As public administrators we should empower our staff to help on disaster. By the number of people I met from all walks who went to help in 2017, I’d say many public leaders do so. For those who don’t, please consider it. Or go yourself if you can. It might change your life. It did mine in 2004.

Author: Anthony Buller has deployed to 40 presidentially declared major disasters and emergencies in his 13 years of federal service. He now leads a team of security and emergency management professionals in Denver, CO. He can be reached at: [email protected].

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

Loading...

Loading...

Bags Packed? Public Service Empowerment after Disaster

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Anthony Buller

January 12, 2018

They are everywhere. I keep running into them–these people who deployed in support of the 2017 hurricane season. They come from different agencies, different homes and have different careers and skills. A lot of the people I meet now are at the federal level, but it sure isn’t just the federal level. States and territories supported states and territories. Voluntary organizations, the private sector–you name it and we can find examples. All sorts of different people traveled to Texas, Louisiana, Florida, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and many other jurisdictions to help.

Harvey, Irma, Maria – 2017 was certainly another unique hurricane season. I started in emergency management in 2004 and then the names were Charley, Frances, Ivan and Jeanne. That year is sort of lost on some people considering that in 2005 we faced Dennis, Katrina, Rita and Wilma. Major hurricanes often top our minds but there was Superstorm Sandy, and don’t think lower category hurricanes or even tropical storms are jokes: they matter too. From the tip of Texas to the top of Maine, the U.S. territories in the Caribbean, to Hawaii and the U.S. territories out in the Pacific, storm names mean something: They take lives, and they change lives.

management in 2004 and then the names were Charley, Frances, Ivan and Jeanne. That year is sort of lost on some people considering that in 2005 we faced Dennis, Katrina, Rita and Wilma. Major hurricanes often top our minds but there was Superstorm Sandy, and don’t think lower category hurricanes or even tropical storms are jokes: they matter too. From the tip of Texas to the top of Maine, the U.S. territories in the Caribbean, to Hawaii and the U.S. territories out in the Pacific, storm names mean something: They take lives, and they change lives.

When you tally the figures, you can see that more than 100,000 people traveled (and continue to travel) to states and territories impacted by this past hurricane season. They work for governments at all levels. They work for business. And many are actual unpaid volunteers. They responded. And often, and importantly, they were empowered to respond.

Consider that every public servant who traveled to help was presumably authorized to do so by their leadership. Public administrators at all levels allowed, equipped and perhaps even encouraged the service. The people who went certainly deserve a lot of thanks, but so do those who authorized it. So, if you sent people to serve: thank you.

This column is about the question: why? Why do public administrators send their people to help after a disaster? Or better…

Why do we (or should you) empower people to serve after disaster?

#1 Support the mission of your organization

Perhaps the most obvious answer: some agencies are committed to certain roles after disaster. Right now, the US Army Corps of Engineers is restoring power in Puerto Rico. Why them? Well, the National Response Framework (NRF) says so. Emergency management has established Emergency Support Functions (ESFs), which organize responders into 15 categories (though ESF14 is reserved at this time). So, if your agency or organization works in transportation you connect to ESF1: Transportation. Health and Medical Services? That’s ESF8. The ESFs are a national system, which means more than just federal. The vast majority of states and local governments organize via the ESFs. Speaking of states, state emergency managers work hard with other state agencies to equip them to perform their roles on disaster. But when the disasters grow larger, more partners may need to plug in. Out-of-state support comes in a couple ways, but often it comes through the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) process. One jurisdiction puts in a request and another with that resource (including people with the right skills) fills the request.

#2 Increase the readiness and capability of your own organization

More than just practicing for a role, the staff development during the deployment returns investment to your organization. The lessons they’ve learned on someone else’s disaster can equip your own agency. I know an example of state staff deploying from one coast to another to help run an animal shelter. That staff returned to their own state and within six months the state had their own pet sheltering plan and capability.

#3 Invigorate motivation and a public-service value

The least tangible, but the most easily felt, benefit accrues to those who deploy in service to those in need. You can gain (or regain) a sense of meaning. A lot of meaning can come from serving survivors and their communities after disaster. Those that do are often more aware of the importance of public service. The role on the disaster deployment might be wholly unrelated to the day-to-day job too. I recently met a Transportation Security Administration (TSA) employee who naturally works in security. But in Florida last year he supported Disaster Recovery Centers (DRCs) where survivors can go to receive multi-agency assistance. The experience was powerful for him.

As public administrators we should empower our staff to help on disaster. By the number of people I met from all walks who went to help in 2017, I’d say many public leaders do so. For those who don’t, please consider it. Or go yourself if you can. It might change your life. It did mine in 2004.

Author: Anthony Buller has deployed to 40 presidentially declared major disasters and emergencies in his 13 years of federal service. He now leads a team of security and emergency management professionals in Denver, CO. He can be reached at: [email protected].

Follow Us!