Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Intersectionality: A Framework to Understand Injustice

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Brandi Blessett

March 10, 2015

While reading Creating Capabilities, the author, Martha Nussbuam, posed the question: “Are there groups within the population, racial, religious, ethnic or gender groups that are particularly marginalized or deprived?” In any society, I think the answer is a resounding YES! The chasm between rich and poor, happy or unhappy, healthy or diseased may be minuscule or vast, but there is almost certainly a faction of “others.”

While reading Creating Capabilities, the author, Martha Nussbuam, posed the question: “Are there groups within the population, racial, religious, ethnic or gender groups that are particularly marginalized or deprived?” In any society, I think the answer is a resounding YES! The chasm between rich and poor, happy or unhappy, healthy or diseased may be minuscule or vast, but there is almost certainly a faction of “others.”

When exploring the aforementioned question, one only needs to examine a host of quality of life indicators to recognize the disparity faced by women of color. Statistics from the Office of Minority Health reveal:

- Although breast cancer was diagnosed less frequently in African-American women in 2010, they were 40 percent more likely to die than white women.

- In 2011, African-American women had 23 times the HIV rate of white women, Latino women were 4 times as likely to have AIDS, and American Indians/Alaska Native women were 3 times as likely to be diagnosed with HIV infection as their white female counterparts.

- In 2011, suicide attempts for Latino girls grades 912 were 70 percent higher than for white girls in the same age group.

Such evidence ought to spark outrage about why factions of society are overly represented in some of the most disparaging quality of life indicators monitored. However, in Women, culture & politics, Angela Davis recognized that Black women in particular have a negative social construction in society, which has resulted in punitive domestic policies that have systematically contributed to widespread disparity. This is most evident in declining health outcomes and inadequate educational and employment opportunities, which contributes to political and economic isolation.

Within the workforce, women of color find themselves at the margins regarding bureaucratic representation and pay considerations. Norma M. Riccucci in Public Personnel Management notes that from 1984 to 2004, African-American, Latino and Asian women saw their representations increase by 1.9 percent, 1.4 percent and 0.04% respectively, within the federal civil service. However, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports, “White women ($710) earned 92 percent as much as Asian women ($770), while Black ($599) and Hispanic ($521) earn 78 percent and 68 percent as much as Asians, respectively.” The data reveals the pay differentials experienced by all women, but demonstrates that Black and Latino woman are still financially lagging behind Asian and White women who are positively constructed in society.

A very public depiction of the unfamiliarity and ignorance of intersectionality is best exemplified in Patricia Arquette’s comments at the 2015 Oscars. In her remarks, Ms. Arquette declared “It is time for all women in America and all the men who love women and all the gay people and people of color that we’ve all fought for to fight for us now.” Who exactly is the “us” Ms. Arquette is referring to? It is important to remember that a discussion about unequal pay for women should not differentiate women of color, gay, and transgendered women from being inherently apart of the broader discussion about women’s rights. While Ms. Arquette appeared to be using her platform to address an on-going issue in our society, she simultaneously highlighted her privilege and obliviousness about the lived realities of women of color and LGBTQ individuals.

In fact, bell hooks articulated this best in her book Ain’t I A Woman when she says, “When black people are talked about the focus tends to be on black men; and when women are talked about the focus tends to be on white women.” In this regard, the suffering experienced by women of color is ignored or trivialized based on the inability of colleagues; even those who share the same gender identify, to see the humanity within them. Unfortunately, we find that even within a specific coalition (feminist, LGBTQ, civil rights), race, gender and class hierarchies replicate themselves into the exact superior versus inferior model for which such coalitions seek to undermine.

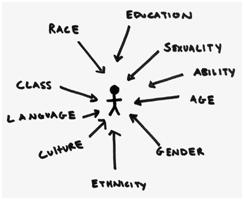

In my judgment, if public administration scholars and practitioners want to become responsive to the needs of the diverse constituency representative of this country, disparity must be examined through the lens of intersectionality as coined by Kimberle Crenshaw, a lawyer and legal scholar. Intersectionality is an analytical framework that seeks to contextualize the multiple oppressions faced by Black women in particular, but women of color more broadly. Crenshaw argued in Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics:

This focus on the most privileged group members marginalizes those who are multiply-burdened and obscures claims that cannot be understood as resulting from discrete sources of discrimination. I suggest further that this focus on otherwise-privileged group members creates a distorted analysis of racism and sexism because the operative conceptions of race and sex become grounded in experiences that actually represent only a subset of a much more complex phenomenon.

As stewards of the public, it is important to understand and effectively respond to issues of inequality and inequity. Therefore, the ability to recognize multiple forms of oppression, as experienced by persons of color, informs holistic solutions about the best ways to combat injustice.

Author: Brandi Blessett is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Policy and Administration at Rutgers University-Camden. Her research broadly focuses on issues of social justice. Her areas of study include: cultural competency, social equity, administrative responsibility and disenfranchisement. She can be reached at [email protected].

(3 votes, average: 4.33 out of 5)

(3 votes, average: 4.33 out of 5)

Follow Us!