Should Policy Research Increase the Use of Experimental Research?

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Bill Brantley

June 11, 2018

The successful emergence of behavioral economics can be traced to using experiments in testing fundamental economic assumptions and concepts. The most famous example of how experimenters created behavioral economics is through the ultimatum game. The rules of the ultimatum game are simple. One participant is given an amount of money to split with a second experiment participant. According to the neoclassical economic theory of the rational economic person, the second participant should accept even the most one-sided splitting of the money.

However, in numerous iterations of the ultimatum game among different cultures, researchers found that the different cultures had a fairness level. Many participants would refuse the split if they felt that the split was unfair. The findings of this experiment and similar economic games demonstrated that the original economic principle of the rational person to be expanded. A new field of economics was born out of experimentation.

The History of Experimentation in Policy Research

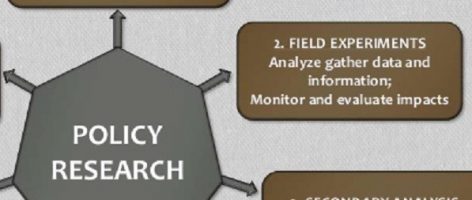

Huitema, Jordan, Munaretto and Hilden (2018) write in a recent editorial note in about the use of experimentation in policy research. As the authors explain, policy research has a long history of using experimentation as a research method. Experimentation was a key concept of pragmatism and championed by both Charles Peirce and John Dewey. Peirce advocated experimentation as a method of scientific research while Dewey saw experimentation as an approach to governance. These two perspectives evolved into two variants. The first is “Darwinian experimentalism” in which many approaches are tried. The second variant is “generative experimentalism,” focuses on one specific innovation and iteratively improves on the innovation through a series of experiments.

Huitema, Jordan, Munaretto and Hilden (2018) write in a recent editorial note in about the use of experimentation in policy research. As the authors explain, policy research has a long history of using experimentation as a research method. Experimentation was a key concept of pragmatism and championed by both Charles Peirce and John Dewey. Peirce advocated experimentation as a method of scientific research while Dewey saw experimentation as an approach to governance. These two perspectives evolved into two variants. The first is “Darwinian experimentalism” in which many approaches are tried. The second variant is “generative experimentalism,” focuses on one specific innovation and iteratively improves on the innovation through a series of experiments.

Then, there is the influence of Donald T. Campbell. He promoted experimentation, especially randomized experiments, as the defining standard for research. Campbell created the concept of the “experimenting society” with these characteristics (from Huitema et al.’s editorial note):

- “A preference for decentralization and diversity.”

- “An inclination towards action rather than inaction.”

- “A premium on honest assessment based on transparent data produced in an accountable manner.”

- “Willingness to change theories and values in the face of disconfirming evidence.”

Despite this history, experimental studies are rare in the policy research field and mostly confined to social policy and education. When experimentation is used in policy research, it is often the Peirce view of experimentation as classical science research. Critics of experimentation argue that experiments can stifle intellectual progress because experiments focus “exclusively on means and not goals” and experiments “use significant time and resources” while focusing on “one idea at a time.”

The Four Questions of Modern Policy Experiments

Huitema et al. describe four questions concerning experimentation in research:

- Experiments shape the reality of the system being studied by the effect that the intervention has on the system. There is “scientific reality making” which affects what is learned from the experiment and there is “political reality making” which affects the political environment around the experimental intervention.

- Policy experiments are inherently political in that the “starting premises of an experiment are often highly consequential.” The choice of an experimental intervention determines which political viewpoint and political actors will prevail in the specific policy area under study.

- How the policy experiment is governed is also influenced by the choices such as the “type of information that is regarded or ignored, the authority to make decisions on the experiment, the costs, and benefits associated with the experiment.” Governance decisions also play in the reality-making function and political impacts of the policy experiment.

- The final question concerns how the lessons learned from the experiment are received by policymakers and other stakeholders. Policymakers are more likely to accept experimental results that are salient, credible, and legitimate. In the long term, “experiments are likely to play a role in the gradual sedimentation of ideas in policymaking.” However, the acceptance of the experimental results increases when the results align with pre-existing policy goals.

The Potential and Challenges of Policy Experiments

Policy experiments have great potential as evidenced by the groundbreaking results of experiments in other social science fields. Also, experimentation has a long tradition in policy research. What stands in the way, according to Huitema et al., is “conceptual precision”— an explicit definition of a policy experiment. Researchers also must know of the “political dynamics surrounding and within experiments” and the governance of policy experiments. Finally, it remains “unclear which factors determine whether certain experiments lead to learning and policy change.” The authors argue that policy experiments should be more than just a research method but may have a greater impact as a “broader approach to governing.”

Author: Bill Brantley teaches at the University of Maryland (College Park) and the University of Louisville. He also works as a Federal employee for the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. All opinions are his own and do not reflect the opinions of his employers. You can reach him at http://billbrantley.com.

(2 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

(2 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

Loading...

Loading...

Should Policy Research Increase the Use of Experimental Research?

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Bill Brantley

June 11, 2018

The successful emergence of behavioral economics can be traced to using experiments in testing fundamental economic assumptions and concepts. The most famous example of how experimenters created behavioral economics is through the ultimatum game. The rules of the ultimatum game are simple. One participant is given an amount of money to split with a second experiment participant. According to the neoclassical economic theory of the rational economic person, the second participant should accept even the most one-sided splitting of the money.

However, in numerous iterations of the ultimatum game among different cultures, researchers found that the different cultures had a fairness level. Many participants would refuse the split if they felt that the split was unfair. The findings of this experiment and similar economic games demonstrated that the original economic principle of the rational person to be expanded. A new field of economics was born out of experimentation.

The History of Experimentation in Policy Research

Then, there is the influence of Donald T. Campbell. He promoted experimentation, especially randomized experiments, as the defining standard for research. Campbell created the concept of the “experimenting society” with these characteristics (from Huitema et al.’s editorial note):

Despite this history, experimental studies are rare in the policy research field and mostly confined to social policy and education. When experimentation is used in policy research, it is often the Peirce view of experimentation as classical science research. Critics of experimentation argue that experiments can stifle intellectual progress because experiments focus “exclusively on means and not goals” and experiments “use significant time and resources” while focusing on “one idea at a time.”

The Four Questions of Modern Policy Experiments

Huitema et al. describe four questions concerning experimentation in research:

The Potential and Challenges of Policy Experiments

Policy experiments have great potential as evidenced by the groundbreaking results of experiments in other social science fields. Also, experimentation has a long tradition in policy research. What stands in the way, according to Huitema et al., is “conceptual precision”— an explicit definition of a policy experiment. Researchers also must know of the “political dynamics surrounding and within experiments” and the governance of policy experiments. Finally, it remains “unclear which factors determine whether certain experiments lead to learning and policy change.” The authors argue that policy experiments should be more than just a research method but may have a greater impact as a “broader approach to governing.”

Author: Bill Brantley teaches at the University of Maryland (College Park) and the University of Louisville. He also works as a Federal employee for the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. All opinions are his own and do not reflect the opinions of his employers. You can reach him at http://billbrantley.com.

Follow Us!