Ethical Pedagogy: Contending with the Effects of Ego Depletion

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Richard Jacobs

July 13, 2018

It’s not unusual for employees working in public organizations to feel pressed for time. With morning hours morphing into afternoon hours and Mondays into Fridays in an unrelenting, repetitive cycle, the pressure generated by juggling multiple and sometimes conflicting personal and professional demands—while simultaneously having to get work completed on schedule—oftentimes tempts employees to submit incomplete reports or fudge facts. Then, upon reviewing those reports, a public administrator discovers ethical lapses.

Understanding the pressures one’s employees are experiencing and that they’re tired, distracted and perhaps feeling guilty, what’s one to do?

“Ego depletion” and unethical conduct

Maryam Kouchaki’s early research revealed that unethical workplace conduct tends to increase when employees are in a state of “ego depletion.” Worn down from fatigue, physical discomfort or the exhaustion that’s associated with making personal and professional difficult choices, employees tend to make unethical decisions and engage in unethical workplace conduct, particularly during the afternoon hours.

Why? The cognitive resources required to resist the those temptations gradually drain as the workday progresses. “Our self-regulatory resources are limited,” Kouchaki noted. “When you use those resources, they are depleted, and you have to replenish them to be able to use them again.”

Ego depletion and an administrator’s perception and judgment

Does knowing that one’s employees are pressured influence an administrator’s perception and judgment of their performance?

Kouchaki’s more recent follow-up research responds in the affirmative: Administrators judge employees’ ethical lapses less severely when they perceive their employees are pressured. Administrators tend to be particularly understanding when those employees are pressured for reasons beyond their control, for example, they had to stay up late into the previous night to deal with a family emergency or they’re overwhelmed by their workload. In particular, devotion to others—for example, reporting “I stayed up to care for a sick child”—tends to earn greater leniency than does honesty — for example, reporting “I stayed up to watch the NBA finals.”

In sum, administrators judge intentional unethical workplace conduct as more blameworthy. They also tend to be more lenient with and rarely punish what they perceive as an employee’s unintentional unethical workplace conduct.

Implications for promoting ethical culture in the workplace

When judging unethical workplace conduct, it’s necessary for public administrators to consider an employee’s situation and circumstances. But, Kouchaki warns, doing so risks setting a dangerous precedent: When an administrator rarely punishes ethical lapses due to ego depletion, the next time an employee acts unethically, there’s little incentive for that employee to be honest about the cause(s).

The best way administrators can limit unethical conduct, Kouchaki observes, is to ensure that employees do not become ego depleted. They do so by making “structural changes such that people could disengage from work when they got home rather than being on call all the time and being anxious about it.”

Ethical pedagogy and promoting ethical culture

As understandable as being lenient may be due to particular situations and circumstances, doing so fails to promote ethical culture in the workplace. To rectify this failure of ethical leadership, Kouchaki maintains, administrators must ensure there are consequences for unethical workplace conduct and uphold those consequences. This is how administrators can assist employees to learn from their ethical lapses and failures, even if they are small or relatively common, and promote ethical culture.

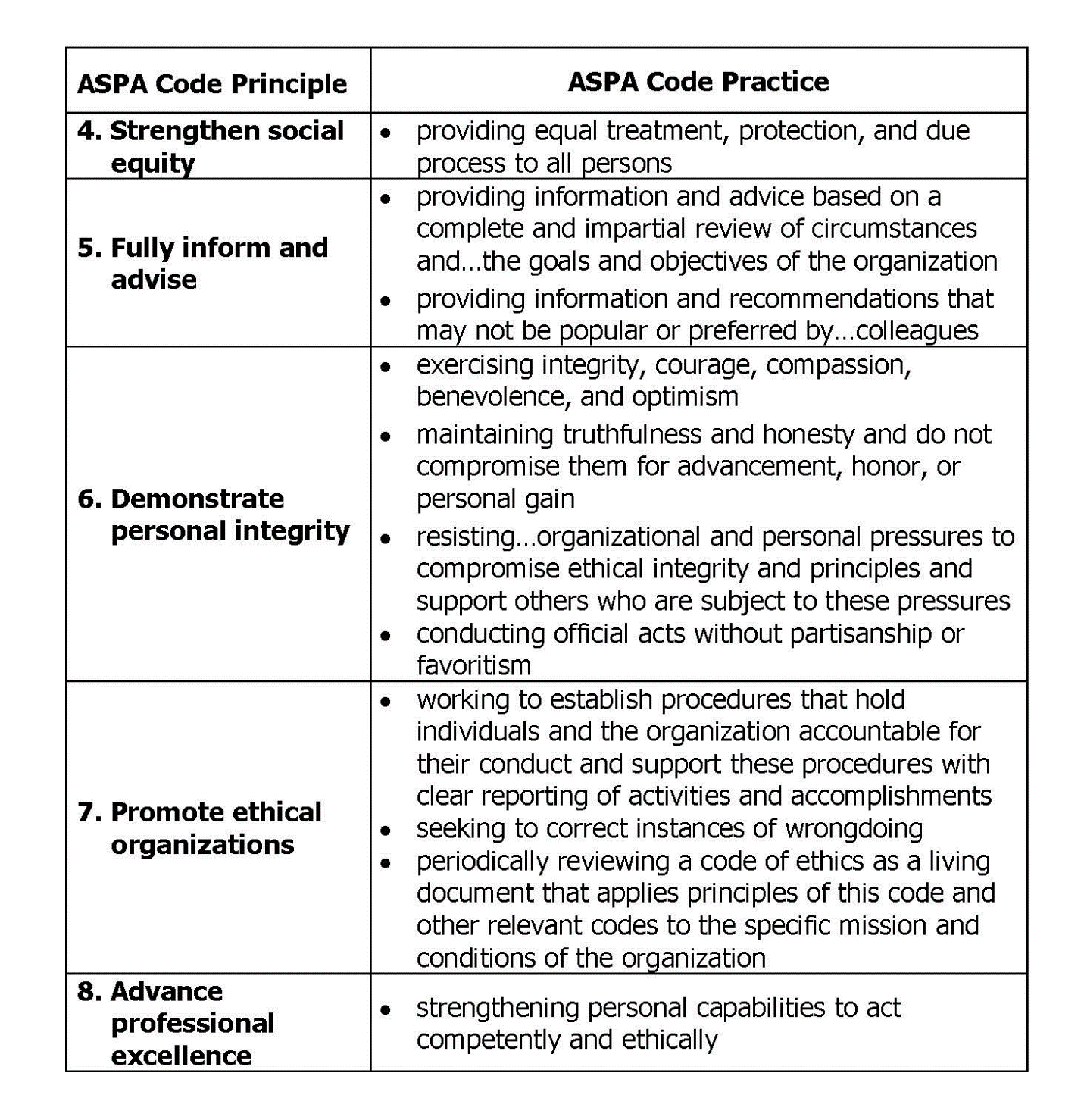

From a human resources perspective, Kouchaki’s prescription makes eminent sense. But, ASPA’s Code of Ethics and Practices (2013) offers a principled alternative. When confronting ethical lapses on the part of employees, public administrators should consider the contents of the following chart:

As personal and professional demands increase and employees endeavor to balance the multiple and conflicting pressures, the result may be that ego depletion causes small ethical lapses increase in frequency. To deal with this challenge, the Code’s contents advocate that public administrators address the effects of ego depletion not by restructuring the workplace but, instead, by reframing those ethical “failures” as “opportunities” for employees to learn from them.

More importantly, the Code’s five principles and twelve practices offer public administrators a roadmap for addressing ethical lapses due to ego depletion by reaffirming the organization’s mission, values and code of conduct. Implementing this roadmap, public administrators will challenge employees to identify and assess the pressures they experience as well as their need to inculcate into their character and express in their workplace conduct the virtues embedded in the Code’s principles and practices.

This leadership conduct—“ethical pedagogy”—evidences itself in the conduct of public administrators who appreciate and understand this crucial role. With clear perception and keen judgment, these women and men promote the development of ethical culture in the public service organizations entrusted to their stewardship.

Author: Richard M. Jacobs is a Professor of Public Administration at Villanova University, Acquisitions Editor of Public Integrity, and Chair of the ASPA Section on Ethics and Integrity in Governance. His research interests include organization theory, leadership ethics, ethical competence, and teaching and learning in public administration. Jacobs may be contacted at: [email protected]

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

Loading...

Loading...

Ethical Pedagogy: Contending with the Effects of Ego Depletion

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Richard Jacobs

July 13, 2018

It’s not unusual for employees working in public organizations to feel pressed for time. With morning hours morphing into afternoon hours and Mondays into Fridays in an unrelenting, repetitive cycle, the pressure generated by juggling multiple and sometimes conflicting personal and professional demands—while simultaneously having to get work completed on schedule—oftentimes tempts employees to submit incomplete reports or fudge facts. Then, upon reviewing those reports, a public administrator discovers ethical lapses.

Understanding the pressures one’s employees are experiencing and that they’re tired, distracted and perhaps feeling guilty, what’s one to do?

“Ego depletion” and unethical conduct

Maryam Kouchaki’s early research revealed that unethical workplace conduct tends to increase when employees are in a state of “ego depletion.” Worn down from fatigue, physical discomfort or the exhaustion that’s associated with making personal and professional difficult choices, employees tend to make unethical decisions and engage in unethical workplace conduct, particularly during the afternoon hours.

Why? The cognitive resources required to resist the those temptations gradually drain as the workday progresses. “Our self-regulatory resources are limited,” Kouchaki noted. “When you use those resources, they are depleted, and you have to replenish them to be able to use them again.”

Ego depletion and an administrator’s perception and judgment

Does knowing that one’s employees are pressured influence an administrator’s perception and judgment of their performance?

Kouchaki’s more recent follow-up research responds in the affirmative: Administrators judge employees’ ethical lapses less severely when they perceive their employees are pressured. Administrators tend to be particularly understanding when those employees are pressured for reasons beyond their control, for example, they had to stay up late into the previous night to deal with a family emergency or they’re overwhelmed by their workload. In particular, devotion to others—for example, reporting “I stayed up to care for a sick child”—tends to earn greater leniency than does honesty — for example, reporting “I stayed up to watch the NBA finals.”

In sum, administrators judge intentional unethical workplace conduct as more blameworthy. They also tend to be more lenient with and rarely punish what they perceive as an employee’s unintentional unethical workplace conduct.

Implications for promoting ethical culture in the workplace

When judging unethical workplace conduct, it’s necessary for public administrators to consider an employee’s situation and circumstances. But, Kouchaki warns, doing so risks setting a dangerous precedent: When an administrator rarely punishes ethical lapses due to ego depletion, the next time an employee acts unethically, there’s little incentive for that employee to be honest about the cause(s).

The best way administrators can limit unethical conduct, Kouchaki observes, is to ensure that employees do not become ego depleted. They do so by making “structural changes such that people could disengage from work when they got home rather than being on call all the time and being anxious about it.”

Ethical pedagogy and promoting ethical culture

As understandable as being lenient may be due to particular situations and circumstances, doing so fails to promote ethical culture in the workplace. To rectify this failure of ethical leadership, Kouchaki maintains, administrators must ensure there are consequences for unethical workplace conduct and uphold those consequences. This is how administrators can assist employees to learn from their ethical lapses and failures, even if they are small or relatively common, and promote ethical culture.

From a human resources perspective, Kouchaki’s prescription makes eminent sense. But, ASPA’s Code of Ethics and Practices (2013) offers a principled alternative. When confronting ethical lapses on the part of employees, public administrators should consider the contents of the following chart:

As personal and professional demands increase and employees endeavor to balance the multiple and conflicting pressures, the result may be that ego depletion causes small ethical lapses increase in frequency. To deal with this challenge, the Code’s contents advocate that public administrators address the effects of ego depletion not by restructuring the workplace but, instead, by reframing those ethical “failures” as “opportunities” for employees to learn from them.

More importantly, the Code’s five principles and twelve practices offer public administrators a roadmap for addressing ethical lapses due to ego depletion by reaffirming the organization’s mission, values and code of conduct. Implementing this roadmap, public administrators will challenge employees to identify and assess the pressures they experience as well as their need to inculcate into their character and express in their workplace conduct the virtues embedded in the Code’s principles and practices.

This leadership conduct—“ethical pedagogy”—evidences itself in the conduct of public administrators who appreciate and understand this crucial role. With clear perception and keen judgment, these women and men promote the development of ethical culture in the public service organizations entrusted to their stewardship.

Author: Richard M. Jacobs is a Professor of Public Administration at Villanova University, Acquisitions Editor of Public Integrity, and Chair of the ASPA Section on Ethics and Integrity in Governance. His research interests include organization theory, leadership ethics, ethical competence, and teaching and learning in public administration. Jacobs may be contacted at: [email protected]

Follow Us!