Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

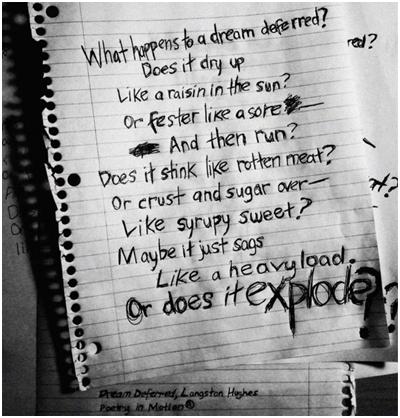

A Dream Deferred? Part II

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Brandi Blessett

June 9, 2015

In last month’s column, A Dream Deferred? I discussed the parallel experiences of Black people in the 1960s and 2015. In particular, I noted the eerily similar aesthetic makeup of communities, then and now: blight, abandonment, disinvestment, crime, police brutality and violence.

In last month’s column, A Dream Deferred? I discussed the parallel experiences of Black people in the 1960s and 2015. In particular, I noted the eerily similar aesthetic makeup of communities, then and now: blight, abandonment, disinvestment, crime, police brutality and violence.

Normative discussions often focus on the inability of low-income minorities to ‘pull themselves up by their bootstraps’ instead of acknowledging the myriad institutional barriers that contribute to disparity and inequality in the first place. If we, as administrators, are interested in living up to the Code of Ethics that guides our profession, I recommend an evaluation of attitudes, actions and behaviors.

Ultimately, the question becomes how do we as public administrators shift toward true and meaningful social progress?

ASK QUESTIONS. The bold and arrogant assumption that administrators know what is best for low-income urban residents is problematic. The same deference given to affluent populations with respect to planning and policy decisions need to be given to low-income populations as well. The best way to bridge the trust and communication gap between traditionally marginalized communities and public administrators/officials is to not only ask questions, but be receptive to what residents have to say.

LISTEN, SILENT. I recently attended a re-entry graduation, where six participants received reduced probation/parole based on their participation and completion of a 52-week intensive supervisory program. One participant spoke about recognizing that “listen” and “silent” were spelled with the same letters, but each word independently was relevant to his overall success. In essence, there are times when he needed to remain silent and listen to what is being said.

Although administrators have the credentials and technical expertise to do their respective jobs, it is important to recognize the expertise of the citizens who live in the communities for which we work and serve. Residents, better than anyone else, know about the existing traffic issues, problems with garbage pick up, which street lights are out and other issues specific to their community. In this case, administrators need to listen and remain silent when residents identify problems or areas of concern within their communities.

FOLLOW THROUGH. From both an academic and practitioner perspective, it is important to be transparent during interactions with residents and communities. Engaging with citizens after meaningful decisions have already been made does nothing to build trust or demonstrate a commitment to the residents. Subsequently, it widens the chasm that already exists between residents and administrators.

EDUCATE THE CITIZENRY. As administrators, it is important that we inform the citizens of plans and programs that are emergent or on-going in their respective communities. I would argue that citizens want to know that their voices have been heard. Therefore, even if decisions were made counter to their personal interest but explained based on sound and reasonable criteria (e.g., funding, personnel, implementation), then residents would have been happy to be meaningfully engaged in the process.

OWN YOUR BIAS. Bias is a fact of life. Everyone has bias toward someone or something and that really is OK. The problem becomes when administrators are unwilling to acknowledge their bias, personal or professional, and as a result do not recognize how that bias, consciously or unconsciously, influences the decision-making process with respect to specific groups and communities. Anyone who says that they do not have bias is a liar, plain and simple. The ability to own and modify your actions around biases helps to create a more responsive administrator.

EVALUATE INSTITUTIONAL PRACTICES. Bureaucratic structures inherently are discriminatory. The hierarchical structure and value premises of economy, effectiveness and efficiency de-emphasize the reality of context, history and politics. As a result, bureaucratic institutions operate under the guise of objective actions, neutral actors and colorblind policies to promote an appearance of fairness.

Additionally, Ward and Rivera in the book Institutional Racism, Organizations and Public Policy recognize that organizational culture, the social constructions of deservingness and bias (personal or professional, intentional or unintentional) are influential in not only maintaining the status quo, but characteristically responsible for perpetuating discrimination. The result undermines equity and discussions become too difficult to measure, costly or time-consuming to pursue. When disparity is clearly aggregated along the lines of race and class, all hands should be on deck to mitigate and reverse such trends. Today, even with all the research that outlines the causes of disparate treatment, society still turns a blind eye to the realities faced by people of color.

The way we engage in low-income communities of color MUST change. Otherwise, rhetoric truly trumps reality. Cultural competence is key to recognizing and appreciating that diverse stakeholders can meaningfully contribute to the policy process. Obtaining cultural competence is both an individual and institutional process.

Individuals must be willing to recognize their bias, modify their respective behaviors, but also understand that to be culturally competent is an on-going learning endeavor. There is not one set of skills that a person attains for a lifetime. Institutions must be willing to fully examine its infrastructure (e.g., policies and practices) and dedicate the necessary resources to support organizational changes that produce equitable outcomes.

Author: Brandi Blessett is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Policy and Administration at Rutgers University-Camden. Her research broadly focuses on issues of social justice. Her areas of study include: cultural competency, social equity, administrative responsibility and disenfranchisement. She can be reached at [email protected].

Follow Us!