Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Unchecking the Box: The Unfulfilled Promise of NCLB

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Andy Plumlee

August 5, 2016

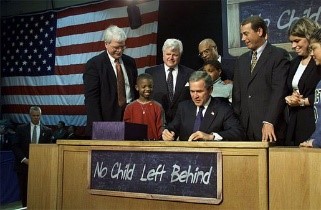

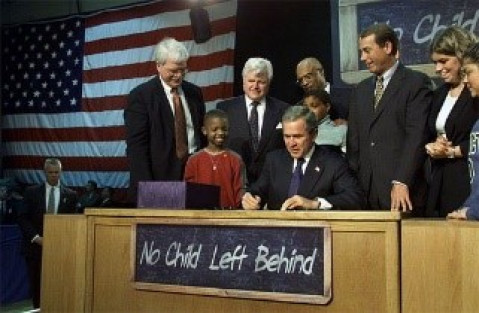

On Jan. 8, 2002, President George W. Bush signed No Child Left Behind (NCLB) into law. NCLB promised to return America’s education system to international competitiveness in fields such as English, math and science. The law inspired hope for America’s educational future and received support from both Democrats and Republicans. Today as the pre-school class of 2002 prepares to be the college freshman class of 2016, one question persists, did NCLB work?

On Jan. 8, 2002, President George W. Bush signed No Child Left Behind (NCLB) into law. NCLB promised to return America’s education system to international competitiveness in fields such as English, math and science. The law inspired hope for America’s educational future and received support from both Democrats and Republicans. Today as the pre-school class of 2002 prepares to be the college freshman class of 2016, one question persists, did NCLB work?

As a parent, my first inclination is to say no. I’m not saying the premise wasn’t sound but rather the application was flawed.

NCLB expanded the federal government’s oversight and funding of public schools and districts that received Title I funding. Sates could opt out of the law but did so at the risk of losing federal aid. Resources would be focused more on student groups who had traditionally struggled to succeed in the American education system, these groups included ESL, special education, minority and low-income students. Using standardized testing, schools and their districts would be able to show students growth and proficiency. So with all the promise, support and initially pledged funds, why do I feel NCLB failed our newest class of high school graduates?

THE TESTING

I graduated high school four years before NCLB was signed into law but this doesn’t mean I wasn’t subjected to standardized testing. Oregon required students to pass two tests, the Certificate of Initial Mastery (CIM) and the Certificate of Advanced Mastery (CAM). I never struggled in school so I was confident the CIM and CAM would be mere formalities. I failed them both. Convinced I would not graduate, I moved with my father to a small California town and attended an alternative learning school the emphasized performance over testing. Instead of memorizing formulas and test answers, my science class took me into the community and collected water samples. Instead of dropping out, I graduated as class valedictorian. I didn’t fit the standardized system. I wasn’t stupid; I just learned differently.

My kid’s educational experience seems different. Their focus appears to be more about passing the tests instead of learning the material. When I asked my son about this, he responded, “what’s it matter, they’re going to pass us anyway.” My son’s right. His educational experience has been more about the standardized test than actual attainment of knowledge. It’s not his fault, I’ve spoken with his schools on many occasions about this and the response was always “but he did quite well on his state testing”

THE PEOPLE

Turns out, his experience might be the norm. A 2012 Gallup Poll found 67 percent of parents with a K-12 student felt NCLB either made no difference (38 percent) or made education worse (29 percent). President Obama shares the feelings of many parents, educators and students according to the White House’s official Web page on education;

“NCLB has created incentives for states to lower their standards; emphasized punishing failure over rewarding success; focused on absolute scores, rather than recognizing growth and progress; and prescribed a pass-fail, one-size-fits-all series of interventions for schools that miss their goals.”

Clearly NCLB is seen as a failure but does the data support the perception?

THE DATA

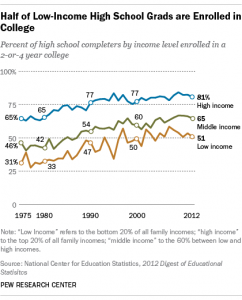

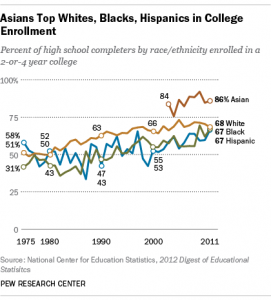

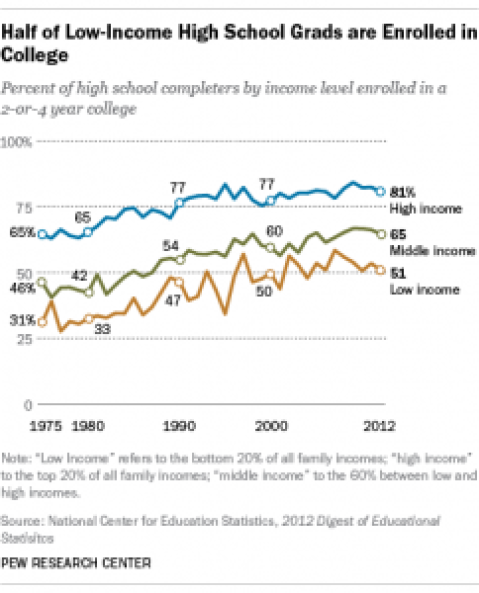

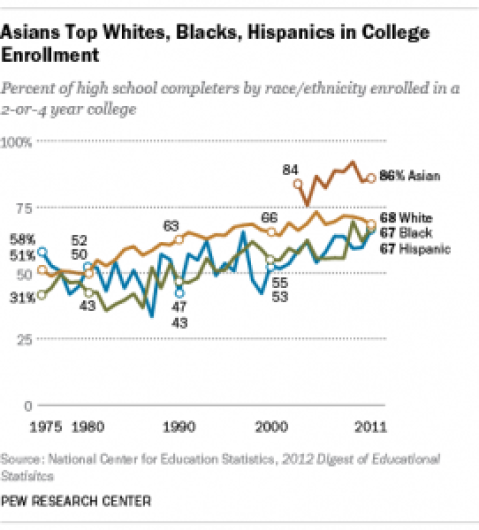

The data surrounding NCLB seems to support what parents, educators and the president perceive. Data from the Pew Institute indicates the gap between white, black and Hispanic students attending college closed to about 1 percent in 2011 (68, 67 and 67 percent respectively, yet data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed a 4.2 percent decline in overall enrollments between 2010 and 2013. While the gap may have closed racially, Pew found lower income students were still 30 percent less likely to attend college compared to their higher income peers. Increased college enrollment for black and Hispanic students is positive but it appears NCLB has done little or nothing to address the disparity caused by a student’s income level. Additionally, the increase is not the result of closing the graduation gap between minority and white students at the high school level.

The National Center for Educational Statistics found that high school graduation rates did increase nearly 10 percent overall between 2002 and 2013. However, when broken down by race for the 2013-2014 school year, there was still a disparity between black (73 percent) and Hispanic (76 percent) students who graduated compared to their white (87 percent) and Asian (89 percent) peers.

NCLB was supposed to better prepare students, especially students of color, for college. The assumption could be made that increasing high school graduation rates of Black and Hispanic students would lead to an increase in college enrollment. This problem with this assumption is graduation and enrollment rates mean nothing if students lack the knowledge required to succeed in college.

President Obama is right, we lost sight of growth and performance. We became focused on passing, absolute scores and graduation rates. Tying funding to test scores forced school districts to emphasize short term memorization over life-long knowledge.

As a result, today’s college student is less prepared for the academic rigors of collegiate life. NCLB failed because education should never be a check the box endeavor.

Author: Andy Plumlee is a dual MBA and MPA candidate in sustainable management at Presidio Graduate School in San Francisco, California. During his time in school, Andy has worked on projects for the City of Berkeley, California, as well as nonprofit and private sector organizations. He can be reached at [email protected] or connect with him through LinkedIn.

Follow Us!