Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

To Fold or Not to Fold? Playing Poker with Tax Incentive Bidding for Amazon’s HQ2

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Nicholas Mastron

June 8, 2018

Perhaps the hottest public finance topic of the last year has been Amazon’s intent to build a second headquarters (HQ2) somewhere in the United States or Canada. A million questions surround this pivotal private sector expansio: how many jobs will be created; what will the functionality of the second headquarters be; what does the supporting economic development look like?

However, what is known, at least for the finalist cities, are some of the tax incentives packages being offered as tribute to sway Amazon to their respective locales. While analyzing which cities are best for Amazon would be worthwhile, a deeper impact assessment is first needed to determine if these cities are truly playing poker with their incentives or merely folding on a bad hand.

To realize these cities’ economic outlook, two major components must be analyzed: 1) cities’ tax abatement strategies to spur current and future economic activities; and 2) direct political power bestowment to a particular firm.

Tax Abatement Strategies

Incentivizing cities’ economic development presents a difficult challenge to mayors, managers and councilmembers alike, as few tools exist to attract corporate investment. The primary tools municipalities employ are tax abatement strategies.

The 1960s witnessed the beginning of many cities’ widespread decline in property and corporate tax bases through both resident and firm relocation to newly inhabited suburban areas, now connected by interstates and highways. Hence, economic support for local businesses diminished.

Theoretically, abating certain taxes enables a firm to reach a faster degree of economies of scale regionally, thereby fostering faster contributions to support the local economy. Furthermore, many incentives are linked to public goods and infrastructure improvements, not to mention partnerships with other local businesses. As urban policy literature attests, some cities, facing decreased abilities to supply public goods as well as economic opportunities to residents, attract new firms to then bolster supporting firms.

In actuality, numerous pitfalls inhibit this reality. First, many firms do not decide their ultimate firm location based off tax incentives. Another caveat is that companies will often undermine cities’ and states’ economic sustainability by “playing one city’s incentives against another.” Moreover, by aggressively engaging local officials, social costs ensue from other businesses, both small and large, that feel relegated for not receiving the same caliber treatment (not to mention the potential alienation of citizens).

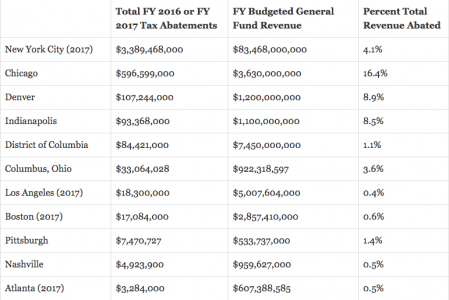

Yet, cities remain convinced that these incentives serve as the best way to attract businesses like Amazon, as you can see from those recently reported to Governmental Accounting Standards Board figures below. While this chart obviously does not capture those offered to Amazon, one can already see the monumental revenues foregone in the immediate, let alone future revenues.

Direct Political Power

A second element to analyze is the offering of direct political power to Amazon. Now, some readers may balk at this idea entirely as preposterous, but several cities have publicly disclosed their intents to create everything from taskforces, specific education incentives and living spaces for HQ2. While these particular incentives may not inherently seem directly political, the implications are far-reaching.

Boston, for example, has commissioned a direct Amazon taskforce to be connected with local government. This would create a direct government-funded link between the city and the company, which bestows enormous agenda-setting power potential at the local, and in the Boston case) regional level.

Another common incentive is the offerings of higher educational pipelines that would feed into HQ2’s Big Orange Machine. In the short-term, this type of proposal would enhance Amazon’s human capital needs for training, but at some costs.

These incentives could lead to decreased local residents’ attending higher education institutions, prompting a crowding out effect, although recent data somewhat dispels this concern. Conversely, these incentives might also trigger rapid expansion to absorb the population shocks, which then leads to more abated property through university expansion and acquisition since higher education institutions submit lower payments-in-lieu-of-tax (PILOTs) than the normal corporate property taxes.

Other cities, like New York, have promised living areas to be specifically designed for incoming Amazon employees. This residential promise encompasses an inherent but inequitable relocation for poorer long-term residents. Similar to the educational offerings, these living space designations could directly allow Amazon more power in zoning decisions through crowding out other business or citizen concerns.

Outlook

All in all, cities should proceed with great caution before offering massive incentive packages to businesses like Amazon because in many cases they effectively present naturally attractive advantages. For example, Nashville, who refused to make any public incentives for Amazon, houses a fairly low cost of living, access to the Interstate 40 corridor and a large area for expanded development as operations grow. Similar stories exist for Dallas and Austin as well.

Amazon is still but one business, so maintaining that narrow perspective blinds cities to more holistic perspectives could yield more better economic engineering for the long-term. Cities should not be folding before even the ante’s been played, because Amazon may very well only have pocket twos.

Author: Nicholas Mastron is a current doctoral student in Public Policy & Administration at the George Washington University, with a field specialization in Social & Gender Policy. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him @NicholasMastron. The views expressed in this article solely reflect the author’s opinions and not those of any employer, university, or professional association that which he may associate.

Follow Us!