Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Lessons from the Fight to End Veteran Homelessness

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Kate Voshell

December 20, 2016

When Veterans Commons opened in San Francisco in 2012, it provided housing for 75 formerly homeless veterans along with a range of supportive services for residents and the larger community. This project was made possible by an innovative use of Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing vouchers in which benefits usually allocated to individuals for use toward rent were bundled together and provided on a “project-based” basis. Since 2009, innovative programs for ending Veterans homelessness have been very successful in providing stable housing and providing lessons for government in tackling a wide range of problems.

Background

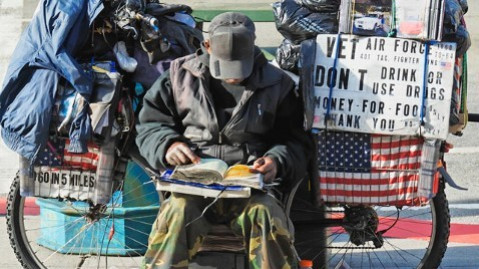

Homelessness is pervasive among veterans who are disproportionately represented among the homeless population. In addition to employment barriers such as increased instances of mental illness and substance abuse, veterans tend to physically age faster than the general population and lack supportive family structures to rely on during hard times. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates that 1 in 10 homeless individuals is a veteran. In 2009 that translated to approximately 73,367 individuals. In order to step up efforts to serve those who served our country, the White House and the Veterans Affairs (VA) announced a joint goal to end veteran homelessness.

Empowering Cities to End Veteran Homelessness

In addition to reforming federal veterans housing programs to be more effective, such as the addition of project-based funding described above, the White House and the VA sought to impact service at the municipal level by creating the Mayors Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness. This program provides resources and promotes reforms to maximize the provision of housing opportunities.

One such innovative program is the HUD-funded Rapid Results Housing Boot Camps. This effort, led by the Rapid Results Institute, brings mayors of multiple cities together with national and local leaders to set “unreasonable” goals for addressing veteran homelessness and propose 100-day plans to achieve them. The boot camps encourage cities with different local conditions to brainstorm around a common goal, getting fresh eyes on intransigent barriers. Strategies have included streamlining paperwork, providing one-stop access points for veterans and incentivizing caseworkers to address the most vulnerable populations.

Philadelphia: A case study

In 2013, Philadelphia was struggling to house a homeless veteran population that had skyrocketed 46 percent between 2009 through 2013. Philadelphia participated in the Rapid Results Housing Boot Camp in August 2013. Among the outcomes were a coordinated effort with HUD-VASH to reduce processing times for applicants and the formation of the Philly Vets Home 2015 team, which was tasked with coordinating resources and tracking progress toward the city’s 100-day goals.

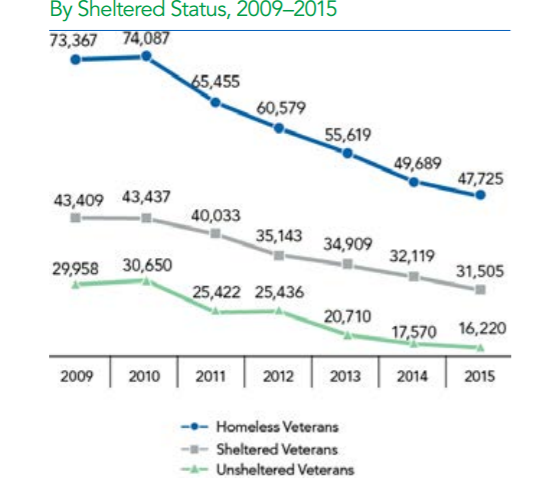

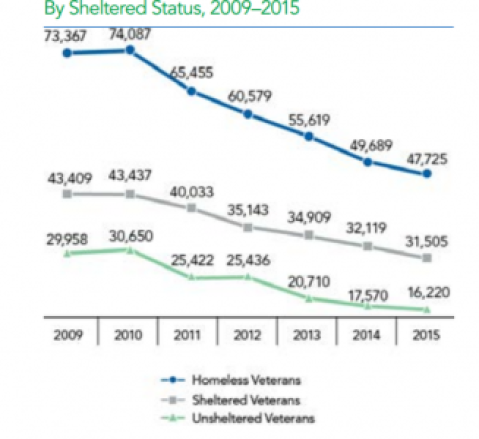

A particularly effective effort by the Philly Vets Home 2015 team was the creation of a “master list” of local homeless veterans compiled from separate databases kept by the Veteran Administration and other nonprofit organizations. This list allowed the organization to track and coordinate efforts on behalf of veterans with “laser-like” focus. Through the coordinated efforts of service providers and funders, Philadelphia housed 1,400 veterans in the span of 2.5 years. In December 2015, HUD, the VA, and the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness declared that Philadelphia had ended veterans’ homelessness. According to the Mayors Challenge to End Homelessness website, 29 cities and 3 states have achieved that goal. Nationwide, HUD reports that the number of homeless veterans has dropped to 47,725, just 65 percent of what it was at the inception of this effort seven years ago.

Point in Time Estimates of Homeless Veteran by Sheltered Status

Point in Time Estimates of Homeless Veteran by Sheltered Status

source

Lessons for other “wicked problems”

In the article “How Social Innovation is Helping Veterans,” author Ron Ashkenas discusses the Rapid Response Boot Camp model and suggests that the success of this approach derives from “mobilizing the ecosystem” for innovation. As he points out, “[m]ost organizations are structured to perform today’s work, and not designed to do something radically different.” Therefore, innovation must come from completely reconfiguring “resources and assets.”

Cities, faced with ongoing budget cuts and increasing service demands may find that “mobilizing the ecosystem” can help them confront a wide range of so-called “wicked problems.” Organizations such as C40 are spearheading similar efforts to harness municipal collaboration and problem-solving to attack climate change. But there are other issues to tackle: multigenerational poverty, dwindling economic opportunity and educational disparity. As we fail to see federal solutions to these problems materialize, it falls on local governments to be the change we want to see in the world.

Author: Kate Voshell is an MPA candidate at Presidio Graduate School. She plans to leverage her 14 years as an architect specializing in multi-family affordable housing into a career shaping policies incentivizing sustainable and socially equitable community urban development.

source

source

Jimmy R. Aycart

December 20, 2016 at 8:04 pm

since the veterans are the greatest group of civil servants, ASPA should help to the many others that who knows where they are today. As a Vietnam veteran and as MPA and ASPA member lets try something good. It is cold outside.