Balancing the Scales: Critiquing Gender Equity Research in the American Legal Field

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Nicholas Mastron

March 26, 2018

As March celebrates women’s global contributions and achievements personally and professionally, the legal and economic statuses of women remain in public policy foci. Yet, for the women responsible for balancing and upholding the scales of American justice, pay equity appears stagnated and unresponsive in private and nonprofit settings.

Despite many pro-women advancement policies, female attorneys have largely seen no statistically significant shifts in narrowing the pay gap in the past two decades. Contrary to increasingly high labor force participation, evidence exists that pay disparity trends have actually remained virtually constant since the 1950s and 1960s.

However, the legal field’s pay disparities possess both unique cultural elements due to its litigious settings and common measurement pitfalls shared by other fields that are just less obscured in the private legal environment. These facets constitute many of the often-cited issues with even constructing and defending the notion of a gender pay gap.

The Industry-Occupation Problem

Pay equity analyses showing substantial gaps rarely control beyond the sex of workers, but the legal field constitutes a field more than an industry. As such, using industry and occupation variables might add little to no explanation about the economic equities of men and women practicing law.

On the one hand, reluctance to include many industry characteristics threatens the analysis to critical undermining and suggests an over-exaggerated gap. A recent Glassdoor.com study highlights this ability to potentially “explain away” many of the disparities in industry pay gaps.

Yet, upon closer inspection, inclusion of industry variables may undermine the statistical conclusion validity of the research question regarding the legal field. Pay equity studies incorporating both industry and occupation variables yield different correlations depending on the industry, potentially amplifying the effect those included controls would have on the pay gap. What this implies is that researchers should better determine whether to include occupation, industry, or both variables depending on the type of work or service.

While considered to be an industry of professional employment by the U.S. Department of Labor, the legal field actually functions as semi-independent guilds of legal practitioners because those legally trained workers are united by craft, not company or industry. So, industry variables particularly should be avoided in wage analyses for lawyers, and the occupation variable already constitutes a control in performing this analysis.

Moreover, the noted variances associated with legal workers electing different industries in which to practice law ignore human capital and labor progression factors that better explain these industry differences than merely controlling for industry in these studies.

The Human Capital Problem

Most equity analyses include some human capital elements, chiefly education and skills variables, whether they serve as controls, parameters, or even lag effects. Yet, legal field equity analyses often misappropriate these elements in the equation with respect to its own restrictions and settings by using traditional control settings, like years of education, law school performance or skills acquisition.

Almost all state bar associations mandate three-years’ (or four-years’ for part-time attendees) curriculum in terms of legal education. While seven states provide exceptions to avoid this legal education, thereby supporting this variable’s inclusion, so few workers pass those alternative requirements that the point remains moot (only 17 individuals in 2015). Thus, the relevance of years of education as a variable is limited due to the nearly universal acquisition of three to four years of post-baccalaureate education.

Regarding law school performance, little to no evidence exists to connect this variable to post-school abilities; similarly, once a legal worker is barred and begins practicing, the skills components, also remain fairly constant (usually 12-15 hours annually) across states’ jurisdictions. While the offered Continuing Legal Education (CLE) credits widely vary, these additional skills cannot function as controls under the original question but can distill what type of gender gap among attorneys exists.

Within these human capital concerns, gender pay equity studies should seek less to utilize these elements as controls but as assumed constants which may suggest alternative policy actions.

The Labor Progression Problem

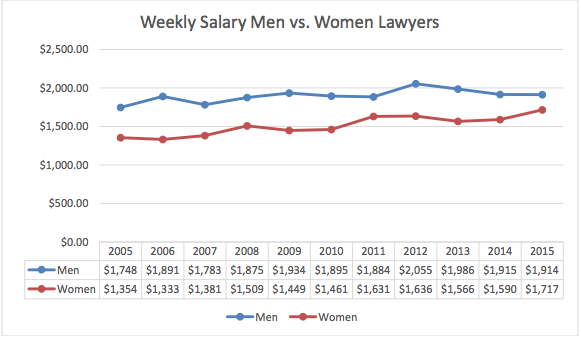

However, the most egregious and widespread measurement error in the gender pay gap for attorneys remains ignorance of lagged effects regarding tenure at a place of employment. Recent evidence suggests that failure to account for these effects drives the gap to appear quite narrow, as in the chart above.

In terms of pay disparities at entry, the legal field appears as one of the most egalitarian fields both in terms of labor force participation and pay equity among the sexes. Yet, in climbing a firm’s corporate ladder, women only constitute a fifth of all equity partners.

This starker but delayed pay disparity evidences the higher attrition rates for female attorneys due to firm economics and cultures. Known contributing factors to this attrition include billing and compensation requirements, general promotion awards, and provided client engagement. Hidden by the vast supply of young lawyers that enter the legal field initially, this larger lagged attrition, driving a higher pay gap in reality, deserves greater attention than merely the occupation-sex intersectional study that research traditionally observes.

Author: Nicholas Mastron is a current doctoral student in Public Policy & Administration at the George Washington University, with a field specialization in Social & Gender Policy. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him @NicholasMastron.

(2 votes, average: 4.50 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 4.50 out of 5)

Loading...

Loading...

Balancing the Scales: Critiquing Gender Equity Research in the American Legal Field

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Nicholas Mastron

March 26, 2018

As March celebrates women’s global contributions and achievements personally and professionally, the legal and economic statuses of women remain in public policy foci. Yet, for the women responsible for balancing and upholding the scales of American justice, pay equity appears stagnated and unresponsive in private and nonprofit settings.

Despite many pro-women advancement policies, female attorneys have largely seen no statistically significant shifts in narrowing the pay gap in the past two decades. Contrary to increasingly high labor force participation, evidence exists that pay disparity trends have actually remained virtually constant since the 1950s and 1960s.

However, the legal field’s pay disparities possess both unique cultural elements due to its litigious settings and common measurement pitfalls shared by other fields that are just less obscured in the private legal environment. These facets constitute many of the often-cited issues with even constructing and defending the notion of a gender pay gap.

The Industry-Occupation Problem

Pay equity analyses showing substantial gaps rarely control beyond the sex of workers, but the legal field constitutes a field more than an industry. As such, using industry and occupation variables might add little to no explanation about the economic equities of men and women practicing law.

On the one hand, reluctance to include many industry characteristics threatens the analysis to critical undermining and suggests an over-exaggerated gap. A recent Glassdoor.com study highlights this ability to potentially “explain away” many of the disparities in industry pay gaps.

Yet, upon closer inspection, inclusion of industry variables may undermine the statistical conclusion validity of the research question regarding the legal field. Pay equity studies incorporating both industry and occupation variables yield different correlations depending on the industry, potentially amplifying the effect those included controls would have on the pay gap. What this implies is that researchers should better determine whether to include occupation, industry, or both variables depending on the type of work or service.

While considered to be an industry of professional employment by the U.S. Department of Labor, the legal field actually functions as semi-independent guilds of legal practitioners because those legally trained workers are united by craft, not company or industry. So, industry variables particularly should be avoided in wage analyses for lawyers, and the occupation variable already constitutes a control in performing this analysis.

Moreover, the noted variances associated with legal workers electing different industries in which to practice law ignore human capital and labor progression factors that better explain these industry differences than merely controlling for industry in these studies.

The Human Capital Problem

Most equity analyses include some human capital elements, chiefly education and skills variables, whether they serve as controls, parameters, or even lag effects. Yet, legal field equity analyses often misappropriate these elements in the equation with respect to its own restrictions and settings by using traditional control settings, like years of education, law school performance or skills acquisition.

Almost all state bar associations mandate three-years’ (or four-years’ for part-time attendees) curriculum in terms of legal education. While seven states provide exceptions to avoid this legal education, thereby supporting this variable’s inclusion, so few workers pass those alternative requirements that the point remains moot (only 17 individuals in 2015). Thus, the relevance of years of education as a variable is limited due to the nearly universal acquisition of three to four years of post-baccalaureate education.

Regarding law school performance, little to no evidence exists to connect this variable to post-school abilities; similarly, once a legal worker is barred and begins practicing, the skills components, also remain fairly constant (usually 12-15 hours annually) across states’ jurisdictions. While the offered Continuing Legal Education (CLE) credits widely vary, these additional skills cannot function as controls under the original question but can distill what type of gender gap among attorneys exists.

Within these human capital concerns, gender pay equity studies should seek less to utilize these elements as controls but as assumed constants which may suggest alternative policy actions.

The Labor Progression Problem

However, the most egregious and widespread measurement error in the gender pay gap for attorneys remains ignorance of lagged effects regarding tenure at a place of employment. Recent evidence suggests that failure to account for these effects drives the gap to appear quite narrow, as in the chart above.

In terms of pay disparities at entry, the legal field appears as one of the most egalitarian fields both in terms of labor force participation and pay equity among the sexes. Yet, in climbing a firm’s corporate ladder, women only constitute a fifth of all equity partners.

This starker but delayed pay disparity evidences the higher attrition rates for female attorneys due to firm economics and cultures. Known contributing factors to this attrition include billing and compensation requirements, general promotion awards, and provided client engagement. Hidden by the vast supply of young lawyers that enter the legal field initially, this larger lagged attrition, driving a higher pay gap in reality, deserves greater attention than merely the occupation-sex intersectional study that research traditionally observes.

Author: Nicholas Mastron is a current doctoral student in Public Policy & Administration at the George Washington University, with a field specialization in Social & Gender Policy. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him @NicholasMastron.

Follow Us!