Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Ethical Blindness in Public Life

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Terry Newell

July 12, 2016

There are volumes of ethics laws for public servants and training alerts them to these requirements. So, why did schedulers at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) falsify patient appointment wait times? How did the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) end up singling out conservative groups for special scrutiny in their applications for tax-exempt status? These actions were not illegal, but they were unethical. Clearly, ethics laws cannot guarantee ethical behavior. Something is wrong that legislation could not and cannot fix.

The ethics apparatus in government does much good, but its subtle message can be: “If it’s not illegal, it must be OK.” The focus on what not to do can excuse public servants from thinking carefully about what they should do.

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, dogged by her decision to use a private email server, tried to put that controversy to rest by saying it was for convenience. In short, she saw a management problem and chose an efficient response. She did not see (others might argue did not care about) a lurking ethics issue: a conflict in moral values. How should she balance efficiency with transparency and privacy with full disclosure? In failing to confront this question, she invited questions about her integrity.

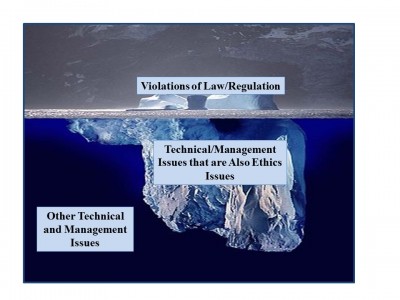

The Ethical Iceberg

She is not alone, as the VA and IRS also now know. Such problems can emerge from a blind spot. Ethics issues are embedded in some decisions that appear to be solely management or technical questions. Thinking of all the potential ethics issues we might face as an iceberg floating in the ocean of government decision making, those that involve questions of law and regulation are the tip of that iceberg, the part visible above the water. We can see them coming. Yet there are ethics issues below the water line, hidden from view in what appear to be just management or technical problems, waiting to tear into the hull of our integrity and effectiveness. We are not willfully unethical. We just don’t see what we need to see.

Motivated Blindness

Motivated Blindness

So, the VA, IRS, and Secretary Clinton might have had ethical myopia. Work by business professor Max Bazerman suggests that there can also be another kind of ethical blindness. Sometimes it is in our self-interest not to see an ethical dilemma. VA supervisors, intent on meeting wait-time performance metrics, had a powerful incentive to ignore the ethical consequences of the pressure they put on schedulers. The IRS, faced with an overload of applications, had an incentive to ignore the ethical implications of grouping “like” applications. Bazerman calls this motivated blindness because while we want to be ethical, when it does not seem in our self-interest, we can be unethical.

Is There a Way to “See” More Clearly?

Avoiding ethical blindness is hard to do alone. We don’t see what we can’t (or prefer not to) see. There are, however, ways to sharpen our ethical eyesight:

- Improve the ability to spot value conflicts to ensure you know when you have an ethical dilemma. As illustrated partially below, at least three values sets may be at work in any government decision. Conflicts can occur within or across values sets. At the IRS, for example, efficiency conflicted with equality and fairness.

| Constitutional Values | Organizational Values | Personal Values |

| Representative government | Efficiency | Achievement |

| Due process | Effectiveness | Honesty |

| Separation of powers | Chain of command | Fairness |

| Equality | Timeliness | Compassion |

| Responsiveness | Collaboration | Responsibility |

| Subordination of military | Creativity | Freedom |

| to civilian authority | Stewardship of resources | Loyalty |

- Bring in other viewpoints, especially from people without a vested interest in the issue or in pleasing you. They may spot value conflicts you can’t. They may see where motivated blindness lurks.

- Think about the public servant you want to be. Ask yourself: is what I am planning to do consistent with my commitment to public service and my cherished values?

- Watch out for rationalizations, such as “it’s legal,” “everyone does it” and “I had no other choice.”

- As Bazerman suggests, be wary of language euphemisms. “Enhanced interrogation techniques” replaced “torture” in the language about prisoner interrogation, enabling many to blind themselves to the ethical questions they should have confronted.

- Don’t act in the heat of the moment. Lots of unethical decisions get made under the pressure of time, circumstance and emotion. When these are at work, consider any decision as tentative. Revisit it the next day, when you have had a chance to calm down.

Hardly any public servant wants to be unethical. Many that end up crossing ethical boundaries wonder how it happened. Avoiding ethical blindness won’t solve every such problem, but good sight is better than hindsight.

Author: Terry Newell is president of his training firm, Leadership for a Responsibility Society and is the former dean of faculty of the Federal Executive Institute. His latest book is titled, To Serve with Honor: Doing the Right Thing in Government. Email: [email protected].

(2 votes, average: 3.50 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 3.50 out of 5)

Terry Newell

July 14, 2016 at 10:41 am

Thanks very much for your thoughtful email and comment on my article. I certainly agree that every public servant must ensure he or she knows what the law requires and follows law and regulation. I agree with you that one’s internal moral compass is not an acceptable substitute for the law (except perhaps in extreme cases, where the law is clearly unjust, as in Nazi Germany and in many situations in the segregated South, for example). To glibly substitute one’s own version of morality for the law is to practice civil disobedience, which would make it impossible for government to function through government employees.

My column was trying to address situations where there is no violation of law as a concern – where all one’s choices as a public servant would comply with the law. My view is that there are still ethical dilemmas that arise – even when actions are perfectly legal. To take a simple case: what does a supervisor do when asked by an employee to give a reference to a prospective employer, when the supervisor knows the employee is not that good but would dearly like to get rid of him or her? If the supervisor is honest, the employee does not get the job. If the supervisor lies, the employee does get the job. This is an ethical dilemma that no law addresses.

To take a more complex case: what does an employee do when asked by his boss to withhold information because it will make the office look bad? Or, to take yet another case you mention: is it really OK to lie even if not under oath or FBI interrogation? And when is it OK to lie? In my work with government executives, I find them deeply troubled by such questions – ethical dilemmas that the law does not satisfactorily address.

In the case of the IRS, I agree that there is no evidence a law was broken. Yet a sensitive public servant should have asked himself: if we group organizations this way, might we be perceived by the public as “going after” certain groups (even if we are not)? Because, if we are perceived that way, this hurts our credibility and damages our organization. That’s the ethical sensitivity I think is missing in such situations.

In the case of enhanced interrogation, this was confronted as an ethical issue by such people as Navy General Counsel Alberto Mora, who was deeply troubled on ethical grounds that – legal opinions to the contrary – these techniques were un-American and violated his sense of the Constitution and our commitments under the Geneva Conventions. Mora felt that to just go along because the lawyers said it was OK was a denial of his obligation to his Constitutional Oath of Office. He was willing to pay the price for that dissent, which to me marked him as an honorable public servant.

John Pearson

July 13, 2016 at 12:45 pm

Sorry to have to disagree with this somewhat. The primary concern for most federal employees is staying within the law. In the federal government, there are a great many ethical rules codified in law (as well as many other rules such as FOIA rules and federal records rules). We had to take annual ethics training and it was always about ethical rules in law rather than ethical concepts outside of law. For example, it’s unethical (and illegal) to use your job for personal gain. That was in the training. There was no discussion of lying because lying is not illegal (except under oath or in an FBI interview).

The problem with ethical rules outside of law is there is no agreement on what they might be. People have very different internal moral compasses. What is deeply offensive to one person might seem ok to someone else. We can see that clearly demonstrated in the current political campaign.

Hillary was clearly investigated for possible violations of law. In fact, the FBI would never investigate alleged unethical behavior unless it was possibly a violation of law. She should have been attuned to the risk of being charged with security violations, records violations, FOIA violations. Her opponents have brought up specific legal issues not vague ethical charges.

I’m not convinced the IRS did anything wrong by grouping organizations that appeared on the surface to be engaged in mostly political behavior (and not entitled to tax exemptions). They have a duty to act efficiently. If it can be proved anyone acted in a partisan manner, they should be prosecuted. I don’t see this episode as an ethical lapse.

Same with the employees who carried out enhanced interrogations. Their superiors told them it was not torture in the legal sense. Administration lawyers did confront the issue. It’s not fair to retroactively charge employees who carried out enhanced interrogations with ethical lapses.

In summary, It’s fine for employees to consult their internal moral compass. But they have to realize this really is a nation of very complex laws and they need to be very sensitive to what their legal liabilities could be when they make decisions.