Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

To What End? The Impact of Continuing Resolutions on Government Effectiveness

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Nicholas Mastron

February 2, 2018

While the U.S. government remains shut down, many see a continuing resolution as the only foreseeable hope to reopening the public sector. In fact, some commentaries have begun to suggest that government could broadly function better through these funding avenues. While these perspectives and objectives merit some discussion, continuing resolutions, upon closer inspection, ultimately fail these objectives.

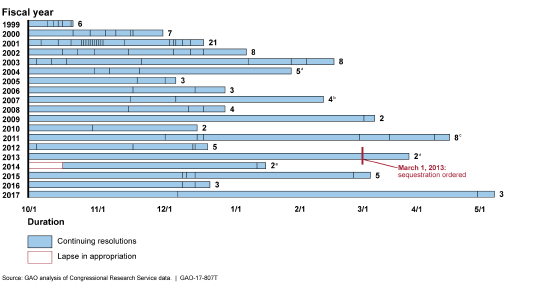

A continuing resolution funds all or specific programs and departments of government until a regular appropriations bill can be enacted. As the recent expiration of the Children’s Health Insurance Program in September 2017 highlights, some programs may lose funding all together until full appropriations can be granted. Yet, as shown in the graphic below, continuing resolutions have become more common and taken on a much more sinister political character—referring to the tendency to occur more in non-election years—over the past two decades.

On the surface, continuing resolutions do what the legislative and executive branches fail to do, which is literally funding governmental activities. While seemingly an inane observation, failure to fund the government could theoretically wreak havoc upon reelection bids. However, the 2013 federal government shutdown did not seem to impact Congressional Republicans in 2015, who actually gained seats despite being in the majority during the initiated shutdown. So, political, not program or mission-driven, timing of continuing resolutions requires consideration too.

Beyond this positive motivation exists another, if more ideological, outcome: government as a subscription-based service. In the era of Netflix, Spotify and even grocery delivery services that are month-to-month, some people have begun asking whether government would be better by only paying for what we as a country (or at least partisan coalitions) want.

This argument harkens back to the public choice discourses of the 1960’s and 1970’s, but with a disfiguring philosophical twist. Now that appropriations bills host this philosophical forum, Congress and the Executive Branch pay not for what services and goods citizens want or need but what they believe people use most when it comes to continuing resolutions. The drastically shorter time periods for military and defense-related departments and programs compared to public housing and commercial oversight evidence this perspective.

Contrasting the political and ideological aspects, nearly all public budgeting analysts and scholars challenge the managerial and technocratic effectiveness of continuing resolutions. Some of the more common issues cited include: workforce development stunting; operational and outreach limitations; contracting changes; programs’ decreased efficiency and increased costs; and potentially agency disenfranchisement.

Those providing public goods and services experience immediate impacts from continuing resolutions. Some civil servants may be furloughed; others may be denied their initial start date; and still more may have to undergo radical shift changes to accommodate the restrictions imposed from the short-term funding legislation. Public managers must also delicately communicate the process to subordinates to retain their morale, some of which invariably escapes. Another human capital loss is decreased training opportunities and travel allocations, which can in turn cripple the operational and outreach integrity for many government programs.

Another elemental flaw with running a government by continuing resolutions is that it completely ignores the private-sector partners in federal contracting. Depending on the funding nature of a given project, many federal contractors additionally find themselves particularly vulnerable to continuing resolutions and public shutdowns. Even if funding has previously been granted, certain client agencies may be deemed nonessential or workspaces closed, prohibiting performance and work requirements for billing. Additionally, due to few companies being able to absorb these fiscal breaks, decreased competition for federal contracts ensues.

Regarding decreased program efficiencies and increased costs, both initial and future costs to both concerns arise. Just this past week, the U.S. Navy, which historically faces fewer continuing resolutions than most other agencies, announced that more than $4 billion has been lost due to continuing resolutions since 2011. Another flawed assumption is the continuing resolutions correctly allocate funds to the correct accounts for the proper agency missions, which is not always the case.

A final charge against this denigrated laissez-faire philosophy of pay-for-use government through continuing resolutions is that it fundamentally pits agencies against one another by ascribing a worth to agencies’ fiscal timelines, personnel needs and even missions. This disparate administrative treatment further hollows out government and encouraging policy territory warring within agencies. Furthermore, it disenfranchises many of America’s most vulnerable citizens who need these public goods and services, but because fewer people utilize Section 8 housing, Congressional and Executive leaders devalue these needs over those with higher usage, like defense or transportation.

In short, continuing resolutions never fully resolve governmental goods and services. Instead, they act like someone who’s just had a car accident and thinks Pop-a-Dent can fix an entire quarter-panel’s worth of damage. Sure, it may lift the battered frame off the tire to drive again, and similarly, on paper, the departmental ledgers are balanced once again, but the legacy costs, quantifiable social costs, remain.

Politics and ideology have led to continuing resolutions’ rise, and they may be our only option presently. Yet, in the long run, continuing resolutions will invariably lead to the destruction of American fiscal integrity.

Author: Nicholas Mastron is a current doctoral student in Public Policy & Administration at the George Washington University, with a field specialization in Social & GenderPolicy. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him @NicholasMastron.

(5 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(5 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

Follow Us!