The Human And Financial Toll of Hurricanes: Where Does The Country Go From Here?

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Philip M. Nufrio, Roseanne Mirabella and Bev Cigler

November 5, 2019

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), since 1980 the United States has sustained 219 weather and climate disasters of all types. Damage costs per disaster reached or exceeded $1 billion (including Consumer Price Index adjustments through December 2017), with the cumulative costs for the 219 events exceeding $1.5 trillion. Fewer lives are lost to natural hazards in recent years due to better forecasting, warning and emergency response. There are, however, disproportionate effects on people and groups in terms of their ability to anticipate, cope with and recover from disaster events with special needs populations often the most vulnerable.

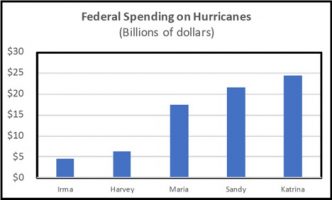

In Disaster Politics and Policy (2019), Sylves reports that 2017 was a record-breaking year for the United States on hurricane damages, with 10 hurricanes that collectively inflicted $265 billion in damages. Table 1 shows federal spending as of April 30, 2018 for the five most financially devastating storms since 2005. Federal spending for Maria, Harvey and Irma will continue for ten more years and may exceed spending for Hurricanes Ike, Sandy, Rita and Wilma.

Table 1: Federal Spending on Hurricanes (2005 – Present)

2019 ASPA Panel

At ASPA’s 2019 conference, Professor Phil Nufrio, Metropolitan College of New York, chaired a panel on hurricanes that included: U.S Representatives Garret Graves (R), District 6, Baton Rouge, Louisiana and Stacey Plaskett, (D) U.S. Virgin Islands; Mark S. Roupas, Deputy Chief, Office of Homeland Security, United States Army Corps of Engineers (Corps); Penn State Distinguished Professor Emerita, Beverly A. Cigler; and moderator Professor Roseanne Mirabella, Seton Hall University. Highlights from the panel are summarized here.

Climate Change and Its Impact on Disasters

The 2017 NOAA report shows United States temperature warming at a rate of at least 2.0 °F per century over the northern third of the United States and sea levels rising on the Gulf and Atlantic coastlines. New York Harbor following Hurricane Sandy saw sea levels rise one foot higher than a century ago, contributing to destruction in large parts of New York City. Identical outcomes affected large parts of the other devastating storms since 2005 (Table 1) and the surrounding coastal cities.

Panelists discussed the relationship between climate change and extreme events and effects on decisionmaker responsibilities for life safety considerations and large infrastructure investments. The obvious changes in rising sea levels and their associated impacts on storm surge suggest some bipartisan progress on working together to seek common ground on addressing climate change.

Flood Risk Mitigation

Flood risk mitigation consists of actions that reduce risk to people and property from hazards and their affects. Mitigation tools include design and construction applications, such as elevation of homes; land use planning and zoning; and shoreline structural protection. Enacted in 1968, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is the most widely used flood risk mitigation tool. It’s intended to encourage individuals living in hazard-prone areas to purchase insurance on the assumption that a government subsidized program will entice purchases of policies that minimize the need for federal post-disaster assistance. Such policies encourage the use of an array of mitigation tools.

Too few property owners purchase NFIP policies. Between 1972 and 2017 real dollar damages exceeded insurance payouts and placed a huge burden on direct federal assistance and FEMA’s budget. Only 40% of Hurricane Katrina victims in Mississippi and Louisiana had NFIP insurance and only 15% of the homes impacted in the Houston area were covered by the NFIP when Hurricane Harvey struck in 2017. There is a pattern of insurance underpayments even for individuals who have NFIP and private insurance and, since Katrina, many NFIP policy holders have had their claims denied. The panelists discussed challenges facing the NFIP, stressing the difficulties of determining risk and how it is apportioned to the property owner, the state and the federal government.

Spending on Recovery vs. Mitigation

The panelists questioned if perhaps instead of continuing to expend large amounts of taxpayer dollars on disaster response and recovery, a more cost efficient approach might be considered since dollars spent on mitigation can greatly reduce recovery costs and provide a better return on investment. The federal government pays 75% of disaster costs, but only $1 in $10 goes to mitigation. Leverage is gained through strengthened zoning and building codes (state and local responsibilities) and enabling federal mitigation funding. Costly structural projects such as levees and dune replenishment remain a key national responsibility.

Panelists were in agreement that the Disaster Assistance and Recovery Act of 2018, under which 6% of the authorized FEMA disaster relief funds are earmarked for mitigation depending on the severity of disasters for a given year, is promising. Congress annually approves coastal mitigation projects done by the Corps that positively impact coastal communities. For example, after Hurricane Sandy 150 miles of beaches were added to the Northeast corridor. These additional beaches do require financial demands on the federal government to partner with non-federal partners, usually a mandated 65/35 split (federal/non-federal share).

Each coastal storm risk management project is congressionally authorized. Non-federal sponsors assume operation and maintenance after initial construction and routine nourishment involves a cost share agreement. Hard structures such as seawalls, surge barriers, etc. may also be needed and Congress can authorize supplemental appropriations for them.

Concluding Observation

The costs of extreme weather events increase as climate changes and the intensity and frequency of heavy precipitation events has increased in most parts of the United States since 1901. The northeast has the largest increases in heavy precipitation and local relative sea level rise. Scientists expect continued changes in riverine, coastal, and combined flooding as climate continues to change.

Post-Hurricane Dorian and Tropical Storm Imelda thinking requires more serious consideration of mitigation. There is renewed interest in well-managed retreat and relocation of some people and communities. Respect for good science and cooperation across sectors and regions is of concern. As mentioned at the beginning of this essay, the most socially vulnerable often suffer the most in a disaster and emergency management is increasingly looked upon as a part of social welfare policy.

Author: Philip M. Nufrio, Professor, School of Public Affairs and Administration, the Metropolitan College of New York. Dr. Nufrio is a Hurricane Sandy survivor. His residence in New Jersey was destroyed by Superstorm Sandy. Roseanne Mirabella, Professor Seton Hall University. Bev Cigler, Professor Emerita, Penn State University, Harrisburg.

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

(1 votes, average: 5.00 out of 5)

Loading...

Loading...

The Human And Financial Toll of Hurricanes: Where Does The Country Go From Here?

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Philip M. Nufrio, Roseanne Mirabella and Bev Cigler

November 5, 2019

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), since 1980 the United States has sustained 219 weather and climate disasters of all types. Damage costs per disaster reached or exceeded $1 billion (including Consumer Price Index adjustments through December 2017), with the cumulative costs for the 219 events exceeding $1.5 trillion. Fewer lives are lost to natural hazards in recent years due to better forecasting, warning and emergency response. There are, however, disproportionate effects on people and groups in terms of their ability to anticipate, cope with and recover from disaster events with special needs populations often the most vulnerable.

In Disaster Politics and Policy (2019), Sylves reports that 2017 was a record-breaking year for the United States on hurricane damages, with 10 hurricanes that collectively inflicted $265 billion in damages. Table 1 shows federal spending as of April 30, 2018 for the five most financially devastating storms since 2005. Federal spending for Maria, Harvey and Irma will continue for ten more years and may exceed spending for Hurricanes Ike, Sandy, Rita and Wilma.

Table 1: Federal Spending on Hurricanes (2005 – Present)

2019 ASPA Panel

At ASPA’s 2019 conference, Professor Phil Nufrio, Metropolitan College of New York, chaired a panel on hurricanes that included: U.S Representatives Garret Graves (R), District 6, Baton Rouge, Louisiana and Stacey Plaskett, (D) U.S. Virgin Islands; Mark S. Roupas, Deputy Chief, Office of Homeland Security, United States Army Corps of Engineers (Corps); Penn State Distinguished Professor Emerita, Beverly A. Cigler; and moderator Professor Roseanne Mirabella, Seton Hall University. Highlights from the panel are summarized here.

Climate Change and Its Impact on Disasters

The 2017 NOAA report shows United States temperature warming at a rate of at least 2.0 °F per century over the northern third of the United States and sea levels rising on the Gulf and Atlantic coastlines. New York Harbor following Hurricane Sandy saw sea levels rise one foot higher than a century ago, contributing to destruction in large parts of New York City. Identical outcomes affected large parts of the other devastating storms since 2005 (Table 1) and the surrounding coastal cities.

Panelists discussed the relationship between climate change and extreme events and effects on decisionmaker responsibilities for life safety considerations and large infrastructure investments. The obvious changes in rising sea levels and their associated impacts on storm surge suggest some bipartisan progress on working together to seek common ground on addressing climate change.

Flood Risk Mitigation

Flood risk mitigation consists of actions that reduce risk to people and property from hazards and their affects. Mitigation tools include design and construction applications, such as elevation of homes; land use planning and zoning; and shoreline structural protection. Enacted in 1968, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is the most widely used flood risk mitigation tool. It’s intended to encourage individuals living in hazard-prone areas to purchase insurance on the assumption that a government subsidized program will entice purchases of policies that minimize the need for federal post-disaster assistance. Such policies encourage the use of an array of mitigation tools.

Too few property owners purchase NFIP policies. Between 1972 and 2017 real dollar damages exceeded insurance payouts and placed a huge burden on direct federal assistance and FEMA’s budget. Only 40% of Hurricane Katrina victims in Mississippi and Louisiana had NFIP insurance and only 15% of the homes impacted in the Houston area were covered by the NFIP when Hurricane Harvey struck in 2017. There is a pattern of insurance underpayments even for individuals who have NFIP and private insurance and, since Katrina, many NFIP policy holders have had their claims denied. The panelists discussed challenges facing the NFIP, stressing the difficulties of determining risk and how it is apportioned to the property owner, the state and the federal government.

Spending on Recovery vs. Mitigation

The panelists questioned if perhaps instead of continuing to expend large amounts of taxpayer dollars on disaster response and recovery, a more cost efficient approach might be considered since dollars spent on mitigation can greatly reduce recovery costs and provide a better return on investment. The federal government pays 75% of disaster costs, but only $1 in $10 goes to mitigation. Leverage is gained through strengthened zoning and building codes (state and local responsibilities) and enabling federal mitigation funding. Costly structural projects such as levees and dune replenishment remain a key national responsibility.

Panelists were in agreement that the Disaster Assistance and Recovery Act of 2018, under which 6% of the authorized FEMA disaster relief funds are earmarked for mitigation depending on the severity of disasters for a given year, is promising. Congress annually approves coastal mitigation projects done by the Corps that positively impact coastal communities. For example, after Hurricane Sandy 150 miles of beaches were added to the Northeast corridor. These additional beaches do require financial demands on the federal government to partner with non-federal partners, usually a mandated 65/35 split (federal/non-federal share).

Each coastal storm risk management project is congressionally authorized. Non-federal sponsors assume operation and maintenance after initial construction and routine nourishment involves a cost share agreement. Hard structures such as seawalls, surge barriers, etc. may also be needed and Congress can authorize supplemental appropriations for them.

Concluding Observation

The costs of extreme weather events increase as climate changes and the intensity and frequency of heavy precipitation events has increased in most parts of the United States since 1901. The northeast has the largest increases in heavy precipitation and local relative sea level rise. Scientists expect continued changes in riverine, coastal, and combined flooding as climate continues to change.

Post-Hurricane Dorian and Tropical Storm Imelda thinking requires more serious consideration of mitigation. There is renewed interest in well-managed retreat and relocation of some people and communities. Respect for good science and cooperation across sectors and regions is of concern. As mentioned at the beginning of this essay, the most socially vulnerable often suffer the most in a disaster and emergency management is increasingly looked upon as a part of social welfare policy.

Author: Philip M. Nufrio, Professor, School of Public Affairs and Administration, the Metropolitan College of New York. Dr. Nufrio is a Hurricane Sandy survivor. His residence in New Jersey was destroyed by Superstorm Sandy. Roseanne Mirabella, Professor Seton Hall University. Bev Cigler, Professor Emerita, Penn State University, Harrisburg.

Follow Us!