Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

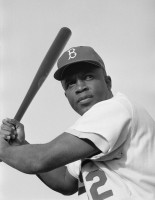

Jackie Robinson and Social Equity in the Public Sector

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Vanessa Lopez-Littleton

April 15, 2016

A few years ago, I wrote an article questioning if diversity and inclusiveness were really possible. Today, I’m still asking myself the same question. When it comes to diversity and inclusiveness, it seems as if many organizations have noble intentions but often fall short in actually achieving their goals.

In this regard, I think the public sector can learn valuable lessons from the life of Jackie Robinson.

As the first black baseball player in the major league, Robinson faced an environment ripe with hostility and negativity. On and off the field, he endured countless taunts, threats and invectives. Not because of his performance, but because of the color of his skin. Although Robinson’s life presents many opportunities for personal and collective growth, the following are two important lessons to support social equity and diversity efforts in the public sector.

As the first black baseball player in the major league, Robinson faced an environment ripe with hostility and negativity. On and off the field, he endured countless taunts, threats and invectives. Not because of his performance, but because of the color of his skin. Although Robinson’s life presents many opportunities for personal and collective growth, the following are two important lessons to support social equity and diversity efforts in the public sector.

First, Robinson’s experience as the first black in Major League Baseball on April 15, 1947, predates Martin Luther King, Jr., the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. But Robinson’s story is more than a tale of a tremendous athlete overcoming monumental odds. Robinson’s story is also about an American society learning to accept racial differences in spite of its past. At the start of his career, Robinson’s bore the brunt of personally mediated racism that included social exclusion, stigmatization, unfair treatment, harassment and structural barriers that legitimized many of the insults he endured. By the end of his career, Robinson had won over the heart and soul of many Americans, paving the way for countless others.

Today, blacks continue to bear the burden of a society that for centuries relegated them to second class citizenship status. The blatant acts of discrimination and racism evident before 1964 have been replaced with institutional forms of oppression or institutionalized racism. These structural barriers act as obstacles that—without deliberate acknowledgement and effort to overcome them—will become an enduring feature of American society. One of the most challenging aspects of institutionalized racism is the failure of people in positions of power or privilege to acknowledge its existence.

Just as Robinson had to show up on the field, time and time again, we too must be vigilant in our efforts to promote diversity and inclusiveness in the public sector. Recognizing that in order for equality to exist in America, we must begin by identifying structural racism within every area of the public sector and purposefully invest in efforts to promote social equity as a core American value.

Second, in 1947 when Robinson took the field, no one would deny the existence of racism and discrimination in American culture. In fact, racism and discrimination were open and publicly supported by policies and governments. Today, racism has taken on another form where it is embedded in our systems of practice but evidenced in a broad range of disparate outcomes. But racism can also be seen on the individual level where people, masked by the Internet, freely hurl racist insults on social media platforms.

In thinking about Robinson and his impact on society, one would be remiss not to acknowledge the countless others for their role in giving Robinson the chance to play. In particular, Branch Rickey, club president and general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who is inspirational for his efforts to diversify the game as well as his astuteness in starting a “farm system” to provide black players with a chance to gain experience and support in their formative years. As blacks tend to have fewer mentors and role models, Rickey’s approach to nurturing young players is a good strategy to promote the professional growth and development of future black leaders and managers in the public sector.

When viewed this way, these two aspects of Jackie Robinson’s life serve as action steps toward the ASPA Code of Ethics and the principle of social equity by strategically working to reduce “unfairness, injustice and inequality in society.”

Author: Vanessa Lopez-Littleton, Ph.D., RN, is an assistant professor in the Department of Health, Human Services and Public Policy at California State University, Monterey Bay. Her research focuses on social equity, cultural competence, and racial and ethnic health disparities.

(5 votes, average: 4.80 out of 5)

(5 votes, average: 4.80 out of 5)

Pingback: Jackie Robinson, Lessons for the Public Sector | Stirring Up Trouble by DrVLoLil