Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Facing Up to Government Sprawl

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Kevin R. Kosar

November 17, 2015

Reducing the size of the federal workforce has become a hot political issue this year.

When the House and Senate drew up their budget plans this spring, both chambers included a provision to shrink the civil service. Rep. Ken Calvert, R-Calif., unveiled a bill in August to reduce the number of civilian defense employees. Shortly after the 114th Congress began, Rep. Cynthia Lummis, R-Wyo., introduced the Federal Workforce Reduction through Attrition Act. It would gradually roll back and then freeze the number of federal employees at 90 percent of the workforce rolls as of Sept. 30, 2013. To reach this target promptly, the legislation would permit agencies to hire a new employee only after three had retired. The idea has attracted a great deal of attention and advocates.

Republican presidential candidates have also taken up the issue. Jeb Bush favors the Lummis “three-out-one-in” hiring curb. Carly Fiorina wants to freeze hiring and shrink the federal workforce by as many as 600,000.

Mostly, the calls for fewer feds have come from the political right, who has tied them to concerns about Washington’s finances. The federal government has run deficits 36 of the past 40 years. “We’ve racked up $18 trillion in debt simply because Washington has no idea when to stop spending,” notes Rep. Lummis. Conservatives are dismayed that few federal employees are fired for low performance or bad behavior. However, it is worth recalling that the bipartisan National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (aka Simpson-Bowles) also proposed civil service cuts.

So, do we need fewer bureaucrats? To answer this question requires first admitting there is no easy way to calculate optimal federal employment. Private-sector firms size their staffs based on market forces. Firms hire as many employees as can productively offer positive returns on the investment in human capital.

The federal government, by contrast, hires as many individuals as Congress permits. Each year, appropriations laws allot funds to pay federal employees. How many individuals our government hires is a function of whatever criteria loom in the minds of legislators. Last year’s staffing levels usually are a key consideration.

Ideally, the number of federal employees should be based on the amount of federal work that needs to be done. That clearly is not happening. Year after year, Congress and the president create new agencies, policies and programs, layering them atop existing ones. Today, the federal government has about 180 agencies although there is no definitive count. As the more than 170,000-page Code of Federal Regulations illustrates, the government’s responsibilities are innumerable and touch upon just about everything under the sun.

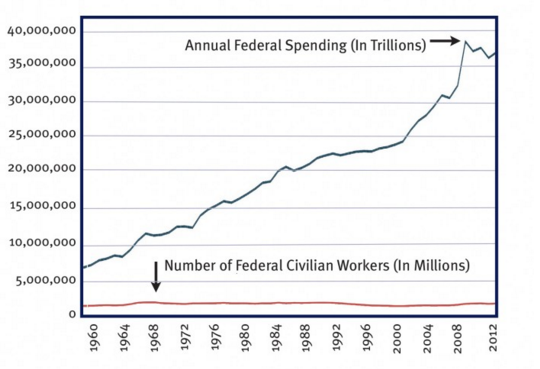

While the reach of government has expanded massively, the federal workforce has not. Currently, about 2 million individuals are employed in the civilian workforce. This does not include the 500,000 persons who work for the self-funding U.S. Postal Service and the undisclosed staff levels for the secretive national security apparatus (e.g., the Central Intelligence Agency). In the past decade, federal employment has increased by a couple of hundred thousand. Over the past half-century, however, the number of feds has been flat and, as the National Academy of Public Administration’s John DiIulio has pointed out, federal spending has quintupled.

This is a ratio for badly administered government, which is what we all-too-often get. As a practical matter, it also has meant outsourcing a huge amount of government work with little oversight. To cite just two examples: the U.S. Defense Department relies on 710,000 contractors, while the federal Head Start program is administered by 200,000 state, local and private-sector employees.

If we are going to reduce the federal workforce, we also need to reduce the size of the government. Cutting federal workers, while assigning them more duties, makes little sense.

Proposals to reduce the federal workforce should incorporate plans to reduce government sprawl and better focus government work. This can be done many ways. Passing a statute to eliminate the requirement that agencies produce reports that nobody reads will free manpower for more useful tasks. So too would allowing agencies to unload buildings they do not need, rather than continue to maintain them.

Congress also could establish an annual exercise, wherein it abolishes antiquated and unproven programs, such as those identified in the president’s annual budget. (This past year, the president proposed more than 130 cuts that would save $17 billion annually. Nearly every federal agency had something on the chopping block.) Alternatively, Congress could draw upon the reports by the inspector generals and the Government Accountability Office identifying ineffective programs.

So do we need fewer bureaucrats? Maybe. We will not know until we decide exactly what it is we want them to do.

Author: Kevin R. Kosar is the director of the governance project at the R Street Institute, a think-tank in Washington, D.C. He was a federal employee for more than a decade. He can be reached at [email protected] and followed at https://twitter.com/kevinrkosar.

Follow Us!