Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

FY 2018: A New Low in Congressional Appropriations?

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Jason Juffras

August 8, 2017

In The Power of the Purse, the classic study of the congressional appropriations process from 1947 to 1965, Richard Fenno declared, “The power of the purse is the historic bulwark of legislative authority.” Today, that bulwark seems to have been abandoned, having crumbled under continued assault by the forces of partisanship. Experts have long chronicled the decline of the appropriations process, but the FY 2018 appropriations cycle presently underway could signal its total collapse.

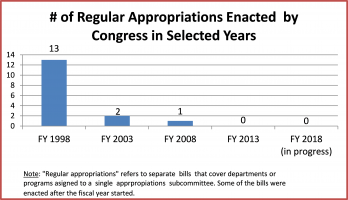

The official process in which legislators enact separate appropriations bills after review and compromise at the subcommittee and committee levels, on the House and Senate floors, and between Congress and the President, now exists mostly in theory. Congress has not enacted all of the regular appropriations bills (presently there are 12 bills, formerly 13) before the fiscal year starts on October 1since fiscal year (FY) 1997. Alice Rivlin, the first director of the Congressional Budget Office, and former Senator Pete Domenici, who chaired the Senate Budget Committee, observed, “In the face of increasing partisan polarization and frequent gridlock, Congress and the executive branch have lurched from one budget crisis to another and kept the government running by means of continuing resolutions and massive appropriations bills.”

Even though the discretionary programs subject to annual appropriation account for only 30 percent of federal spending, or $1.2 trillion (mandatory spending and debt service account for the remainder), appropriations are needed to finance departments such as Defense, Education and Transportation, as well as the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Institutes of Health.

A faltering appropriations process impedes effective performance by the executive branch. Federal agencies funded by short term continuing resolutions are hampered in planning, awarding contracts and grants, and hiring, as shown by University of Maryland professor Philip Joyce. When appropriations bills are merged into an omnibus bill comprising thousands of pages and made public just before a vote, public participation is also stifled.

The appropriations process has fared somewhat better during unified government — when one party holds the presidency and majorities in the House and Senate. Under President George W. Bush, Congress enacted 11 regular, stand alone appropriations bills for FY 2006 when Republicans controlled both chambers, but only one regular appropriation for FY 2008 after Democrats reclaimed majorities in both bodies. Under President Obama, Congress enacted six regular appropriations bills for FY 2010 in the first year of unified Democratic control. This modest achievement was short lived: from FY 2011 (the final year of unified Democratic control) through FY 2017, Congress enacted only one regular appropriation (the homeland security bill for FY 2015).

This history would predict an upturn in appropriations output for FY 2018, due to the return of unified government under President Trump and a Republican-controlled Congress. But by the end of July 2017, Congress had not passed a budget resolution setting spending limits for appropriators or brought a single regular appropriations bill to the floor of either chamber. By contrast, under unified Democratic control, legislators had passed a budget resolution and steered 11 appropriations bills for FY 2010 through the House, and three through the Senate, by the end of July 2009.

Given the dismal record thus far, coupled with unease in both parties about domestic spending cuts proposed by the President, a series of continuing resolutions or omnibus appropriations seems likely for FY 2018. Even worse, the need to raise the nation’s debt ceiling sometime this fall could encourage the brinkmanship that has previously resulted in government shutdowns.

What can be done to revive the moribund appropriations process? Rivlin and Domenici support biennial budgeting as way to bring stability to the budget process and give legislators more time to work on program authorizations and oversight. Biennial budgeting already exists in a de facto sense, as the President and Congress have agreed on successive two-year budget deals (the Budget Control Act of 2011, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015) to keep the government operating. On the other hand, a previous change designed to give Congress more time to deliberate on the budget—shifting the start of the fiscal year from July 1 to October 1 in FY 1977—did not yield better results. Changes that directly target legislators’ self-interest, such as canceling congressional recess or cutting legislators’ pay when appropriations are not enacted on time, might have greater impact.

Former CBO Director Rudy Penner has warned, “The process is not the problem. The problem is the problem.” In other words, biennial budgeting and other reforms may have little effect in the face of large deficits, growing entitlements, political polarization, poor leadership (and followership) and the perpetual campaign. As Rivlin and Domenici warn, “Difficult political decisions demand more than new budget tools. They require political will.”

Author: Jason Juffras has 20 years of experience in state and local budgeting, policymaking, and program evaluation. He earned a doctorate in public policy and administration from The George Washington University in 2015, with a concentration in public budgeting and finance. He can be reached at [email protected].

Follow Us!