Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Community Development and the Rural-Urban Divide

A note for our readers: the views reflected by the authors do not reflect the views of ASPA.

By William Hatcher

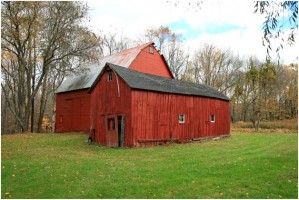

The cultural, natural and environment assets of rural America have been and are a significant part of the nation’s identity. However, over the past century, a divide has grown between rural and urban America. With the current transition of the nation’s economy into a creative class, rural communities have a host of new challenges that may make this divide even more pronounced.

The cultural, natural and environment assets of rural America have been and are a significant part of the nation’s identity. However, over the past century, a divide has grown between rural and urban America. With the current transition of the nation’s economy into a creative class, rural communities have a host of new challenges that may make this divide even more pronounced.

In its latest issue, Governing has a series of articles on issues involving the rural and urban divide in this nation. Article in this series examine the problems of rural health care, the need for rural cities and counties to coordinate and the resilience of rural political power. Public administration and community development need to assist rural communities by giving sound advice in the designing of innovative administrative solutions that can help cities and counties pool resources and properly execute political power for policies based in the modern economy.

Consolidation, Cooperation, and Coordination

One administrative design, which isn’t that new or innovative but is highly effective, is for rural cities and counties to pool their resources. This is already occurring in many areas of public policy. Rural communities may combine resources to fund community health institutions. However, in many areas of governance, there are too many local government units, leading to ineffective public policy. Combining resources is difficult for local governments. The structure of the overall system often forces cities and counties to compete for finite resources—as James Madison wrote in Federalist Paper 10, “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” However, at the end of the day, these numerous units need to govern and their separated nature makes this difficult.

This is not an argument for complete consolidation of rural cities and counties. Over the nation’s history, only a small number of cities and counties (around 40) have consolidated. Georgia has by far the most consolidated local governments, with Bibb County and Macon being the latest examples. In many states, there are legal hurdles that make consolidation difficult if not impossible. And in all communities, consolidation is a very rare event because it is so politically difficult. Local officials are worried about losing their positions and influence. Furthermore, the limited research on consolidated governments has not produced convincing evidence that these arrangements are more efficient and effective than separated local governments. For instance, Edward J. Jepson, in an article in Planning Practice & Research, compared consolidated communities to similar ones that are not consolidated. He found little administrative difference between consolidated communities and non-consolidated ones. Among the cities in his study, consolidation did not produce more cost-efficient policy outcomes for the communities.

Perhaps targeted-coordination and encouraged-cooperation may be the best solutions for local governments to pool their resources. My colleague Dr. Matthew Howell and I have argued that community cooperation is a vital part of development. A pooling of resources in the form of local service agreements may help address many issues facing rural areas.

Resilient Political Power

Even with declining economic influence, rural communities have managed to retain a great deal of political power. Structural features of our political system, such as equal representation in the U.S. Senate and the Electoral College, reinforce political power in rural areas. The Republican Party’s leadership is largely pulled from rural communities. Even with the disjointed nature of American federalism that gives us over 87,000 local government units, rural America has maintained this political power. But many rural communities are using their political power to support policies that try to return them to the nation’s old economy.

Rural communities are using political power to engage in smokestack chasing economic development. Rural areas advocate and secure tax incentives for companies to either stay within their boundaries or relocate to them. Often these companies don’t relocate to rural communities because there are concerns about quality of infrastructure and the local workforce. As I’ve discussed in an earlier column, communities give away their local tax bases with these attraction-based tax incentives. These are valuable public resources that would most likely be better spent on investments in infrastructure and workforce. The manufacturing jobs that these communities wish to attract are no longer a strong part of the nation’s economy.

A Future for Rural America

Since the 1970s, the nation’s working class jobs, in particular manufacturing ones, have declined significantly. This economic trend has hollowed out many of our rural communities. Tax incentive packages and other attract-based policies will not change the power of this economic force. Rural communities should use their political power to advocate for innovative solutions to address health care weaknesses, a lack of cooperation and overall economic development. If rural communities focus on their assets and realistic visions that take into account the fact that these areas may be smaller in economic power and numbers, then there is a sustainable future. Rural areas have a great deal of amenities to attract creative workers. Research has shown that creative class workers are moving to rural areas to take advantage of these amenities. To attract creative class, rural areas need to invest in technology, such as broadband, access to allow for telecommuting; protect amenities, in particular natural amenities and environmental resources; and craft and market a clear vision.

Author: William Hatcher, Ph.D. is an associate professor in the Department of Government at Eastern Kentucky University. He can be contacted via [email protected]. (His opinions are his own and do not necessarily represent those of his employer.)

(2 votes, average: 3.50 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 3.50 out of 5)

Follow Us!