Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Lying in Public Life

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Terry Newell

September 13, 2016

On March 12, 2013, James Clapper, Director of National Intelligence, was asked by Sen. Ron Wyden of the Senate Intelligence Committee, “Does the National Security Agency (NSA) collect any type of data at all on millions or hundreds of millions of Americans?” “No, sir,” Clapper replied.

On March 12, 2013, James Clapper, Director of National Intelligence, was asked by Sen. Ron Wyden of the Senate Intelligence Committee, “Does the National Security Agency (NSA) collect any type of data at all on millions or hundreds of millions of Americans?” “No, sir,” Clapper replied.

On June 5, 2013, articles based on documents provided by Edward Snowden showed the NSA was doing just that. Shortly thereafter, Clapper wrote Intelligence Committee Chairwoman Diane Feinstein and said, “My response was clearly erroneous – for which I apologize.” He later told MSNBC’s Andrea Mitchell, “I responded in what I thought was the most truthful, or least untruthful manner, by saying ‘no.'” Clapper argued his testimony was not a lie because it all hinged on what the word “collect” means. He also claimed he was caught in a situation where he was asked in a public forum about a classified data collection system. Some accused Clapper of perjury and demanded he resign.

When Americans believe public servants are lying, trust in government is the first casualty. Yet, lying is a problem that goes well beyond national security situations (where sometimes lies are required to protect lives and secrets). In a 2007 National Government Ethics Survey, nearly 30 percent of public servants reported observing lying to employees and the public in their agencies. A 2015 study by the Army’s Strategic Studies Institute found officers admitted lying to headquarters staff, reporting completion of tasks they lacked the resources to accomplish and that superiors knew they were being lied to but let it pass. The study’s authors called this “mutually agreed deception.”

What is a lie?

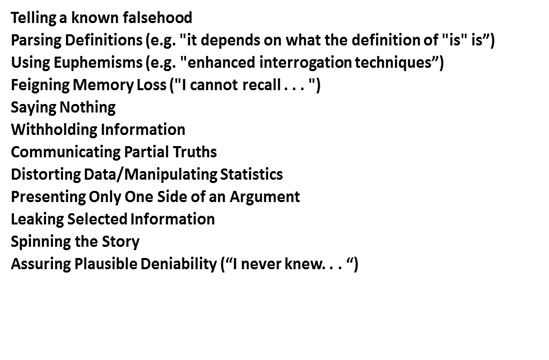

To test your “Pinocchio” sensitivity, which of the actions below is a lie?

In my work with government executives, everyone agrees that the first one is a lie. There’s not much agreement after that. People admit, often sheepishly, to using many of these techniques, but they insist they didn’t lie.

How would you feel if a government employee used one of these in answering your question? If it would bother you, you can see that “lying” is not as simple as applying a legal test of “the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.” More importantly, if we aren’t clear on what a “lie” is, we should expect a lot of ethical slipperiness.

Why do people lie?

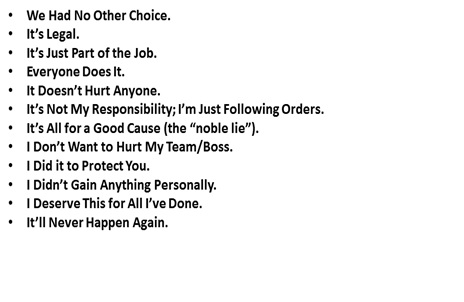

Let’s consider five common reasons. First, people may lie because they think they must, to protect the nation and its secrets. But this can be easily overused. Second, as we’ve seen, public servants lie but don’t think they are doing so. Third, people lie because of job, peer or supervisory pressures, as the Army case illustrates. Fourth, people lie because they can rationalize it and there are lots of rationalizations (see below).

Fifth, people lie because of moral licensing. Think of it this way. You are a moral person; you act ethically in almost every case. When confronted with a situation in which lying is really tempting, you give yourself permission just this one time. It’s like you have made so many deposits in the bank of truthfulness that one withdrawal is no big deal.

Social psychologist Dan Ariely posits a similar logic in his book, The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty. His research found that people will only lie up to the point that they cannot reconcile it with their self-concept, even if they had no chance of being caught.

How can we be more truthful?

Knowing the techniques used to evade truth-telling and the rationalizations can help us be more honest. But that’s not always enough.

- Use reminders: When reminded of their obligation to tell the truth, people may be less likely to lie. Retaking the oath of office or signing forms that testify to our veracity in a given document (e.g., a financial disclosure form), report or action can be useful.

- Reward truthfulness: Leaders can emphasize the importance of honesty by setting an example, such as creating honesty as a core value, rewarding truthfulness and punishing lies.

- Decrease the distance between the actor and the act: It’s easier to lie if those lied to are separated, geographically or organizationally.

- Prevent lying from becoming socially acceptable: In March 2013, Beverly Hall, the former superintendant of Atlanta’s schools, and 34 others were indicted on multiple charges connected to changing students’ answers on standardized tests to produce higher scores. One person could not have succeeded in doing this alone, but when a like-minded group formed, it became more socially acceptable.

- Counter rationalizations: Ask unbiased others to check your reasoning and justification before you act.

- Search for ways to be more truthful: Don’t ask “am I lying?” That can be hard to determine. Ask “what can I say to be more truthful?”

Author: Terry Newell is president of his training firm, Leadership for a Responsibility Society and is the former dean of faculty of the Federal Executive Institute. His latest book is titled, To Serve with Honor: Doing the Right Thing in Government. Email: [email protected].

Follow Us!