Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Ethical Accountability in E-Government

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Caitlin P. Stein

October 30, 2015

In a technologically advanced time when public administrators strive to provide the easiest access to services, we see many services being integrated to an online format. Basic “netiquette” provides standards of care when public administrators are accessing Internet sites, but these rights are sometimes taken for granted in our government offices. E-government and Internet-friendly offices can be an ethical dilemma if rules and ethical codes are not maintained accordingly. E-government ethical accountability can be applied to both consequential theory in the form of universal ethical egoism and utilitarianism and non-consequentialism in the form of rule theories and Kant’s duty ethics.

Ethical considerations for e-government situations call on knowledge in the ethical fields of computers, personal information, business and cyber awareness. E-government ethics has been defined by Arief Ramadhan, Dana Indra Sensuse and Aniati Murni Arymurthy as, “Ethics in the use of e-government system, either to insert or update content into the system or to get content from the system; the use of Information Technology (IT) by public sector organizations.” Therefore, the use of Internet capabilities in the field of public administration opens administrators to the concern of moral decisionmaking skills within the public offices.

Universal ethical egoism and utilitarianism

In Ethics: Theory and Practice, Thiroux and Krasemann state, “Universal ethical egoism asserts that everyone should always act in his or her own self-interest as it applies to the possible consequences.” When considering the consequences, the pros and cons are relatively equal. However, ethical egoism changes based on point of view. When everyone is acting in his or her own self-interest, the usefulness of implementing ethical considerations in public administration offices seems moot. An administration official will not be personally affected by negative occurrences unless their position or profession is threatened. Therefore, the official will not see use in the implementation until it becomes too late. The citizen will feel the same way. For example, if the issues do not affect them, citizens will feel adversely to paying higher taxes for the sake of others’ secured information.

Utilitarianism considers the best practice as the one that brings about the greatest good. However, like ethical egoism, the viewpoint may alter the opinion of what is the greater good. If a public administrator believes privacy and security are important, they will believe implementation of a new program will bring the greatest good. However, if the administrator does not believe these are important aspects, then they may feel that it brings more loss than good.

Non-consequentialist theory

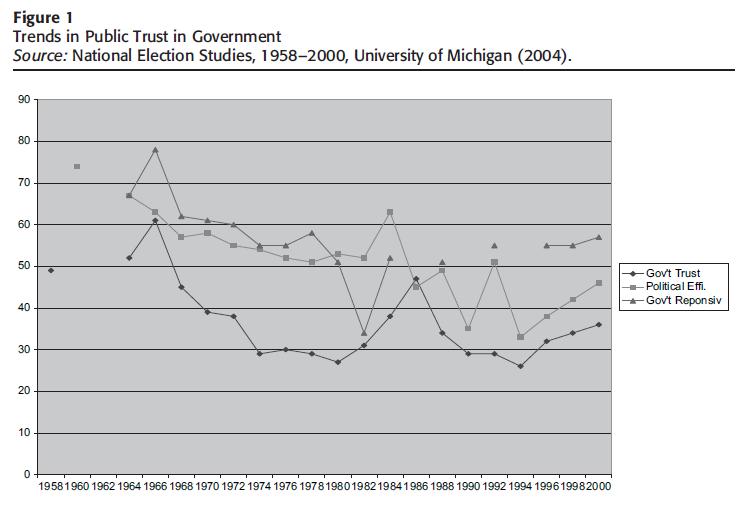

Non-consequentialist theory assumes that consequences do not pertain to the judgment of morality. In the ethical considerations of e-government, act non-consequentialism best fits into the argument. Act non-consequentialism follows the assumption that there are no universal moral rules for every situation; rather, they vary based on the situation. When considering ethical e-government scenarios, the need for implementation of ethical codes will vary based on different personal factors of each organization. E-government supplies ease and affordability for citizens to complete needed transactions. Government trust is directly related to their efficiency as asserted by Eric Welch (see figure). However, many administrative offices do not directly supply services to the public.

An office with four personnel with limited use of Internet services would not need implementation of such strict codes and rules as much as one with 300 personnel and constant Internet access. In “Opportunities and threats: A security assessment of state e-government websites,” Jensen Zhao and Sherry Zhao highlight that an effective e-government office will need to continually update their security measures. For an office with limited use and personnel, this may be less cost efficient.

We cannot generalize the need for ethical e-government of all administrative offices under act non-consequentialism. However, in “Determinants of E-Government Development: Some Methodological Issues,” Isabel-María García-Sánchez, Beatriz Cuadrado-Ballesteros and José-Valeriano Frías-Aceituno state that better governance relating to ethics is required for electronic implementations of any kind. Therefore, we can only assume that not following ethical considerations in electronic usage in public administration offices is immoral.

The application of consequentialist and non-consequentialist theories vary based on subject matter. When discussed in the realm of e-government, non-consequentialism appears to be the most substantial. Where no administrative offices are equal, act non-consequentialism takes into consideration these differences and inequalities.

Author: Caitlin P. Stein can be reached at [email protected].

Follow Us!