Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

On My Desk: The (Ignored) Philanthropic Impulse of Immigrants and Migrants in the U.S.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Grant Rissler

October 4, 2024

The newest issue of Administrative Theory & Praxis includes an article by Susan Appe highlighting the fact that, while immigrants are often overlooked as donors and philanthropists, there are myriad examples of immigrant-organized philanthropy, including the efforts of numerous diaspora giving initiatives to support efforts in a homeland. The author notes this picture of immigrants in the United States is a needed contrast to the frequent portrayal in U.S. society of immigrants as “recipients” or even “takers” of resources.

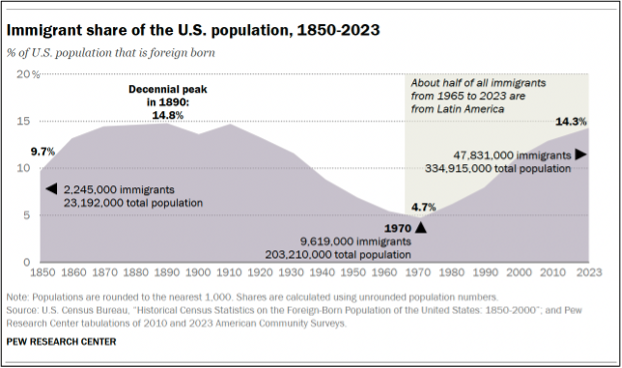

In a September 27th post for the Pew Research Center, Mohamad Moslimani and long-time immigration scholar Jeffrey Passel highlight a 1.6 million person increase in the U.S. foreign born population in 2023, the largest single year jump since 2000. This brings the U.S. immigrant population to 14.3 percent of the total, or about 1 in 7 residents of the United States, not far from the all-time decennial high set in 1890, when it stood at 14.8 percent (see graphic below).

The impact of immigrants is both well-documented while also being the subject of significant political contestation. The American Immigration Council provides a Map the Impact interactive tool (based on 2018 data) to understand the state and local economic impact of immigrants and also recently highlighted in a June press release that in 2022, roughly one-quarter of STEM workers, agricultural workers, construction industry workers and health aides are immigrants. Additionally, “immigrant households paid nearly one in every six tax dollars collected by federal, state and local governments.”

Insights on the (Ignored) Philanthropic Impulse of Immigrants

Despite this clear economic impact, Appe highlights the fact that in the public administration literature as well as the literature on philanthropy in the U.S., giving by immigrants and the role of immigrant organizations is largely unstudied or ignored, while immigrants frequently show up in news stories and the academic literature as recipients of nonprofit or government services and immigration is often defined as a policy issue or problem. Citing a systematic literature review on third sector organizations and migration by Garkisch et al., Appe notes that the literature reflects nonprofits 1) providing basic services to immigrants, 2) developing the capacities of immigrants, 3) amplifying the voice of immigrants and 4) conducting research about/with immigrants but does not capture many instances of where immigrants act as philanthropic givers and leaders. Appe notes on page 305 that studies like hers, which examines philanthropy of Mexican diaspora “hometown associations (HTAs), not only contribute to “understanding philanthropy among different economic groups” but “can be an aid to counter the negative stereotypes related to migration.”

Further in the article, Appe documents the work of HTAs with links to the northern Zacatecas region of Mexico—how they have coordinated the generation (through fundraisers celebrating their culture), collection and giving of resources to pave roads, improve water quality and fund cultural spaces within the “hometown” areas while also encouraging youth within the diaspora to maintain connections to their heritage. Appe concludes (pg. 316) “my research finds examples of immigrants and migrants as givers, not takers. They are nonprofit leaders in what can be considered ‘migrant civil society’ with binational and transnational implications.”

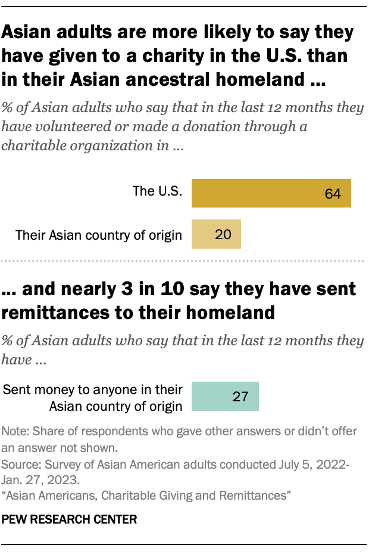

Certainly the philanthropic activity documented by Appe’s research is far from unique. Additional research by the Pew Research Center highlights that the members of the pan-Asian community in the United States, which is more than half foreign-born, shows strong charitable giving, with 64 percent reporting volunteering or donating to a charitable organization in the last year (see box at right). My own research and personal experiences have brought me into contact with diasporas ranging from Chinese to Estonian that formed non-profits to organize cultural and language schools that preserve their heritage and introduce other Americans to it.

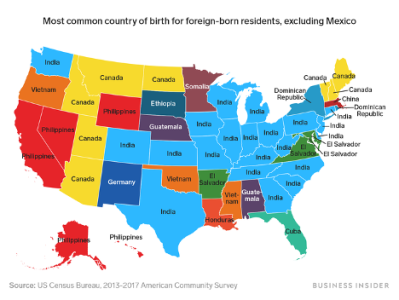

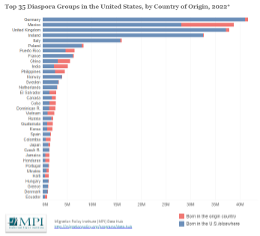

Reflecting on the range of immigrant diasporas in the United States additionally points to these communities as having wide influence. The graphic below, developed by the Migration Policy Institute, is taken from their interactive display of the top 35 diaspora groups in the United States, as of 2022. In the chart, the red portions of each bar represent the portion of the diaspora community who were born in the country of origin while the blue bar indicates members who were born in the United States. The more than 41 million German-Americans are the largest diaspora, and the one from which my own family roots emerge, followed closely by the almost 38 million Mexican-Americans. In addition to the communities with origins in China, India and the Philippines, a number of the country origins with the highest percentage of foreign born members are located in Latin America (e.g. El Salvador, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Colombia). The Business Insider map of the U.S. shows which is the most common country of birth for foreign born residents if you exclude those of Mexican origin (who are the most populous in 36 states). Both are reminders of the diversity of the immigrant communities in the U.S.

Relevance to Public Administrators

As Appe notes, public administration scholars often focus on immigration as an issue facing society, or even as one of many “wicked problems” (meaning ones that are difficult to solve and evolving constantly). This framing plays into a conception where well-meaning public administrators may adopt what Stout and Love, in their article Exposing and Dismantling White Culture in Public Administration term “power-for” strategies that try to solve problems for others while not developing authentic “power-with” collaborations that preserve the agency of immigrants and recognize the resources held by immigrant communities. The work of both Appe and Stout and Love are reminders to public administrators of the potential strength that could emerge from focusing efforts on developing “power-with” collaborations.

Conclusion

Appe’s article is a crucial reminder to public administrators and U.S. society more broadly that immigrants and immigrant-led organizations are clearly sources of philanthropy that make important impacts within the United States and in their own country of origin.

Author: Grant Rissler is Assistant Professor of Organizational Studies at the School of Professional and Continuing Studies, University of Richmond (VA). He serves on the editorial board of Administrative Theory & Praxis (ATP) and focuses his research on social equity and peacebuilding with particular interest in local government responsiveness to immigrants. The “On My Desk” series of columns, beginning in July 2024, intentionally highlights the insights of one or more articles published in ATP in relation to a current debate or event. Grant can be reached at [email protected].

Follow Us!