Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

The Black American Middle Class

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By David Hamilton

April 3, 2021

Several years ago friends indicated that they were relocating to an, “Upscale, Black, middle class neighborhood.” For us, the description was bewildering. Why would race, class and lifestyle be requisite to describing their new home? The reason, this is America!

Starting in the 1950s, the booming economy of the post war era brought remarkable prosperity to millions of Americans. High-paying industrial jobs were plentiful. The GI Bill opened advanced educational opportunities and a plethora of suburban housing with new schools spawning communities for the expanding middle class to call their home. But through implicit and explicit exclusionary policies, these places were not for all.

In The Color of Law, Richard Rothstein reminds us that, “Until the last quarter of the twentieth century, racially explicit policies of federal, state and local governments defined where Whites and African Americans should live.” When successfully challenged in court as violations of the Constitution and Bill of Rights, “Real estate agents steered Whites away from Black neighborhoods, and Blacks away from White ones while banks discriminated with ‘redlining,’ refusing to give mortgages to non-Whites or extracting unusually severe terms from them with subprime loans.”

It was not surprising then, that newly prosperous Black families would locate to communities where they were welcomed, creating racial concentrations of the middle class. But these groupings were relatively small compared to White middle-class communities. In describing the rise of suburbia in his classic Edge Cities, Joel Garreau noted that, “in 1950, less than 1% of all Black people had a median income equal to that of White people with white-collar jobs when an income of $5,000 a year was upper middle class for Whites. Perhaps seventy-five thousand Black people in the whole country made that kind of money, out of a total Black population of fifteen million.”

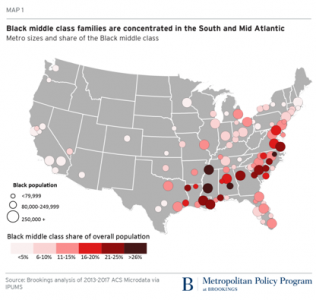

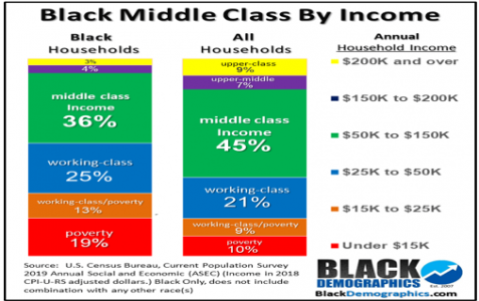

As BlackDemographics.com explains, “Things began to change with the Civil Rights movement. Since the 60’s the Black middle class has grown tremendously and African Americans have moved into more white- collar jobs and are more educated than ever before. No longer isolated and identified by skin tone many integrated into White middle class neighborhoods or in some areas developed their own Black middle class neighborhoods.” This improving narrative is demonstrated by the chart below.

Source: BlackDemographic.com

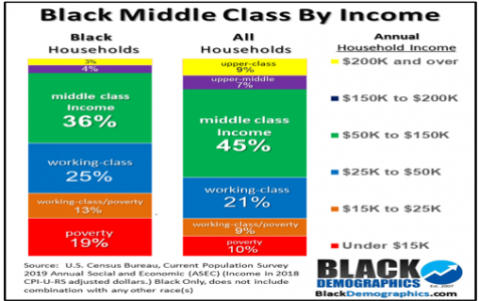

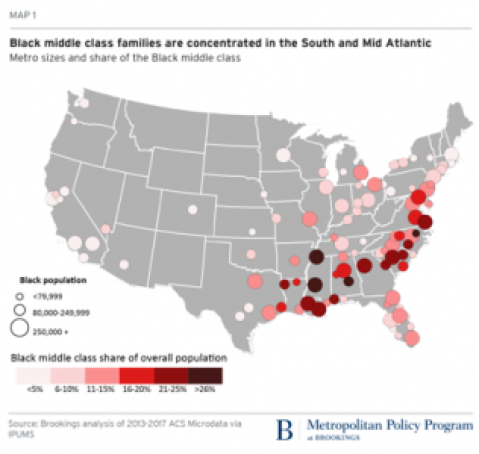

But this only conveys part of the story. Although gaps have narrowed, geographic segregation continues on a national level. In a recent study by the Brookings Institute, large concentrations of Black middle-class families were found in only a few states throughout the southeast. The rest were thinly dispersed within other regions, but are hardly examples of broad integration of living arrangements throughout the country.

Source: Brookings.edu

In addition, the same study notes that economic segregation continues between the general populations of Blacks and Whites, Blacks and Blacks and other minorities. “The median wealth for a White family was $171,000 in 2016, according to the Federal Reserve’s most recent numbers. That number was $17,600 and $20,700 for Black and Latino or Hispanic families, respectively. This huge gulf in wealth warrants a distinct policy agenda for Black families who, even if they have the same income as their White peers, don’t have the same financial cushion.”

So what are we to make of this, and how do public administrators address important issues as we work to re-establish the American middle-class? Start by determining that creating separations predicated on race must end. Where people choose to live and work should be based on opportunities of choice, open to all, as enshrined in the Constitution and Bill of Rights. The reason, as Rothstein states, is compelling by the power of its simplicity. “African Americans of course, suffer from our evasion. But so too, does the nation as a whole, as do Whites in particular. Many of our serious national problems either originate with residential segregation or have become intractable because of it. We have greater political and social conflict because we must add unfamiliarity with fellow citizens of different racial backgrounds to the challenges we confront in resolving legitimate disagreements about public issues.”

But saying it and actually creating and implementing policies to accomplish this elusive goal are fraught with consequences and conflicts for those that attempt to implement change as Rothstein describes.

In 1970, stung by riots in more than a hundred cities by angry and embittered African Americans, HUD secretary George Romney tried to pursue integration more vigorously than any other administration, either before or since. Observing that the federal government had imposed a suburban ‘White noose’ around urban African American neighborhoods, Romney devised a program he called Open Communities. It would deny federal funds ( for water and sewer upgrades, green space, sidewalk improvements, and other projects for which HUD financial support is needed) to suburbs that hadn’t revised their exclusionary zoning laws to permit construction of subsidized apartments for lower-income African American families. The anger about Open Communities among voters in the Republican Party’s suburban base was so fierce that President Nixon reined in Romney, required him to repudiate his plan, and eventually forced him from office.

Author: David Hamilton is a change leader that heads a consulting firm guiding local governments with visioning, planning and organizational alignment. As a public administrator, he led county and city governments to adapt and change. His doctoral studies at Hamline University were based on the impacts of rapid growth and development on Edge Counties. He holds a master’s degree from the University of Minnesota and a baccalaureate from Lakehead University. Hamilton is a member of the Suncoast Chapter of ASPA where he served as Treasure and President. Email: [email protected].

Laurent

November 2, 2021 at 11:57 am

The sentiments on African Americans “suffering” from the evasion of the white American collective not only undermines the potential of autonomy (which African Americans have already demonstrated with the creation of Tulsa, Oklahoma) but it also suggests that further interference by the white collective will somehow solve the current systemic issues that ultimately recreated segregation while simultaneously disfranchising the Black American collective. Fun fact: Although I could live in “white” areas, I choose to live in black “impoverished” areas because white Americans hate admitting to feeling racially superior upfront, but those microaggressions are truly blatant! It is like a climax: we know when you are faking it.