Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Public Service and the First Amendment

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Thomas E. Poulin

January 31, 2020

Over the past few years, we have experienced increasing unrest in many communities. It often begins as a form of political debate—a form of civic engagement in which everyone, including public employees, might wish to participate. This debate might include protest behaviors which by themselves are neither illegal or unethical. The challenge for public sector leaders is to identity and hold the line between acceptable and unacceptable employee behaviors.

The United States emerged from protests by colonists against the British Crown. When the protests began, most colonists considered themselves loyal British subjects, with concerns focused on legislative acts of Parliament rather than at King George. At first, these protests took the form of sending representatives or letters to Great Britain, hoping for some form of redress. When their voices went unheard, when matters worsened, the protests evolved into revolution. The rest is history. The context between 1776 and today is vastly different, but those events had a lasting influence on our political discourse.

The First Amendment to the Constitution states: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” The right of protest is not mentioned specifically in the Constitution, but it is integral to the freedoms of (1) speech), (2) press, (3) peaceable assembly, and (4) petitioning for redress of grievances. As public servants, we are expected to both respect and protect Constitutional liberties.

The First Amendment prohibits government from impinging on freedoms. This creates an area of ambiguity when the government is the employer. Public employees do not shed their rights as citizens when they enter public employment. However, they may face reasonable limitations on behaviors in the workplace, or those which appear to represent the workplace, which might otherwise appear to be covered by the First Amendment. The courts have been consistent in this, noting a balance must be struck between the rights of individuals and the employer-employee relationship, even when the government is the employer, if good order within an agency is to be maintained.

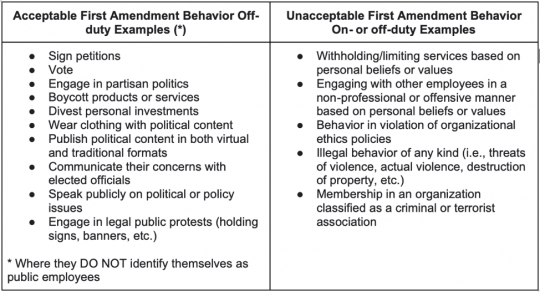

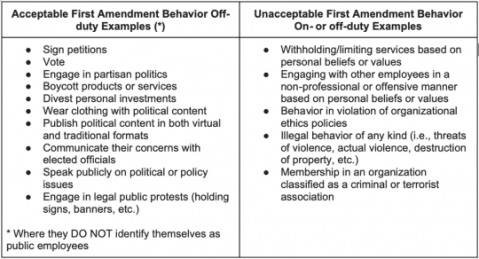

Public agencies should have policies which recognize the rights of employees to engage in political debate within the community, providing guidelines on what might be considered acceptable behaviors. When off-duty, outside the workplace, when not representing themselves as public employees, they are free to sign petitions, to vote, to engage in political debate, to participate in peaceful protest and any other such activities associated with citizenship in a democratic republic. These types of behaviors are clearly acceptable for any public sector employee, and public sector leadership must ensure they do stifle such behavior, even if only unintentionally.

Author: Thomas E. Poulin, PhD, MS(HRM), MS(I/O Psych.) is an Independent Scholar and HR Consultant. He served in local government for over thirty years and as full-time faculty in public administration-related programs for more than ten. He is the President of the Hampton Roads Chapter of the American Society for Public Administration. He may be reached at [email protected]

Mark A. Fulks, J.D., Ph.D.

February 1, 2021 at 2:49 pm

Non-lawyers should not give legal advice, even in columns such as this one. This article does not accurately relay the First Amendment issue in public employment, starting with the fact there the right to protest is encompassed within the right to peaceably assemble. Moreover, public employees have a First Amendment right to comment on matters of public interest only as long as their public comments do not discuss issues of public concern as long as their public comments do not undermine the efficiency of the public office. All of the issue identified in this article as “Acceptable” could result in termination if the public comment negatively impacts the operations of public office. This is especially so give the prevalence of “cancel culture” in our society. Any one of those behaviors could result in a public backlash against the office that hampers its effectiveness and efficiency.

Dr. Michael A. Brown

January 31, 2021 at 7:49 pm

Tom, nice,but how has this influenced/impacted race relations? If any of this were to be about persons of color would your perspective be different? Foe example,”The prohibitions against illegal behavior or non-professional conduct likely fit within general expectations for employee behavior, though it would do no harm to emphasize them in policies on political engagement (Poulin, 2021).” But the mere fact a person is affiliated with BLM or “legitimate” peaceful protest might be viewed by Eurocentrics or Dominant Anglo males is not even an issue for cerebral or ethical debate.