Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Reforming New York State’s Budget Process – Proposals for a More Effective State Budget

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Stephen R. Rolandi

May 20, 2024

“Excelsior” (translation: “Ever Upward”) – Official motto of the State of New York

“Waste neither time nor money, but make the best use of both.” – Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

Early in my career, a former boss of mine who had served as Vice President and Treasurer (CFO) for a leading not-for-profit, international education student exchange organization based in New York, would tell his staff that a budget was the “lifeblood of an organization.” Looked at another way, budgets, particularly governmental budgets, represent statements made by elected officials about values and policies for its citizens.

The budget process (“budget making”) is the arena where governments (Federal, state and local) determine public priorities by allocating financial resources among competing claims. Critical to the budget process is the ability for the legislative branch of government to adopt budgets at or before statutory deadlines.

Analysts and observers of the budget process will tell you that passing “on-time” budgets is imperative in implementing programs and activities directed by law and in the best interest of the American people.

Unfortunately, this is becoming less the case for on-time budgets. For example, in the case of Federal budgets, in 45 of the past 48 years, the Federal government has operated under continuing budget resolutions (CRs) which basically extend the prior year’s funding and priorities into the following (new) fiscal year to avoid a lapse in appropriations and a government shutdown until regular annual spending is enacted (note: there have been government shutdowns in recent years).

At the state level, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, ten states in a recent study failed to pass a budget by the beginning of their fiscal year (July 1 in most states). The all-time record is held by the State of Illinois, which in 2017 (according to the NCSL study) went a whopping 736 days without passing a two-year (biennial) budget. Not surprisingly, Illinois’ credit rating was one of the lowest in the nation until recently, according to the major credit rating agencies (Standard & Poor’s; Moody’s and Fitch).

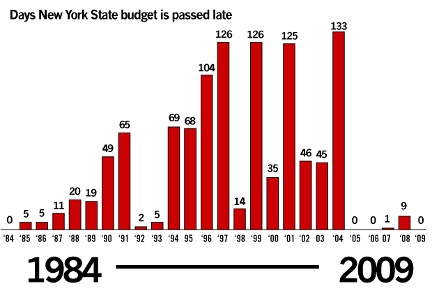

This month’s article focuses on the problem of on-time budgets in my home state and former employer. The chart below tracks the number of days the New York State budget was passed late or on time, from the administration of Governor Mario M. Cuomo through Governor David Paterson’s penultimate budget.

This pattern has continued through the administrations of Governors Andrew M. Cuomo and his successor, Kathy C. Hochul—it should be noted that Governor Andrew Cuomo had four on-time enacted budgets during his first term in office. New York State’s budget for Fiscal Year 2024-25 is $237 billion—second only to California’s of $ 291.5 billion) was passed 20 days late last month.

There are various reasons for many New York State budgets being enacted late (past the April 1st fiscal year start date):

- Existing budget monitors, such as the independently elected State Comptroller and Authorities Budget Office, have seen their power and authority reduced over time, which precludes comprehensive oversight of the state budget; New York State also lacks an independent budget office to provide nonpartisan, independent oversight and analysis of budgetary and fiscal decisions;

- Existing law, rules and common budgeting and reporting practices limit the state’s ability to make sound fiscal decisions. New York, as many observers have noted, places too much reliance on the cash basis of accounting and budgeting methodology that obfuscates actual spending trends and budget balance;

- Budgetary and fiscal management decisions are not informed by a comprehensive public performance measurement and management system – this not only hampers quality operational management, but it also leads to a lack of information to make evidence-based decisions during budget deliberations and implementation;

- New York’s budgeting is also opaque and limits public and legislative review of fiscal decisions as they are being made. Some budget appropriation bills and other legislation are not accompanied by fiscal impact estimates. Further budget bills are also voted on quickly, reducing the opportunity for meaningful review by the Legislature and the public.

There are a number of proposals advanced by good government groups and others to reform and strengthen New York State’s budgetary process:

- New York’s fiscal year should be moved to July 1st (currently April 1st), which is what nearly all of the other states have. The July 1st date would coincide with the end of the state legislative session, which would give legislators an added incentive to adopt the state budget on time. As was noted by the late Richard Ravitch, Lt Governor during the Paterson Administration, moving to a July 1st fiscal year would make revenue forecasts more accurate, as the state would then have data from the April 15 tax filings to have more robust revenue estimates;

- Establish an independent fiscal analyst’s office/independent review board as exists in: California, Washington and Pennsylvania;

- Restore the Controller’s oversight of procurement and contracting;

- Fully fund the State Authorities Budget Office;

- Require financial plans and estimates with all budget bills and other proposed legislation;

- Implement comprehensive, transparent long-term capital planning processes.

These reforms would go a long way towards making New York’s budget processes more transparent and timely. They will require leadership and citizen action to make them a reality. As in most things in this life, time will tell.

Postscript

For further reading, I suggest consulting the following publications and reports:

- Empire Center for Public Policy Reports (www.empirecenter.org)

- National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) Reports and Publications (www.nasbo.org)

- Dall W. Forsythe and Donald J. Boyd, “Memos to the Governor: An Introduction to State Budgeting,” 3rd Edition (2012)

- State and Local Finance Initiative of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (www.taxpolicycenter.org)

Author: Stephen R. Rolandi retired in 2015 after serving with the State and City of New York. He holds BA and MPA degrees from New York University, and studied law at Brooklyn Law School. He teaches public finance and management as an Adjunct Professor of Public Administration at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (CUNY) and Pace University. Professor Rolandi is a Trustee of NECoPA; President-emeritus/Senior Advisor for ASPA’s New York Metropolitan Chapter and past Senior National Council Representative. He has served on many association boards, and is a frequent guest commentator on public affairs and political issues affecting the nation and New York State. You can reach him at: [email protected] or [email protected] or 914.441.3399 or 212.237.8000.

Follow Us!