Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Why Do Good Leaders Do Bad Things?

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Terry Newell

August 9, 2016

On March 8, 2012, David Petraeus was director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Petraeus was a four-star general, credited with leading the “Sunni Awakening” that enabled American forces to wind down their involvement in Iraq. He has been confirmed the previous July by a 94-0 vote in the Senate. The very next day, Petraeus resigned, acknowledging an extramarital affair with Paula Broadwell, a writer working on his biography. Petraeus admitted to a serious lapse in ethical judgment. Three years later, he would plead guilty to mishandling classified information, having allowed Broadwell access to secret papers.

Petraeus was at the top of his game, rumored to be a presidential prospect. What went wrong?

The Bathsheba Syndrome

“If you want to test a man’s character, give him power,” Lincoln said. Management professors Dean Ludwig and Clinton Longenecker suggest that the power that comes with leadership success can be a problem. They call this the Bathsheba Syndrome. King David saw and desired Bathsheba, the wife of one of his officers. When she got pregnant, David tried to entice her husband to return from war to hide his sin. When Bathsheba’s husband insisted on remaining in the field, as honor demanded, David ordered him to the front, where he knew he would be killed.

Ludwig and Longenecker argue that leadership success brings benefits on personal and organizational levels. A leader rising up the hierarchy gains more influence, status, perks, control over decision making and less direct supervision. Yet with these benefits come potential dangers. Stress increases, as does isolation from dissent, imbalance in one’s personal life and the danger of an inflated ego. Unchecked, these can lead to a loss of strategic focus, a tendency to operate on autopilot and to ignore important leadership tasks. Thus, the very benefits that come with success increase the risks of acting unethically. Petraeus may have succumbed to the Bathsheba Syndrome.

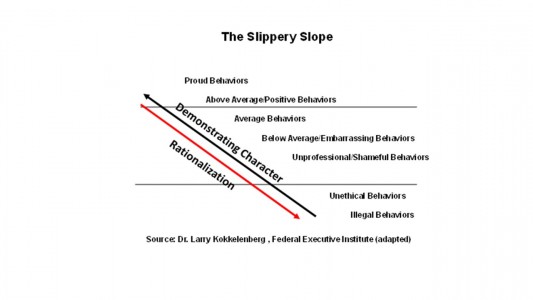

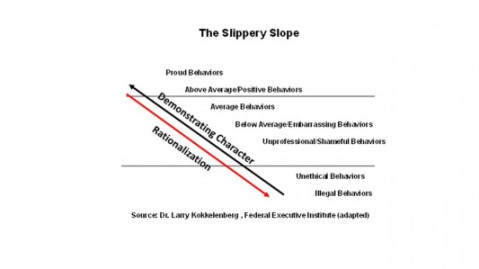

The Slippery Slope to Unethical Leadership

Juvenal, the Roman poet, quipped that “[N]o man ever became extremely wicked all at once.” While some leaders are evil, most don’t start out that way. However, they can slide down the slippery slope of unethical behavior without noticing the compromises they are making. Each step down gets justified through rationalization. At some point, they cross the line perhaps even unaware.

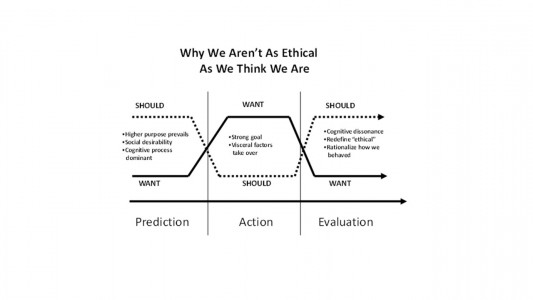

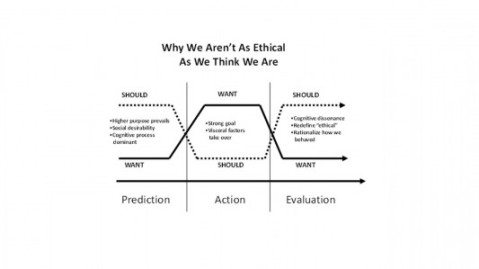

The Should-Want-Should Cycle

Petraeus acknowledged his ethical failure, but some leaders are shocked that people think they have acted unethically. They just can’t see it. Ann E. Tenbrunsel and her colleagues explain how this can happen. They posit three “selves” or phases we can go through when facing an ethical challenge. Before acting, we are in “should” phase, the state where we know what our own morality and social convention require and rationally predict we will act ethically. But in the action stage, our “want” self takes over. Emotional and other pressures overcome our cognitive predictions. We go astray. Then, in the post-action evaluation phase, we grapple with the disconnect between our predicted and actual behavior. The “should” re-asserts itself, so we go through mental gymnastics to restore our sense that we are a good person.

How Can Good Leaders Stay Good?

How Can Good Leaders Stay Good?

Forewarned is forearmed, but that is not enough. A leader who wants to remain ethical must augment knowledge about what can go wrong with action.

- Check your ego. Find people who will tell you when your inflated sense of self is heading for an ethical accident. In ancient Rome, the victorious general would drive his chariot in a triumphal procession. Standing behind him, a slave would whisper in his ear that he was just a mortal man.

- Foster dissent. Ensure direct reports will disagree with you. Encourage and reward dissent. General George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff during World War II, solved this problem early in his tenure. In one of his first meetings with senior staff, after listening to their comments on his plans, he told them: “Gentlemen, I am disappointed in you. You haven’t yet disagreed with a single decision I’ve made.”

- Lead a balanced life. When your job and its power become your life, when the thought of losing them is so frightening that you would do almost anything to prevent that, you set yourself up for acting unethically.

- Calm the decision making cauldron. When you feel strong emotion around a decision, slow yourself down. Make sure your desired self stays in charge. Invite trusted colleagues into the process to check your thinking. Do an “implications test”: if I do this, then what might happen? Will I still be proud tomorrow?

Stephen K. Bailey once said that ““In general, the higher a person goes on the rungs of power and authority, the wobblier the ethical ladder.” But good leaders don’t have to fall off.

Author: Terry Newell is president of his training firm, Leadership for a Responsibility Society and is the former dean of faculty of the Federal Executive Institute. His latest book is titled, To Serve with Honor: Doing the Right Thing in Government. Email: [email protected].

(4 votes, average: 4.75 out of 5)

(4 votes, average: 4.75 out of 5)

Pingback: The Danger of Telling the Truth | PA TIMES Online