Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Public Service Values and Motivation in the MPA Classroom: An Exercise

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Daniel Hummel

November 2, 2018

Recently, in one of my MPA classes, I covered the topic of public service motivation. In preparation for the class, the students read the article “Public Service Motivation Research: Lessons for Practice” by Christensen, Paarlberg and Perry. I had them focus on the five lessons in the article, as a few things were of interest to me in the article and I wanted to highlight them in the class. One lesson was on the need for creating a supportive work environment through organization socialization. The authors highlighted the need for socialization more than once in the article. Based on their assessment of the research, it is incumbent upon a public service organization or any organization for that matter to project a proper image of itself to attract those who will best match the values of the organization. This is only part of the struggle as the organization needs to invest time and resources in these new hires to cultivate organizational values and expectations within them. The assumption is that there are general values in society and within the particular field, in this case public service, and there are specific values in each organization that need to be internalized by those in it.

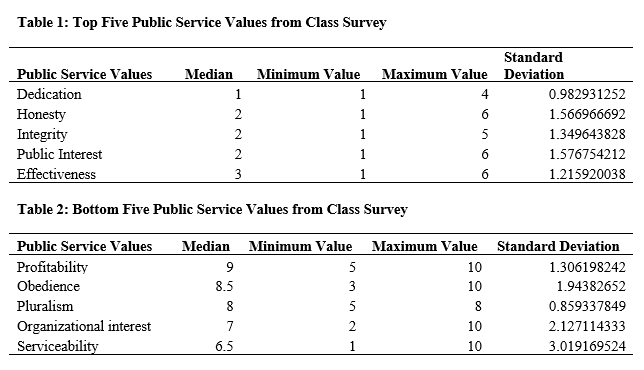

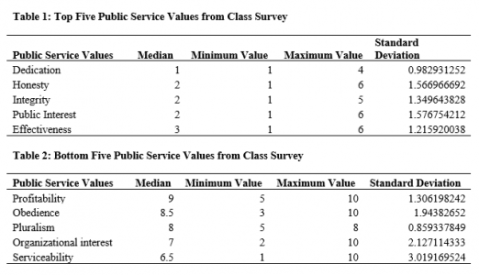

On the topic of public service values, I had the students do a survey where they ranked some of these values that were highlighted in the article “Integrating Values Into Public Service: The Values Statement as Centerpiece” by Kernaghan. I aggregated the results and shared them with the class. The value that received the highest ranking was “dedication,” followed by “honesty,” “integrity,” “public interest” and “effectiveness.” There was less deviance around the ranking of “dedication” indicating that there was a greater class consensus around this value among the top five values. The value ranked the lowest was “profitability” preceded by “obedience,” “pluralism,” “organizational interest” and “serviceability.” There was less deviance around “pluralism” in the ranking indicating greater consensus on its rank.

In table 1, four of the five values could be extrapolated to any organizational context. It would be hard to imagine an organization wishing to hire someone who did not equally value being dedicated, honest, effective and having integrity. Uniquely to students in public administration is the emphasis on the “public interest.” Also, uniquely to these students is the lack of emphasis on “profitability” in table 2. What is interesting about these results is those values that are considered professional values based on the categorization of Molina in his article “The Virtues of Administration: Values and the Practice of Public Service” have been ranked the lowest. Using the same categorization those values ranked the highest are equally split between ethical and professional values. Only one democratic value was represented in the top five (public interest) while another democratic value was represented in the bottom five (pluralism). Other democratic values like “social justice,” “transparency” and “inclusiveness” ranked in the middle.

In the class we discussed how these values are important in aligning with public service organizations and their work. Connections were made with the lessons in the article. For example, one

Classroom at Bowie State University (photo belongs to the author)

lesson encouraged the development of a clear connection between the beneficiaries of the public programs and those implementing them i.e. the public servants. This encourages the “public interest” value that many of those pursuing work in public administration should have in ample quantities. I also asked the class in the same survey if they felt that incoming job candidates should be screened for public service motivation such as valuing the public interest and nearly 90 percent agreed with this. The loss of a connection in the day-to-day work of public servants with the actual public decreases public service motivation and squanders the drive many have when they pursue these careers.

Finally, we discussed the last lesson in the article on “transformational leadership.” The article noted these leaders are tasked with fostering public service motivation by navigating the conflicting public service values and building value consensus. The authors argued that the best leaders appeal to those who have high levels of public service motivation which they encourage through employee empowerment. This was also a factor in creating a supportive work environment which they express as facilitating a sense of competency and autonomy as basic psychological needs. Another question on the survey asked how important they felt transformational leaders are for fostering public service motivation. More than 90 percent of the class felt that they are either very important or extremely important.

Through this class exercise we were able to explore public service motivation and the relevance of public service values. This involved a survey to the class on these values in addition to exploring different topics covered in the article which facilitated a deeper discussion on human resources management, leadership and organizational design with public service organizations. It also allowed the students to explore their own desires to pursue or continue careers in public service and renewed vigor for this work.

Author: Dr. Hummel is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science in the Public Administration Program at the University of Michigan, Flint. He teaches classes on public policy, intergovernmental relations and public administration. His office # is 810-237-6560. His email is [email protected].

(5 votes, average: 4.80 out of 5)

(5 votes, average: 4.80 out of 5)

Follow Us!