Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

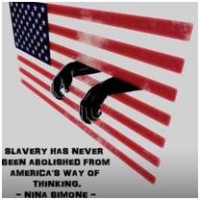

Race and Law Enforcement: A Tale of Two Experiences

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Brandi Blessett

April 14, 2015

In December 2014, my colleague Tia Sherèe Gaynor and I wrote an article in PA Times titled “Ensuring that #BlackLivesMatter.” That article made connections to the historic legacy of violence perpetrated by law enforcement officers against black and brown communities. It emphasized the need for cultural competence training to help combat deeply rooted prejudices, ideologies and negative social constructs that inform and in some cases justify such brutality.

Not to our surprise, we received comments both publicly and anonymously that not only questioned our credentials, but argued that we were biased in our interpretation of the problems. In many respects, such comments are representative of the broader society, which often minimizes any criticism of law enforcement officers as racially motivated or better yet unpatriotic.

Below is a list with the names of men, women and children who have been killed by police officers from August 2014 through December 2014.

| Ezell Ford | David Hooks | Akai Gurley |

| Dante’ Parker | Dillion McGee* | Carey Smith-Viramontes |

| Michelle Cusseaux | Miguel Benton | Tamir Rice |

| Diana Showman* | VonnDerrit Myers | Rumain Brisbon |

| Kajieme Powell | Elisha Glass | Delbert Rodriguez |

| Maria Godinez | Quesean Witten | Travis Faison |

| Roshad McIntosh | Jack Jacquez | Brandon Tate-Brown |

| Desean Pittman | Laquan McDonald | Allen Locke |

| Karen Cifuentes | Jeffrey Holden | Dennis Girigsby |

| Darrien Hunt | Kaldrick Donald | James Long |

| Sergio Ramos | Cinque D’Jahspora | Antonio Martin |

| Levi Weaver | Aura Rosser | John Crawford |

| Cameron Tillman | Tanisha Anderson | |

| * White victims |

More recently, on March 25, 2015, a patrol car video was released showing officers beating Floyd Dent, a Detroit man and longtime autoworker with no criminal history. According to the report, one of the officers involved in the incident, had been previously accused of misconduct. Fortunately, Dent survived his brutal encounter. However, far too often interactions between police and people of color result in injury or death.Whether the larger society acknowledges the racially disparate treatment of nonwhite people by law enforcement to be a problem or not, a growing faction of communities of color experience the oppressive regimes of local law enforcement on a daily basis.

To illustrate this point, Martese Johnson, an honor student at the University of Virginia, was “beaten like a dog” on March 18, 2015, by Virginia’s Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control officers for allegedly trying to enter a bar with false identification. Reports later revealed that Mr. Johnson had proper identification and was not intoxicated.

Killed by Police is reporting that as of April 3, 2015, nonmilitary law enforcement officers have killed 298 people. Despite cries of frustration about the pervasiveness of brutality in its many variations (e.g., searches, seizures and surveillance) and appeals for justice, this issue seems to fall on deaf ears. It appears as if the experiences of persons of color do not live up to the normative and idealized assumptions held about the “integrity” of law enforcement officials.

Time and again, society finds it easier to blame the victim (e.g., if she had just cooperated, if he did not look so suspicious), instead of examining the institutional structures, public policies (e.g., stop and frisk) and organizational and individual biases that are rooted within the criminal justice system.

One only needs to examine the recent tragedy in Mesa, Arizona where Ryan Giroux, a white perpetrator, killed a man and wounded five others in a series of shootings on March 18,2015. Even after going on a rampage which resulted in a hours-long manhunt, Giroux was not labeled a terrorist and was approached with the least amount of aggression ( a Taser was used) to take him into custody. This exemplifies white privilege.

The recently published report by the Department of Justice on the Ferguson Police Department (FPD) sited that the FPD engaged in patterns of unconstitutional traffic stops, arrests and excessive force that violated the Fourth Amendment and engaged in a pattern of First Amendment violations. Furthermore, the municipal court practices also came into question, particularly regarding the imposition of substantial and undue barriers to challenge fines and violations. In this case specifically, the justice system and its many component parts have been complicit in perpetuating institutionalized racism and discrimination, which has fueled feelings of distrust, apathy and disgust on behalf of black Ferguson residents.

For a great number of people of color, this IS reality and their subsequent outrage and anger is most certainly justified. The question becomes what do we do about it?

First, society must recognize that institutional racism is a central manifestation of disparate treatment of people of color within the criminal justice system. Its legacy is pervasive and continues to inform the behaviors of police officers who interact with people of color. This first step is a monumental acknowledgement because it then forces the examination of policies, practices and organizational culture that substantiates conscious and unconscious bias. Without this first step, any attempt toward building healthy communities becomes as much of a myth as ‘justice is blind.’

Author: Brandi Blessett is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Policy and Administration at Rutgers University-Camden. Her research broadly focuses on issues of social justice. Her areas of study include: cultural competency, social equity, administrative responsibility and disenfranchisement. She can be reached at [email protected].

(12 votes, average: 3.75 out of 5)

(12 votes, average: 3.75 out of 5)

Pingback: The Cost of Police Misconduct | PA TIMES Online