Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Ethics of Equity

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Stephen M. King

March 17, 2023

In his book Broken Signposts (2020), N.T. Wright argues that many signposts, or markers of life, are damaged, including justice or what some call equity. It is not hard to figure out, for example, that justice is a noble truth and principle—one to strive toward. But according to Wright, even though we intuitively know justice is critical for any society, “…we find it difficult…to achieve it.”

Today, we know that our administrative, political and policy systems are not entirely just, fair or equitable; that individuals and groups, regardless of status, are not always treated the same. But it seems no matter how hard we try, including the yeoman work of public administration academics and practitioners, the signpost remains broken, and the outcome we seek slips our grasp.

In this first of four pieces titled “Ethics of Equity” I argue that our focus should not be solely or disproportionately on a pre-determined administrative, political or policy end or outcome, per se, whether through teaching and research, or administrative and managerial practices. Instead, consider that the goal of our work should be to examine our intentions and motivations for acting, and fix our attention on the ethics of process, rather than running a spirited race to ends or outcomes that are not clear or perhaps not even achievable.

As an academic concept, social equity first surfaced shortly after WWII, with the work of Frances Harriet Williams, former race relations advisor to the Office of Price Administration, who raised awareness to minority presence and participation in federal government programs. But it was not until the turmoil of the 1960s, and ultimately Minnowbrook I in 1968, that social equity gained momentum among young scholars, such as H. George Frederickson. Frederickson, for example, was adamant that those who studied public administration could no longer research and write rhetorically about the need for systemic and institutional change. Instead, true change for equity required not only administrative involvement, but policy action.

Over the last four decades, and even up until his death in 2020, he and others led the charge for capturing what he called the “moral high ground” of social equity, particularly on issues such as poverty, income inequality and others. Still, even with victories, the concept never quite gained the traction Frederickson and others had hope for. Until recently, it always seemed to lack the “Holy Grail” of efficiency, economy and effectiveness.

However, the proverbial tide has turned. The focus on equity in public administration is experiencing a revival, with scholars like Susan Gooden, Brandi Blessett, Kristen Norman-Major, Sean McCandless, Sanjay Pandey and others, pushing the equity scholarship envelope like never before, promoting race and gender-aware issues, for example, that had languished in previous research. There is intense attention directed to equity issues on all levels of government, and in diverse administrative and policy areas. In addition, intersectional and collaborative efforts, both in research and practice, are making significant headway.

Although empathetic to the purpose and vision of the early equity public administration pioneers—a purpose that demanded action—there is the concern that as a public value, equity is still trying to find its ethical footing in the nexus between the administrative and the democratic. Action toward an outcome is a focal point, and always will be, but the ethical means and motivations for reaching the intended target—whatever that might be in any given context—are equally important.

In her remarks after receiving the 2019 ASPA Gloria Hobson Nordin Social Equity Award, Brandi Blessett made several key points directed toward what I call the “ethics of equity.” Growing up in Detroit she described her early years as soul-searching. She wondered why, for example, black communities looked different from other communities she came across on her family vacations and school breaks. Why are there differences? Should there be differences? As a child, she didn’t have the answers, but when she started her Ph.D., she knew she wanted to pursue research that would yield answers to her childhood questions.

Her reality of witnessing differences in black and white communities, neighborhoods, businesses and schools was not only an existential one, but it was also an ethical one. One that demanded an explanation and understanding of the differences, why they existed and what could be done to correct them. Equity was not relegated to an outcome; it encompassed an ethical concern for achieving the greater good for all, not just a few.

Later, she understood that public administration is too often taught, researched and practiced in a historical vacuum. Racial, ethnic, gender and other differences in humanity do not suddenly appear. Instead, they are rooted in historical understanding of administrative, cultural, economic, political and social constructs—constructs that are at their foundation ethical in nature.

She understood that differences exist, but differences that exist because of flawed institutions and organizations are ethically and morally unjustified, regardless of whether they are public, private or nonprofit. And when those differences are magnified and left unchecked, she claimed that “our institutions’ legitimacy is compromised, our constituents’ trust decreases and our pursuit of justice is denied.” Clearly, it seems, the ethical equipoise between the administrative and democratic is not only one of outcome, but is an ethical and moral process and intention, one that if severely and compromisingly displaced, tips the scales from the just to the unjust.

Last, she recognized that public administration scholars, educators and practitioners are responsible for their thoughts, words and deeds. It is the scholar’s responsibility to research and uncover the truths of the inequities and inequalities. As educators, she stated “we have to discern the types and quality of the conversations we have in the classroom.” And as practitioners, we “must recognize that our implicit bias impacts our decision-making process.” We all have the responsibility to confront these concerns, knowing that they have ethical implications and consequences.

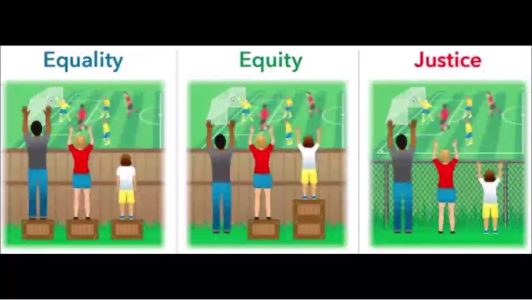

In conclusion, Brandi Blessett eloquently and directly pointed out the pursuit of equity is not, nor should be, relegated to achieving only perceived contextual outcomes. Outcomes are certainly expected, whether they are judicial fairness, safety and security with law enforcement, equal housing initiatives and a plethora of others, but policy outcomes alone cannot be the sole driver for the public administration scholar, teacher and practitioner. If so, then we lose sight of the equally important ethical and moral implications that come with seeking, conversing and overseeing truly fair, just and equal systems that provide opportunities for all. Achieving equity, fairness and justice is a challenging journey, but is one that may help us avoid another broken signpost.

Author: Stephen M. King is professor of government at Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA. He teaches undergraduate courses in American politics, state and local government, and public policy, and graduate courses in public policy analysis. He frequently publishes on the topics of ethics and public administration and leadership, and spirituality in the public workplace. He currently serves on the executive council of Hampton Roads Chapter of ASPA. His most recent book, Ethical Public Leadership: Foundation, Organization, and Discovery, published by Routledge, is due out in summer 2023. Contact him at [email protected].

Mike Abels

March 18, 2023 at 11:36 am

Excellent discussion. You conclude by advocating for the pursuit of equity, fairness, and justice, and in your column praise the field of PA for historical orientation to the ethics of equity as demonstrated by the “New Public Administration” as well as a current revival of a focus on equity in research and practice.

If true that a focus on equity is making significant headway doesn’t that face tremendous political challenges posed by the “anti-woke” MAGA movement? What damages to the practice of PA will be caused by a conflict between the field of PA and a political party that may be the future governing party of the country?a

Michael Abels

March 18, 2023 at 11:21 am

Excellent discussion. You conclude by advocating for the pursuit of equity, fairness, and justice. In your column you praise the field of PA for historical orientation to the ethics of equity as demonstrated by the “New Public Administration” as well as a current revival of a focus on equity in research and practice.

If true that a focus on equity is making significant headway doesn’t that face tremendous political challenges posed by the “anti-woke” MAGA party? What damages to the practice of PA will result from a conflict between the field of PA and a political party that may be the future governing party of the country?