Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Mind Your Blind Spots: Racial Equity and Transportation Policy

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Grant E. Rissler

July 31, 2019

In the 20th century, cars and car ownership became almost universal in America, reshaping where and how people lived. But ignoring how this car friendly system can maintain and worsen racial inequity is a dangerous and too often unrecognized blind spot in transportation policy.

If you’ve given The Bridge, ASPA’s weekly e-newsletter, a close read recently, you know that the journal Public Integrity issued a call for papers (abstracts due Aug. 15) for a special issue on using Critical Race Theory (CRT) to promote a race-conscious public administration. Race and racism, the call for papers notes, “Are rarely explicit in public administration scholarship and praxis,” resulting in analyses that ignore how racism created and continues to maintain systems that oppress people of color and policies that are paralyzed by these blind spots. It fails to address root cause issues.

Shortly after reading the call for papers, I came across law professor Gregory Shill’s recent article in the Atlantic that outlines numerous ways that the United States legal system privileges car drivers over others. In addition to politically popular spending on the maintenance and expansion of roads and bridges, the article highlighted ways I’d never thought about that policies and systems make Americans, “Car dependent by law.”

- Parking quotas attached to new house and commercial construction mean as much of a third of land area in some United States cities is dedicated to parking.

- United States car safety regulations only require manufacturers to mitigate harm to car occupants, not to those outside—taller and heavier SUVs are safer for passengers and deadlier to cyclists and pedestrians.

- State minimum requirements for bodily-injury insurance coverage are often far below the likely medical costs faced by a pedestrian or cyclist who is hit by a car.

Shill argues for increased changes to bring greater equity to non-drivers in United States society, including dropping exclusionary zoning regulations that require large lots for new housing (and make cars a necessity), Vision Zero design standards and others. But nowhere in his Atlantic article (and only briefly in his underlying law review article) does Shill examine whether this preferred status for drivers of cars has a disproportionate impact on people of color. This oversight highlights why a critical race lens is essential in public administration.

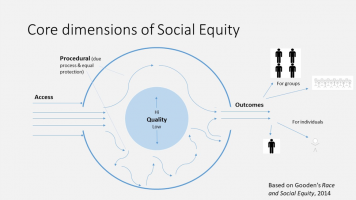

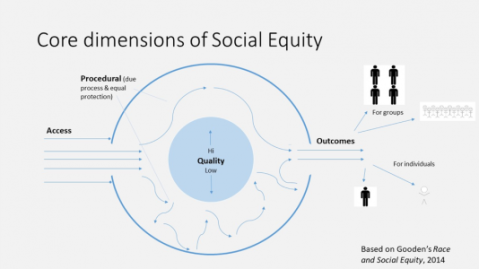

In terms of the four core dimensions of social equity articulated by Susan Gooden and summarized in the visual below, having a car is a clear equity of access issue. But for anyone who has tried to show up looking crisp for an interview via bike or on foot on a 90+ degree day, not having a car can lead to differences in the quality of services and the outcomes received.

(in)Equity of access.

The National Equity Atlas compiles data on car access by race/ethnicity. The overall numbers for the United States are striking —while 9.1 percent of United States households overall make do without access to a vehicle, that number drops to 6.1 percent for whites and rises to 11.3 percent for Asians, 12 percent for Latinos and 19.7 percent for blacks. In short, nationwide black households are more than 3 times more likely to lack access to a vehicle. Though not highlighted by Shill, all the legal systems that favor drivers over non-drivers are also disproportionately favoring whites over people of color.

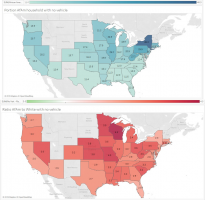

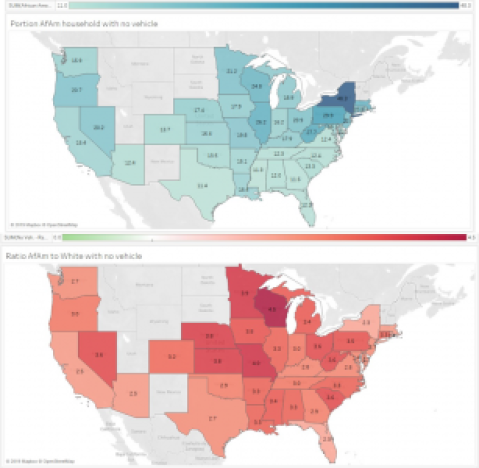

I was curious to see how such rates compared from state to state, which the Atlas does not provide, so I pulled the relevant car access data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017 American Community Survey (ACS) 1-Year Estimates. Because many states had insufficient population of Asians or Native Americans to allow estimates, I chose to focus my mapping analysis on differences between Whites and African Americans.

The maps below (interactive versions available here) show the portion of African American households with no vehicle (top chart) and the ratio of the percentage of African Americans without a vehicle to the percentage of whites (bottom). States with darker shades of blue signify higher portions of African Americans without a vehicle (highest in New York at 48.3 percent) and darker shades of red indicate a higher ratio of African Americans to Caucasians without car access (highest in Wisconsin where African Americans are 4.5 times more likely to have no vehicle access).

Insights emerging from this analysis include:

- Southern states tend to have lower portions with no access to vehicles, perhaps because the African American population is less concentrated in urban areas in these states.

- In every state where data is available, African Americans are at least twice as likely than whites to live without access to a vehicle and in 25 states they are three times or more likely. Only the District of Columbia comes somewhat close to equity at a ratio of 1.4.

Equity in quality of services and outcomes

As noted in a prior column, such a lack of vehicle access has important ramifications for access to healthy foods, in turn leading to worse health outcomes for blacks than for whites. One can easily imagine that the same would hold true in relation to many other services, from employment and recreation opportunities to shopping for non-food items and governmental services.

Conclusion

In short, though not highlighted by Shill, policies that continue to privilege those with car access are bound to also worsen measures of racial equity. Those who do not pay attention to this fact in setting transportation policy are ignoring a dangerous blind spot.

Author: Grant Rissler is a full-time parent and an affiliate faculty member in the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU). He edits the Governance Matters section of State and Local Government Review and is the current secretary of the ASPA Section on Democracy and Social Justice (SDSJ). His broad research focus is social equity and peacebuilding with particular interest in local government responsiveness to immigrants. Grant can be reached at [email protected].

Burden S Lundgren

August 11, 2019 at 3:59 pm

I live in Norfolk VA. This column reminded me of the time my (white) son acted as free cab service to his black co-workers on a summer construction job. Without this transportation, his co-workers would either have to spend hours on public transportation to get to the job or stop working. I’m sorry to say I don’t know what happened to those workers after my son went back to college – but I hope they all learned something from each other – I know my son did.