Infrastructure – Technologies Delivering Impact and Value 2.0

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Daniel G. Bauer

May 30, 2017

Discourse surrounding U.S. infrastructure and its present state of operating capacity is dominated by substantial costs to upgrade and/or costs attributed to new construction. Either way, the issue of infrastructure seems to be increasingly categorized as a ‘wicked’ policy problem, Pressman and Wildavsky in 1973 indicated complex policy programs’ ultimate successful resolution were impossible due to, among other issues, lack of goal clarity, information and coordination altogether too difficult to meet. Infrastructure surely seems to fit that category of complexity and wickedness.

Brian Head of the University of Queensland defined wicked policy problems in his 2008 article published in Public Policy as “complex, intractable, and open-ended.” Furthermore, he asked the question as to whether we are developing better ways of addressing such wicked problems. The singular focus of this second article continues where the first article left off — on the impact of technology, as a way of addressing old age infrastructure.

How do we define technology impact? What technologies do we utilize? Assessing the impact of technologies upon U.S. infrastructure includes three distinctive areas of inquiry: productivity, costs and extending the end of product/project lifecycle (EEOPL). A fourth area of impact is emerging as a standard and that would be environmental. To answer the second question, two types of technology classifications would compose the framework for assessing impact: information communications technologies and physical technologies. These technologies will be listed later in this article as we turn the focus back towards the infrastructure categories.

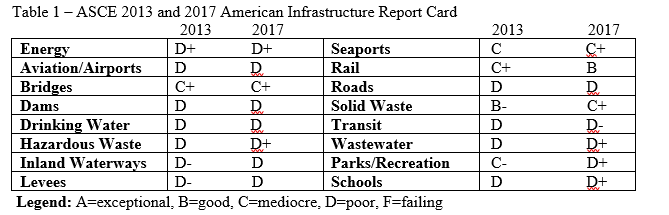

Soon after the first article in this series on Infrastructure and Technology Impact, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) released their updated 2017 American Infrastructure Report Card this past March. As Table 1 indicates below, minimal progress and in most cases, zero progress has been achieved since the last report card in March 2013.

The overall 2017 grade remained the same as 2013: D+. Moreover, the costs to finance the upgrades and/or new construction is estimated to approach $3 trillion by 2020. Conventional wisdom regarding infrastructure posits that the product/project lifecycle and subsequent financing reasonably match up in terms of length of service. However, the infrastructure status is poor and depreciated way beyond its lifecycle. Furthermore, impacts upon environment certainly need to be assessed as infrastructure projects such as roads and dams possess costly implications as evidenced by recent events in California. Meanwhile, productivity increases are required for overall national economic improvement. In other words, is this evidence of a wicked problem? Can technologies provide a collective impact?

In 2001, at the height of the internet bubble, Diewald described in Public Works Management & Policy that technology—and innovation-induced change—“provides opportunities for improvement and that technology developments in materials, electronics, information communications technologies (ICT) can assist in meeting future demand for all infrastructure facilities.” Fast forward to the present state and Frankel and Wachs in their recent 2017 article on infrastructure and governance in Public Works Management & Policy discuss the implications of collective asset management involving more than just money pertaining to infrastructure facilities.

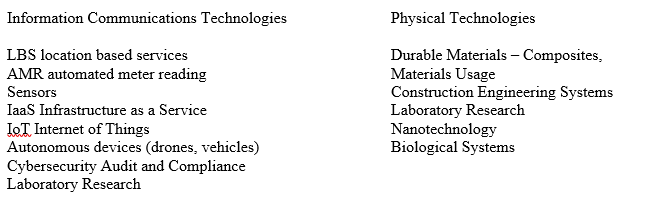

At this point in the discussion, infrastructure, in its present state and age, poses a complex, wicked problem to business, government, and society, collectively. However, technologies have provided solutions at various levels (low, medium, high) of impact upon the four areas (productivity, costs, EEOPL, environment) as well as upon each of the 16 categories listed by the ASCE. These technologies comprise the framework. The technologies represent general areas and are not meant to be all inclusive but are meant to provide a platform for discussion and analysis. The technologies are listed below:

A detailed explanation for each of the 14 technologies listed above, as well as level of impact upon each of the four impact areas, will be juxtaposed to the 16 categories of infrastructure in the forthcoming third article in this series on Infrastructure and Technology.

Finally, the use of such technologies not only possesses impact but may lead to resolving some of society’s most pressing environmental, social and governance issues, such as social equity, intergenerational equity and social responsibility, while unveiling new collective innovations for business and government financing mechanisms such as public-private partnership monetization, and asset pooling, as well as others.

One may argue the wicked problem, that is, the aging and present status as well as costs associated with upgrading and constructing new infrastructure has spawned growth in technologies. Do we have an infrastructure issue in search of a solution? Or, do we have technological solutions in search of a market such as infrastructure?

Author: Daniel G. Bauer is finishing his Doctorate at the School of Public Administration at Florida Atlantic University. Mr. Bauer has an Executive MBA from the College of Business at Florida Atlantic University and a BBA in Finance from University of Toledo. Daniel has 20+ years of professional experience both domestically and abroad. His research areas focus on finding solutions at the confluence of financing, procurement/supply chain, organizational behavior, sustainability, and social responsibility.

(6 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

(6 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

Loading...

Loading...

Infrastructure – Technologies Delivering Impact and Value 2.0

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Daniel G. Bauer

May 30, 2017

Discourse surrounding U.S. infrastructure and its present state of operating capacity is dominated by substantial costs to upgrade and/or costs attributed to new construction. Either way, the issue of infrastructure seems to be increasingly categorized as a ‘wicked’ policy problem, Pressman and Wildavsky in 1973 indicated complex policy programs’ ultimate successful resolution were impossible due to, among other issues, lack of goal clarity, information and coordination altogether too difficult to meet. Infrastructure surely seems to fit that category of complexity and wickedness.

Brian Head of the University of Queensland defined wicked policy problems in his 2008 article published in Public Policy as “complex, intractable, and open-ended.” Furthermore, he asked the question as to whether we are developing better ways of addressing such wicked problems. The singular focus of this second article continues where the first article left off — on the impact of technology, as a way of addressing old age infrastructure.

How do we define technology impact? What technologies do we utilize? Assessing the impact of technologies upon U.S. infrastructure includes three distinctive areas of inquiry: productivity, costs and extending the end of product/project lifecycle (EEOPL). A fourth area of impact is emerging as a standard and that would be environmental. To answer the second question, two types of technology classifications would compose the framework for assessing impact: information communications technologies and physical technologies. These technologies will be listed later in this article as we turn the focus back towards the infrastructure categories.

Soon after the first article in this series on Infrastructure and Technology Impact, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) released their updated 2017 American Infrastructure Report Card this past March. As Table 1 indicates below, minimal progress and in most cases, zero progress has been achieved since the last report card in March 2013.

The overall 2017 grade remained the same as 2013: D+. Moreover, the costs to finance the upgrades and/or new construction is estimated to approach $3 trillion by 2020. Conventional wisdom regarding infrastructure posits that the product/project lifecycle and subsequent financing reasonably match up in terms of length of service. However, the infrastructure status is poor and depreciated way beyond its lifecycle. Furthermore, impacts upon environment certainly need to be assessed as infrastructure projects such as roads and dams possess costly implications as evidenced by recent events in California. Meanwhile, productivity increases are required for overall national economic improvement. In other words, is this evidence of a wicked problem? Can technologies provide a collective impact?

In 2001, at the height of the internet bubble, Diewald described in Public Works Management & Policy that technology—and innovation-induced change—“provides opportunities for improvement and that technology developments in materials, electronics, information communications technologies (ICT) can assist in meeting future demand for all infrastructure facilities.” Fast forward to the present state and Frankel and Wachs in their recent 2017 article on infrastructure and governance in Public Works Management & Policy discuss the implications of collective asset management involving more than just money pertaining to infrastructure facilities.

At this point in the discussion, infrastructure, in its present state and age, poses a complex, wicked problem to business, government, and society, collectively. However, technologies have provided solutions at various levels (low, medium, high) of impact upon the four areas (productivity, costs, EEOPL, environment) as well as upon each of the 16 categories listed by the ASCE. These technologies comprise the framework. The technologies represent general areas and are not meant to be all inclusive but are meant to provide a platform for discussion and analysis. The technologies are listed below:

A detailed explanation for each of the 14 technologies listed above, as well as level of impact upon each of the four impact areas, will be juxtaposed to the 16 categories of infrastructure in the forthcoming third article in this series on Infrastructure and Technology.

Finally, the use of such technologies not only possesses impact but may lead to resolving some of society’s most pressing environmental, social and governance issues, such as social equity, intergenerational equity and social responsibility, while unveiling new collective innovations for business and government financing mechanisms such as public-private partnership monetization, and asset pooling, as well as others.

One may argue the wicked problem, that is, the aging and present status as well as costs associated with upgrading and constructing new infrastructure has spawned growth in technologies. Do we have an infrastructure issue in search of a solution? Or, do we have technological solutions in search of a market such as infrastructure?

Author: Daniel G. Bauer is finishing his Doctorate at the School of Public Administration at Florida Atlantic University. Mr. Bauer has an Executive MBA from the College of Business at Florida Atlantic University and a BBA in Finance from University of Toledo. Daniel has 20+ years of professional experience both domestically and abroad. His research areas focus on finding solutions at the confluence of financing, procurement/supply chain, organizational behavior, sustainability, and social responsibility.

Follow Us!