Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

Repeal and Replace and the Role of Public Administration

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Cheryl A. Camillo

July 11, 2017

Congress is currently considering enacting a full or partial repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). While much has been said about the policy implications of repeal legislation—for example, its effects on insurance premiums and coverage—the implications for public administration have largely been ignored. Yet, they would be massive. Implementation of any reforms would require tremendous effort on the part of federal, state and local agencies. Failures to implement them well and on time would result in confusion, loss of trust and further damage to the morale of public employees. Even successful implementation could negatively impact the public workforce.

This column, the first in a serious about health reform and public administration, calls on scholars and practitioners to insert public administrative perspectives into the debate. It also offers a suggestion as to how to promote their inclusion.

The U.S. health care system is so complicated that even relatively minor reforms require significant time and effort to implement. For example, the proposed provision to roll back the minimum Medicaid income standard for children ages 6 to 19 from 133 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) to 100 percent would require each state at minimum:

- Issue regulation and sub-regulatory guidance

- Edit eligibility information and related technology systems

- Train hundreds, if not thousands, of caseworkers

- Revise program materials and disseminate information to the public

In fact, prior to the ACA, such a change in eligibility would have been considered a significant reform. Currently, both the House of Representatives’ American Health Care Act and the Senate draft discussion bill would make multiple provisions such as this effective as of October 1, 2017. Even if a repeal and replace bill passes both chambers and is enacted later this month, it is unlikely states could implement these provisions on time. Most state legislatures have adjourned for the year, which makes it difficult for Medicaid agencies to get the authorizing legislation and funds needed to proceed.

Two of the primary lessons of the ACA were policymakers must allow sufficient time for implementation and should include public administrators in the policymaking process. As many readers are no doubt familiar, the federal and several state Health Insurance Marketplaces collapsed shortly after they went live in October 2013. Debriefs confirmed that there was insufficient time to design and build the technology platforms upon which they were erected once detailed policy guidance was released. My own research revealed that policymaking stalled due to the exclusion of street-level operational perspectives from the process. As recently as December, in responding to the National Association of State Medicaid Directors 5th annual operational survey, two directors reported that completing ACA implementation activities was still a top priority. Several others emphasized needing to complete their system builds.

Implementation problems erode public and institutional support. According to the Kaiser Health Tracking Poll, which has monitored public opinion about the ACA since 2010, fewer Americans felt favorably about the law in November 2013, the month after the Marketplace crashes, than at any other time. As described in a June PATimes column by Max Richtman, the president and CEO of the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare, about the Social Security Administration’s struggles to keep up with growing customer service demands, angry public reactions to implementation failures often lead to the withdrawal of resources from the public administrators deemed responsible for them.

Most employees would find it difficult to perform high profile, controversial, complicated tasks without sufficient support, but public employees sometimes face the additional challenge of having to suddenly undo their work, as would be the case if repeal and replace legislation passes. Reversing work is especially troubling when it is done for political reasons because it violates the ethic to manage taxpayer resources in the best interests of the public.

The recent bibliometric analysis of the Public Administration Review (PAR) articles by Chaoqun Ni, Cassidy R. Sugimoto and Alice Robbin provided further evidence the health policy discipline does not consider public administration. Between 1990 and 2013, just 0.79 percent of articles in health policy and services journals cited PAR articles.

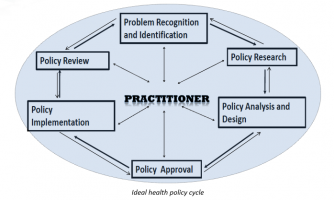

As supporters of public administration, we need to assert its importance to the policy community. One way to do so would be to speak of its practitioners as being at the center of the policy cycle. Public administrators are commonly excluded until the implementation stage, yet they cannot successfully implement policies that will solve health policy problems unless their needs are considered at each stage of the cycle.

Author: Cheryl A. Camillo is an assistant professor at the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. A former public administrator at the U. S Department of Health and Human Services and Maryland Department of Health, she works to bring together scholars and practitioners to solve real-world health policy problems. She can be reached at [email protected] or via Twitter @CherylACamillo.

Follow Us!