Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

The Equity Challenge

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Parisa Vinzant

September 22, 2019

Equity is hardly a new idea. The issue is as old as democracy itself and can be traced to the writings of Plato and Aristotle. Even Adam Smith, considered the, “Father of Capitalism,” warned of the dangers of economic inequality that could threaten the wealth of a nation and produce, “Corruption of our moral sentiments.” The private sector has embraced the related ideals of diversity and inclusion as essential to a company’s ability to innovate, grow and prosper. In government, social equity has been an important topic in public administration for a half century and in 2005 was named the fourth pillar of the profession by the National Academy of Public Administration.

So why is social equity still largely an aspirational goal rather than operational practice?

Despite the fundamental importance of social equity for a healthy democratic society, efforts by local, state and federal entities to advance it in any meaningful way have been uneven and halting. The persistence of structural racism makes it a formidable problem, but it must be addressed in a focused, long-term way if our country is to avoid sliding into irreparable division, disfunction and decay.

A powerful case can be made for racial equity on economic terms alone. For example, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s 2018 Business Case for Racial Equity found that Michigan could boost its economic output by $92 billion by 2050 if it closes the racial equity gap. PolicyLink’s 2019 Equitable Growth Profile of the City of Long Beach (CA) shows the economy of the Los Angeles region would have been $502 billion higher in 2015 if racial gaps in income were closed. According to the data, when racial inequities are addressed, economic gains benefit everyone.

Racial and other categories of inequity (e.g., those based on gender, ability, status, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and religion) limit the ability of people to fulfill their potential and thrive. The loss to the country in terms of productivity, tax revenues, innovation, and social cohesion is compounded by the costs of addressing health, education, and economic harm inflicted by structural racism, not to mention the wasteful quagmire of social unrest.

With so much to gain, what is holding us back? Bias, misunderstanding and fear cause us to act in ways that are contrary to the best interests of our country—and ourselves. A recent example in education is a situation in Missouri where a district superintendent received death threats and community resistance for his plan to hire a firm to carry out racial equity training for teachers and staff.

Fear of political backlash, of organizational change or of addressing what Susan Gooden characterizes as a, “Nervous area of government,” are the main reasons public administrators avoid addressing social equity. The most common reason given is that resources and financial constraints prevent allocating any funds to advance equity—even before considering what the cost, if any, might be or whether outside funding might be available to support it. While government budgets are shrinking, the, “Budget constraints,” argument is short-sighted and only serves to deepen structural racism, which costs us more in the long run.

Other public administrators cling to the traditional but outdated model of prioritizing efficiency above all else. Overly simplistic, it precludes questioning the effects of decisions and policies in favor of expediency. Like the, “Budget constraints,” rationale, it provides short-term political cover, but does nothing to address equity and exposes government to the risk of lawsuits and reactive management.

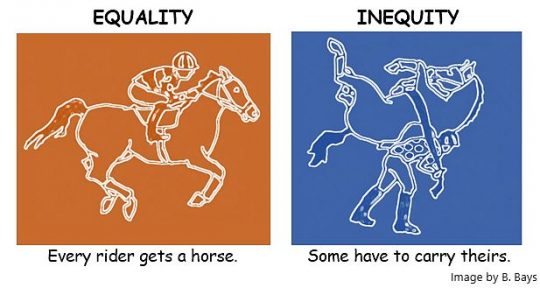

Another form of resistance occurs when administrators and employees misunderstand what the term equity means. Those who think equity is the same thing as equality may believe that equity has already been accomplished.

Successful attempts at equity programs have hinged on the strong support of upper management. The lauded example set by Seattle’s Race and Social Justice Initiative was an effort sustained over the long-term by two mayors. Seattle’s leadership communicated the clear expectation that equity mattered when it required all employees (over 8,000) to undergo intensive racial equity training.

Yet, equity training may be ineffective for a number of reasons, most especially, because of the tendency towards one-off programs rather than sustained efforts or that trainers have not thoroughly taken into account the research on why some programs succeed and others fail.

Effective equity initiatives cannot flinch at talking about systemic racism, but the messaging needs to be adaptable. As noted in Diane J. Goodman’s book, Promoting Diversity and Social Justice, facilitators need to be aware that people approach the topic from varying perspectives and with different experiences, knowledge, expectations and biases about diversity and social justice. For this reason, a key strategy in reaching resistant or closed minds is to initially avoid triggering knee-jerk reactions to politicized or loaded terms. The goal is to keep the corridors of thought open long enough to allow for authentic engagement.

Highly polarized environments and the lack of supportive leadership can undermine manager’s efforts to start a conversation about equity. In the void of leadership initiative, flexibility in communication can support the marshaling of a bottom-up approach by employees to press leadership to take up the equity challenge.

Author: Parisa Vinzant is a consultant, MPA-seeking student (Biden School of Public Policy and Administration, University of Delaware), and technology/innovation commissioner in Long Beach, CA. Through her writing, Parisa seeks to apply a diversity, inclusion, and social/racial equity lens to such topics as infrastructure and technology, revitalizing the middle class, and community engagement. Contact her at [email protected] and @Parisa_Vinzant (Twitter).

Parisa Vinzant

September 30, 2019 at 4:41 pm

Hi Madison, Thank you for your feedback! I appreciate your insights. I too am concerned with the lack of actual implementation of equity initiatives. I am continuing to research in this area and looking for potential collaborators if you or someone you know may be interested. Thanks!

Madison Sampson

September 23, 2019 at 2:52 pm

Great post! I’m deeply concerned with the lack of actually implementation of equity initiatives, despite the fields awareness of the benefits. I appreciate the discussion here about reasons that may be the case and hope more managers embrace having on-going DEI trainings instead of one-offs.