Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Do United States Schools of Public Policy Have the Discipline to Grow a Discipline?

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Erik Devereux

April 27, 2020

This is the second of four columns I will write in 2020 about the current state of United States schools of public policy (You can find the first column here). The motivation for these columns is the ongoing lack of brand recognition for the schools and their flagship degrees among the general public and within the landscape of higher education. There are many explanations for why this obscurity happened; here I will focus on the outsized role of microeconomists in shaping the faculty and curriculum.

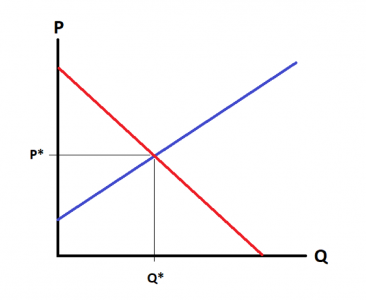

Do not get me wrong: I believe microeconomics is an important skill in the policy analysis toolkit. My textbook (referenced in the bio below) devotes two of its 13 chapters to the subject and urges students to learn benefit-cost. That said, trying to build a brand identity for policy schools around microeconomics proved a mistake.

Looking back at the period 1960–1980 when stand-alone public policy schools began to emerge in the United States and pursue a separate identity from public administration, there was a nascent, separate discipline of public policy analysis emerging from several sources connected to such fields as operations research and decision analysis. This discipline might draw from microeconomics and from several other fields as appropriate, but its analytical core remained distinctly focused on understanding the public policy process using what nowadays often is labeled as sequence analysis.

To build the necessary faculty expertise in the emerging discipline of public policy analysis, several of the founding schools in the field began offering their own Ph.D programs. I have had the good fortune to learn much about the early vision for the discipline from the first graduates of these programs. Why that vision fell short is a story of perverse academic incentives intersected with the exalted position of economics within the social sciences.

The policy school deans charged with building faculty for their schools in the 1970s found that the easiest road to prominence in academe was to hire economists. There were far more economists available than there were Ph.Ds in public policy, and the Ph.Ds in public policy did not bring the instant caché that a “big” economics hire did. Very quickly, the public policy schools began framing their teaching and research mission around applied microeconomics and its kissing cousin, econometrics.

This process went fully public at the seminal 1978 Hilton Head conference on the policy curriculum. For those reading this column who have never heard of it, Hilton Head is where the policy schools came together with funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation to envision the scaffolding for the emerging field. Here are three offspring of Hilton Head: the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management (APPAM, born 1979), which would provide an annual research conference, the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management (JPAM, born 1981), which would provide a publication outlet for the research, and the Public Policy and International Affairs Program (PPIA, born as the Sloan Fellows Program in 1981), which would become a significant diversity initiative for the field.

Hilton Head is where the microeconomists loudly announced that public policy analysis was the same as applied economics. That claim became enshrined in curriculum designs for the MPP and in many of the leading textbooks of the day. It took a few decades to percolate through APPAM and JPAM to the point that APPAM’s annual conference often is treated by attendees as the warm up act for the American Economic Association conference and JPAM articles often read like those in any 2nd tier applied microeconomics journal. There is nothing especially unique or independent; APPAM and JPAM live in the long shadow cast by the economists.

One straightforward measure of how aligning with economics limited the potential of the public policy schools is the academic market for Ph.Ds in public policy. A newly minted Ph.D in economics has a decent chance of getting hired by a public policy school. Despite the current primacy of microeconomics and econometrics in the curriculum, a newly minted Ph.D in public policy has close to zero chance of getting hired by an economics department. While aligning with economics was one path to building a public policy school, it also was a path to permanent second class citizenship.

The question I put to the public policy schools in 2020 is do they have the discipline now to develop their own discipline? The elements of that discipline remain available for consideration. After 50 years of trying the alternative, and reaping its limited rewards, now is a good time to learn from Einstein’s definition of insanity. A lot of luck is about to run out on university campuses across the United States, courtesy of a confluence of factors including internal competition for resources, demographics, international competition for students and the unpredictable, long term consequences of SARS-COV-2 for higher education. The United States policy schools have justified their existence on their campuses predominately by their ability to recruit sufficient numbers of paying students to cover their “nut”. I suspect that justification is not going to be enough going forward.

Author: Erik Devereux is a consultant to nonprofits and higher education and teaches at Georgetown University. He has a B.S. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Political Science, 1985) and a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin (Government, 1993). He is the author of Methods of Policy Analysis: Creating, Deploying, and Assessing Theories of Change (Amazon Kindle Direct). Email: [email protected]. Twitter: @eadevereux.

David H Koch

May 2, 2020 at 8:05 pm

I graduated in 1970 with a BA in government specializing in public administration and a minor economics and a MA in government specializing in public administration. I was the only graduate to be able to successfully complete the BA combination at a very large university. The biggest problem with completing the BA and MA combination was the prerequisite courses needed to complete the combination. This was very important since I was completing five years of higher education in four years. I had to skip four math prerequisite requirements needed to complete the economic course requirements. I was only able to do this because of the math and physics courses that I had in high school. I was very glad that I had this combination because it was very easy to get a job in applied economics when I got out of college than in public administration. After 17 years I was able to transition to public administration management and remained there for 23 years to I retired.