Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

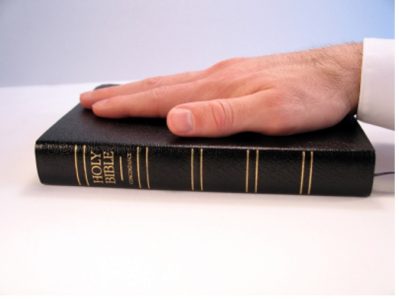

Sacred Obligation

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Anna Marie Schuh

October 11, 2024

“I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; … I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same…” I cannot remember how many times I said these words during my 36 years as an executive branch merit system employee, but I know it was meaningful every time. Still, taking this oath is very routine because every federal employee does it. Why they take the oath and how that oath-taking affects the employees who take it is the subject of this column.

The question of who or what deserves the loyalty of the bureaucracy was at issue early in the history of the country. For example, in 1803 Chief Justice John Marshall cited the oath of office as the power of the courts to declare acts of Congress unconstitutional. President Andrew Jackson noted that everyone takes an oath to the Constitution and added that every individual must act on that oath based on their individual understanding of the Constitution when he vetoed a bank charter despite a Supreme Court ruling in favor of the bank. John Rohr observed the oath public administrators take is a moral oath based on religious belief in a higher authority. Rohr concluded that the Constitution is a covenant rather than a command, meaning that the Constitution is an agreement of how we as a civil society will treat each other in this joint governance effort.

In the context of a covenant, qualifications for federal employment have evolved over time. For example, President George Washington focused on fitness. Washington tried to move away from old European relationships and social connections in appointments. He knew he would be setting standards for the future, and he felt fitness selections would be essential in avoiding government corruption. His definition of fitness centered on character and support of the revolution.

Andrew Jackson, the first president elected after the vote was extended to all white male—even those without property, added partisanship as a selection criterion. He believed in job rotation and a simple government, subsequently replacing about a fifth of the federal workforce with political supporters. This set the stage for the rise of the spoils system with its partisanship underpinnings.

Jackson’s system continued until the passage of the Pendleton Act in 1883. The Pendleton Act merit system replaced the spoils system for several reasons. Lack of effectiveness during the civil war emphasized problems with non-merit selections. The business community pressured for reliable government services without corrupt practices. The assassination of a president by a disgruntled office seeker highlighted the need for a skills-based system in the eyes of the public. Finally, the party in power wanted to retain employees in government after losing the mid-term elections and expecting to lose the upcoming presidential election. Despite the evolution of the federal employment system over time and the motivations of those who changed it, until recently government employment focused on some sense of merit together with allegiance to the Constitution.

Today, that allegiance is threatened. More specifically, Project 25, which has strong support from some political candidates, seeks to refocus bureaucratic loyalty from the Constitution to an individual. While many of the project’s proposed actions were attempted during the previous administration, the actions were not broad policy. Project 25 now centers on making the following recommendations the new normal:

- Substitute partisan loyalists for non-partisan loyalists. The Schedule F executive order during the last administration was an attempt to do this. Currently, that executive order has been rescinded.

- Relocate federal agencies to force career experts out of government. The Department of Agriculture Research Service was damaged by this approach during the previous administration.

- Alter security clearance provisions. This was done on a smaller scale during the previous administration with the president personally providing clearances to many who were denied clearances through the regular screening process.

- Require ideologically based screens in the Federal hiring process. Allies of a current candidate are already prescreening supporters to have up to 54,000 pre-vetted individuals with loyalty to the candidate and ready to carry out the candidate’s policies.

Effective public administrators anticipate future challenges and develop strategies for dealing with such initiatives. The above actions are definite possibilities; however, none of these actions eliminate the oath public administrators take to uphold the Constitution. So public administrators need to think about their oath, its history and its effect on potential post-election policies.

George Washington, in his farewell address to the country noted: “…the Constitution …is sacredly obligatory upon all. The very idea of the power and the right of the people to establish government presupposes the duty of every individual to obey the established government.” This is the covenant that Rohr refers to and it is the rationale for why all federal officials, merit or politically appointed, must adhere to the Constitution and not to the will of a group or an individual.

Author: Anna Marie Schuh is currently an Associate Professor and the MPA Program Director at Roosevelt University in Chicago where she teaches political science and public administration. She retired from the federal government after 36 years. Her last federal assignment involved management of the Office of Personnel Management national oversight program. Email: [email protected]; X: profschuh.

skip

October 11, 2024 at 4:05 pm

Excellent article! Much like Franklin’s quip, “…here’s a Republic. If you can keep it!” You extol a reminder about the foundations of public service (along with its perils) if we lose sight of the covenants that ARE the underpinnings of public service! ~skip