Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Preparing and Budgeting for Resilience in the Urban Environment

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Daniel Hummel

January 29, 2016

The concept of resilience is replacing sustainability as the new prerogative for cities around the world, particularly as the impacts of climate change become apparent on many vulnerable cities. Resilience has been defined in different ways. In a 2011 report titled, “‘Financing the Resilient City’ for ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability,” Jeb Brugmann defined it as an effort to provide predictable performance for benefits and returns for users and investors in an urban environment. He considered the term to be more comprehensive and proactive than sustainability or adaptation. He noted that resilience is about mitigating risks that come from catastrophes such as natural and man-made disasters or system-wide inefficiencies.

Lawrence Vale, in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT, wrote that resilience has many different interpretations across many fields in his article, “The politics of resilient cities: whose resilience and whose city?” In the planning profession, it is the ability to respond to systemic threats. Systemic threats as described by Brugmann are inefficiencies in the urban system such as with electricity, water and transportation. Despite this description, the typical concern with resilience is the ability to sustain and recover from catastrophes. Planning for potential disasters or systemic inefficiencies can be quite expensive and politically unpopular for a number of reasons, while responding to catastrophes is more politically expedient.

According to a United Nations report cited by Brugmann, it is expected that globally climate change is going to cost between $49 and $171 billion by 2030. Most of these costs will be for urban environments. The suggestions for financing the development of resilience standards and their implementation in these environments have ranged from private investments to tax-supported development. In all likelihood, a combination of these methods will be the most expedient approach.

The expectation that these urban environments will be able to fund these resilience efforts on their own is unrealistic and countries with intergovernmental finance will need to see more intergovernmental aid to support the more vulnerable areas of the country. Even within these cities, the most vulnerable areas are typically those areas with the most poor. As described by Vale and Brugmann, resilience in cities is only as effective as its weakest area and resilience should strive to be equitable and fair. Equality in this case means that those most affected by these disasters receive more assistance.

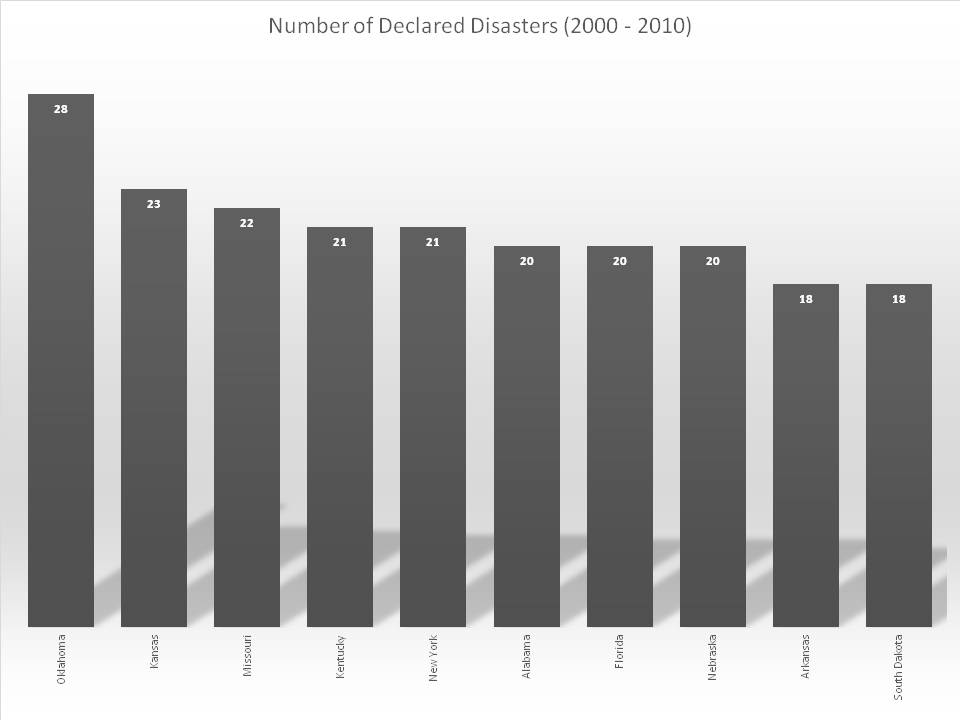

Data on the number of declared disasters by state between 2000 and 2010 indicate that cities in the states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Kentucky and New York are at most immediate risk to disasters that threaten the resilience of these cities. The table below shows the top 10 states between 2000 and 2010 in regard to declaring disasters. These instances are recorded by the Federal Emergency Management Administration. The assumption would be that the cities in these states would be at the forefront of the resiliency effort in the United States.

The 100 Resilient Cities Foundation, which is part of the Rockefeller Foundation, has been at the forefront of encouraging cities around to world to be more resilient, which they define as surviving, adapting and growing. In December 2015, the Foundation ascertained pledges from 22 cities around the world to dedicate 10 percent of their budgets without raising additional taxation or other sources of funding toward resilience-building in their cities. Seven of those cities are in the U.S. and include Boulder, Norfolk, Tulsa, Oakland, Berkeley, New Orleans and Pittsburgh. Only Tulsa has made this commitment among cities in disaster-prone states. Pittsburgh and New Orleans are declining cities with a sizable vulnerable population to flooding and storms, so their pledge is understandable given their context.

The pledge these cities have made is a commitment to build resilience to both systemic inefficiencies and potential catastrophes. The areas of focus regard energy, infrastructure, participatory budgeting, revitalization and transportation. These areas have been identified by the Foundation as important elements in resilience efforts.

It is unknown if the dedication of 10 percent of these cities’ budgets to these efforts is adequate to cover the real costs. It can only be assumed it is not and these cities will still require substantial private investments and intergovernmental aid. Either way, the symbolic acceptance of needing to be more resilient by earmarking a sizable portion of the budget to resiliency is an important step.

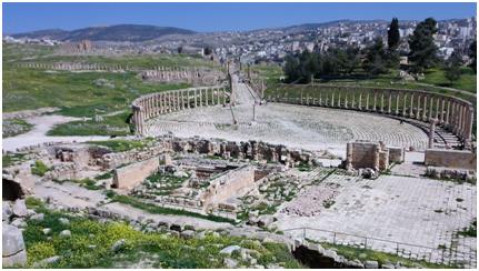

The growing importance of these planning efforts in cities around the world are designed to ensure they do not become another Jerash, an ancient Roman city in present-day Jordan destroyed in the eighth century by an earthquake, or the multitude of cities around the world that failed due to catastrophes or systemic failures. These cities serve as examples of what present-day cities could look like without adequate preparation.

Photo credit: Daniel Hummel

Author: Daniel Hummel Ph.D. is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Idaho State University.

(7 votes, average: 4.71 out of 5)

(7 votes, average: 4.71 out of 5)

Follow Us!