Interstate Transportation and The Supremacy Clause: Examining The Road Traveled, Part I

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Sean L. Ziller

November 2, 2019

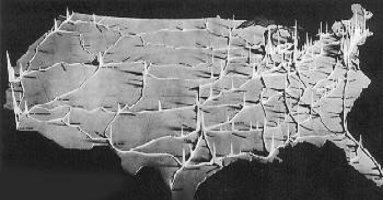

“Illustration of peak traffic volumes based on statewide planning surveys of the 1930s.” – United States Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration

Traveling from Pennsylvania to visit family in the New England area, a few interesting questions popped into my head that I had not broadly contemplated nor even likely considered before. Crossing multiple state lines throughout my journey, I was struck by the notion that the majority of road signs—particularly large interchange signage—were not only standardized regardless of the state or thoroughfare, but, in my view, had seemingly remained that way for decades without significant change imposed. Apart from the traditional regulatory signs, both large and small, that line was on almost every local or state road, including stop signs, no parking markers, and yields. I began an effort to research and reflect on the larger implications of the interstate highway system on our daily lives and, in terms of policy, how we got here.

Despite advancements in personal technology (ex. GPS), traffic signs still play a critical and required role in providing succinct information that helps guide our movements from one region to the next. These signs, strategically dotting the landscape, help to thereby regulate both intrastate and interstate travel while, over time, also directing citizens toward new centers of commerce, residential expansion or other major corridors as they are developed. With all of this in mind, my questions became increasingly more complex the longer I pondered the challenges that I perceived would be inherent to such a regulatory milieu:

- Amidst such a polarized political and regulatory ecosystem, particularly when the federal vs. state dynamic is also considered, why does this area of transit policy seem fairly uncontroversial?

- As these are seemingly federally mandated markings, do states and locales really have no administrative leeway to change how they are displaced? What exactly is the state’s role in these matters?

- And more simply—why, for instance, are interchange advance signs green?

You see them when you travel every day: the green signs designating, for example, an offramp or an upcoming freeway entrance:

Some signs can highlight another upcoming interstate highway or state route, while others indicate cities or towns miles ahead. These signs are so commonplace in the United States that those steeped in transportation policy and administration probably aren’t giving them a second thought. But what level of government and what rule-making body decides how these signs are constructed, posted and maintained? It’s important, with this question in mind, to examine recent history.

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, established 41,000 miles of new highway that would, according to History.com, “Eliminate unsafe roads, inefficient routes, traffic jams and all of the other things that got in the way of, ‘Speedy, safe transcontinental travel.’” In the context of this discussion, it would be particularly important to note the closing words prepared by the President, then delivered by Vice-President Richard Nixon, when announcing the reauthorization of the above Act. In the statement given in front of a conference of state governors, the President acknowledged that federal funding wasn’t enough. Instead, it would be crucial for a, “Properly articulated system of highways,” as reiterated by the Federal Highway Administration, for there to be cohesive coordination between state and federal officials. Eisenhower, via Nixon, explicitly implored the governors in attendance to examine the immense matter at hand and offer their own suggestions as to measures that would meet the 1956 Act’s goals. Ultimately, a multifaceted funding scheme was devised wherein both the federal and state governments, to varying degrees, would fund construction and further maintenance of the Interstate Highway System.

The historical underpinnings of interstate transportation policy in the United States continued to be shaped over the course of the following six decades. Even today, such areas of public administration are still being refined as new administrations, with their own political and policy objectives, occupy the Executive branch. Additionally, the country continually faces persistent challenges in transit operations amidst both increasing urban and rural populations. Drastic shifts in policy were born out of the disparate transit conditions of the early 20th century, refined by standards-setting bodies and further codified by law through legislative decrees such as the Highway Safety Act of 1966. Before that Act’s implementation and since, the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, issued by the Federal Highway Administration, has been periodically updated to reflect proper traffic standards and regulations. As dictated by Congress in the originating Act, should states not adopt pertinent regulations outlined in the MUTCD, funding allocated to them by the federal government could be directly impacted. This document is where we also find the rules stipulating proper sign shapes, markings and colors.

Despite threats of funding decreases directed at noncompliant states, one reason for why such evident policymaking has remained largely uncontroversial, both between states and among them, is the inherent collaborative nature of the standard-setting process. History illustrates where transportation policy experts, at each level of government, have collaborated on devising suitable national safety regulations. However, will such a policy-making process continue to operate as efficiently in attempting to meet emerging 21st century transportation challenges?

To be continued in Part II.

Author: Mr. Sean L. Ziller is a policy analyst / consultant with Conduent State & Local Solutions, Inc. in Philadelphia. He possesses a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science – King’s College (PA) and a Master of Public Administration – Penn State University. All opinions are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer. He can be reached at [email protected].

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

Loading...

Loading...

Interstate Transportation and The Supremacy Clause: Examining The Road Traveled, Part I

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Sean L. Ziller

November 2, 2019

“Illustration of peak traffic volumes based on statewide planning surveys of the 1930s.” – United States Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration

Traveling from Pennsylvania to visit family in the New England area, a few interesting questions popped into my head that I had not broadly contemplated nor even likely considered before. Crossing multiple state lines throughout my journey, I was struck by the notion that the majority of road signs—particularly large interchange signage—were not only standardized regardless of the state or thoroughfare, but, in my view, had seemingly remained that way for decades without significant change imposed. Apart from the traditional regulatory signs, both large and small, that line was on almost every local or state road, including stop signs, no parking markers, and yields. I began an effort to research and reflect on the larger implications of the interstate highway system on our daily lives and, in terms of policy, how we got here.

Despite advancements in personal technology (ex. GPS), traffic signs still play a critical and required role in providing succinct information that helps guide our movements from one region to the next. These signs, strategically dotting the landscape, help to thereby regulate both intrastate and interstate travel while, over time, also directing citizens toward new centers of commerce, residential expansion or other major corridors as they are developed. With all of this in mind, my questions became increasingly more complex the longer I pondered the challenges that I perceived would be inherent to such a regulatory milieu:

You see them when you travel every day: the green signs designating, for example, an offramp or an upcoming freeway entrance:

Some signs can highlight another upcoming interstate highway or state route, while others indicate cities or towns miles ahead. These signs are so commonplace in the United States that those steeped in transportation policy and administration probably aren’t giving them a second thought. But what level of government and what rule-making body decides how these signs are constructed, posted and maintained? It’s important, with this question in mind, to examine recent history.

The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, established 41,000 miles of new highway that would, according to History.com, “Eliminate unsafe roads, inefficient routes, traffic jams and all of the other things that got in the way of, ‘Speedy, safe transcontinental travel.’” In the context of this discussion, it would be particularly important to note the closing words prepared by the President, then delivered by Vice-President Richard Nixon, when announcing the reauthorization of the above Act. In the statement given in front of a conference of state governors, the President acknowledged that federal funding wasn’t enough. Instead, it would be crucial for a, “Properly articulated system of highways,” as reiterated by the Federal Highway Administration, for there to be cohesive coordination between state and federal officials. Eisenhower, via Nixon, explicitly implored the governors in attendance to examine the immense matter at hand and offer their own suggestions as to measures that would meet the 1956 Act’s goals. Ultimately, a multifaceted funding scheme was devised wherein both the federal and state governments, to varying degrees, would fund construction and further maintenance of the Interstate Highway System.

The historical underpinnings of interstate transportation policy in the United States continued to be shaped over the course of the following six decades. Even today, such areas of public administration are still being refined as new administrations, with their own political and policy objectives, occupy the Executive branch. Additionally, the country continually faces persistent challenges in transit operations amidst both increasing urban and rural populations. Drastic shifts in policy were born out of the disparate transit conditions of the early 20th century, refined by standards-setting bodies and further codified by law through legislative decrees such as the Highway Safety Act of 1966. Before that Act’s implementation and since, the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, issued by the Federal Highway Administration, has been periodically updated to reflect proper traffic standards and regulations. As dictated by Congress in the originating Act, should states not adopt pertinent regulations outlined in the MUTCD, funding allocated to them by the federal government could be directly impacted. This document is where we also find the rules stipulating proper sign shapes, markings and colors.

Despite threats of funding decreases directed at noncompliant states, one reason for why such evident policymaking has remained largely uncontroversial, both between states and among them, is the inherent collaborative nature of the standard-setting process. History illustrates where transportation policy experts, at each level of government, have collaborated on devising suitable national safety regulations. However, will such a policy-making process continue to operate as efficiently in attempting to meet emerging 21st century transportation challenges?

To be continued in Part II.

Author: Mr. Sean L. Ziller is a policy analyst / consultant with Conduent State & Local Solutions, Inc. in Philadelphia. He possesses a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science – King’s College (PA) and a Master of Public Administration – Penn State University. All opinions are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of his employer. He can be reached at [email protected].

Follow Us!