Lagging and Leading Indicators of Government Performance Management

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Prajapati Trivedi

February 9, 2018

All performance indicators can be broadly divided into two categories – lagging indicators and leading indicators. Lagging indicators measure the current results of our past efforts, whereas leading indicators measure the future results of our current efforts. For example, the level of tourism in a country is a lagging indicator. Today’s tourism in any country is usually a result of many years of (past efforts) by government and others to promote tourism. Similarly, today’s tourism promotion campaigns by a country are likely to yield most of their results in the future. Typically, therefore, lagging indicators deal with “outcomes” and leading indicators deal with “outputs.”

All performance indicators can be broadly divided into two categories – lagging indicators and leading indicators. Lagging indicators measure the current results of our past efforts, whereas leading indicators measure the future results of our current efforts. For example, the level of tourism in a country is a lagging indicator. Today’s tourism in any country is usually a result of many years of (past efforts) by government and others to promote tourism. Similarly, today’s tourism promotion campaigns by a country are likely to yield most of their results in the future. Typically, therefore, lagging indicators deal with “outcomes” and leading indicators deal with “outputs.”

This implies performance management of a government department based on lagging indicators is not only unfair and misleading, but also counterproductive. It is possible the current managers of the department are taking actions that will be detrimental to the desired long-term goals of the department and yet they are being rewarded based on a lagging indicator. Hence, persons charged with designing a performance management system should first and foremost make sure that they are not using only the lagging indicators.

Static versus Dynamic Indicators

Leading indicators of performance can be, in turn, further subdivided into two categories – those measuring “static” performance and those measuring “dynamic” performance. Static performance indicators measure the results of our efforts in one accounting year. For example, results achieved by a government department by living up to its commitments for timely delivery of public services in a Citizen Charter would be an example of static efficiency. The key characteristic of a “static” indicator is that all costs (increased effort) and most of the benefits (increased citizen satisfaction) associated with the action are delivered in the same accounting year.

Dynamic indicators of performance, on the other hand, involve incurring the cost in one calendar year and benefits accruing in future years. Human Resource Development (HRD) is a common example used to illustrate this point. The cost of training and capacity building is incurred immediately, but benefits flow over time. That is the reason why HRD is the first things to go when budgets are tight. The negative consequences of cutting HRD are likely to be felt in the future when the manager in question has long been promoted and moved on to managing other units.

Unfortunately, most government performance management systems tend to focus on static efficiency indicators because they are:

- easier to measure

- easier to implement

- better understood by common man

- perceived to have higher political returns

Meta Criterion

A government performance management system must not only be fair to the managers but also fair to the country. By ignoring dynamic efficiency aspects of performance, most systems do not meet this “fairness” standard.

A performance management system is “fair” to managers when it measures all areas within the “control” of managers. For example, such a fair system adjusts for exogenous factors and force majeure, the unknown unknowns. A “fair” system also counts all the contributions of the management accurately. Many public managers instinctively want to do the “right” thing. They know they are not only employees of the government department but, as citizens, also a shareholder in the government. They want to have a long-term impact on the public institutions. A government performance management system that focuses on static efficiency alone therefore ignores the desire of the public managers to do the “right” thing. Hence, it is unfair to them.

A performance management system is “unfair” to the country when a manager can look good at the cost of long-term health of the organization. This is exactly what happens when a system design ignores dynamic efficiency aspects of performance.

Private sector has been aware of this important distinction for some time. This distinction lies at the heart of the Balanced Score Card approach. It tries to judge performance based on a combination of long-term and short term parameters.

NAPA White Paper

A holistic approach to performance management is also catching on in government. Its value is most vividly captured by a recent White Paper by the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) entitled, “On Strengthening Organizational Health and Performance in Government.” This report cites the following definition of “organizational health” in the private sector by McKinsey & Company: “capacity to deliver—over the long term—superior financial and operating performance.” This definition emphasizes the multi-dimensional character of organizational health; dimensions include leadership, motivation, innovation and learning, culture, organizational climate, risk management, among others.

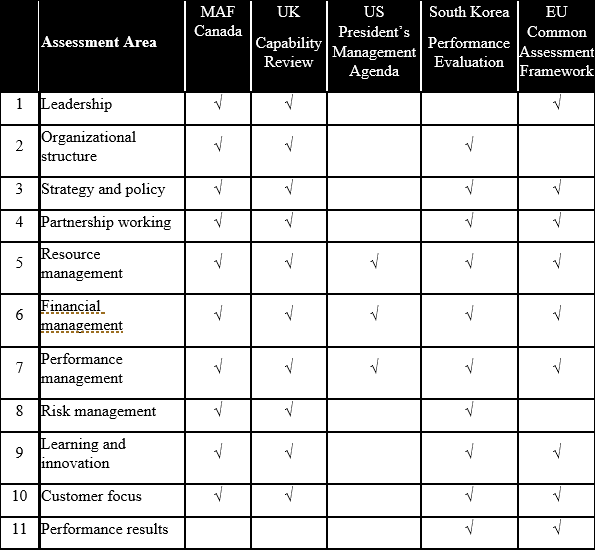

Many Commonwealth countries are pioneers in applying this holistic approach to performance in government. It started with UK capability reviews and was adopted by Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Table below presents an international comparison of leading Government Performance Management Systems prepared by the UK’s National Audit Office in 2009.

It is clear from the above table that while there is greater realization about the holistic approach to government performance management, there is insufficient consensus on the concept of what constitutes “holistic” approach. It is, therefore, time to develop a consensus on generally accepted performance management practices.

Author: Prajapati Trivedi is Director in Commonwealth Secretariat with the responsibility for the Economic, Youth, and Sustainable Development (EYSD) Directorate. Till recently he was a Senior Fellow (Governance) and Faculty Chair for the Management Program in Public Policy (MPPP), Indian School of Business (ISB). From 2009-2014 he served as chief performance officer for the Government of India. A Fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA), Washington, DC, he continues to be a Visiting Faculty, Harvard Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University and Visiting Fellow, IBM Center for the Business of Government, Washington, DC. He can be reached at: [email protected]

(2 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

Loading...

Loading...

Lagging and Leading Indicators of Government Performance Management

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Prajapati Trivedi

February 9, 2018

This implies performance management of a government department based on lagging indicators is not only unfair and misleading, but also counterproductive. It is possible the current managers of the department are taking actions that will be detrimental to the desired long-term goals of the department and yet they are being rewarded based on a lagging indicator. Hence, persons charged with designing a performance management system should first and foremost make sure that they are not using only the lagging indicators.

Static versus Dynamic Indicators

Leading indicators of performance can be, in turn, further subdivided into two categories – those measuring “static” performance and those measuring “dynamic” performance. Static performance indicators measure the results of our efforts in one accounting year. For example, results achieved by a government department by living up to its commitments for timely delivery of public services in a Citizen Charter would be an example of static efficiency. The key characteristic of a “static” indicator is that all costs (increased effort) and most of the benefits (increased citizen satisfaction) associated with the action are delivered in the same accounting year.

Dynamic indicators of performance, on the other hand, involve incurring the cost in one calendar year and benefits accruing in future years. Human Resource Development (HRD) is a common example used to illustrate this point. The cost of training and capacity building is incurred immediately, but benefits flow over time. That is the reason why HRD is the first things to go when budgets are tight. The negative consequences of cutting HRD are likely to be felt in the future when the manager in question has long been promoted and moved on to managing other units.

Unfortunately, most government performance management systems tend to focus on static efficiency indicators because they are:

Meta Criterion

A government performance management system must not only be fair to the managers but also fair to the country. By ignoring dynamic efficiency aspects of performance, most systems do not meet this “fairness” standard.

A performance management system is “fair” to managers when it measures all areas within the “control” of managers. For example, such a fair system adjusts for exogenous factors and force majeure, the unknown unknowns. A “fair” system also counts all the contributions of the management accurately. Many public managers instinctively want to do the “right” thing. They know they are not only employees of the government department but, as citizens, also a shareholder in the government. They want to have a long-term impact on the public institutions. A government performance management system that focuses on static efficiency alone therefore ignores the desire of the public managers to do the “right” thing. Hence, it is unfair to them.

A performance management system is “unfair” to the country when a manager can look good at the cost of long-term health of the organization. This is exactly what happens when a system design ignores dynamic efficiency aspects of performance.

Private sector has been aware of this important distinction for some time. This distinction lies at the heart of the Balanced Score Card approach. It tries to judge performance based on a combination of long-term and short term parameters.

NAPA White Paper

A holistic approach to performance management is also catching on in government. Its value is most vividly captured by a recent White Paper by the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA) entitled, “On Strengthening Organizational Health and Performance in Government.” This report cites the following definition of “organizational health” in the private sector by McKinsey & Company: “capacity to deliver—over the long term—superior financial and operating performance.” This definition emphasizes the multi-dimensional character of organizational health; dimensions include leadership, motivation, innovation and learning, culture, organizational climate, risk management, among others.

Many Commonwealth countries are pioneers in applying this holistic approach to performance in government. It started with UK capability reviews and was adopted by Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Table below presents an international comparison of leading Government Performance Management Systems prepared by the UK’s National Audit Office in 2009.

It is clear from the above table that while there is greater realization about the holistic approach to government performance management, there is insufficient consensus on the concept of what constitutes “holistic” approach. It is, therefore, time to develop a consensus on generally accepted performance management practices.

Author: Prajapati Trivedi is Director in Commonwealth Secretariat with the responsibility for the Economic, Youth, and Sustainable Development (EYSD) Directorate. Till recently he was a Senior Fellow (Governance) and Faculty Chair for the Management Program in Public Policy (MPPP), Indian School of Business (ISB). From 2009-2014 he served as chief performance officer for the Government of India. A Fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA), Washington, DC, he continues to be a Visiting Faculty, Harvard Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University and Visiting Fellow, IBM Center for the Business of Government, Washington, DC. He can be reached at: [email protected]

Follow Us!