Widgetized Section

Go to Admin » Appearance » Widgets » and move Gabfire Widget: Social into that MastheadOverlay zone

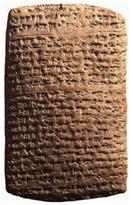

Written in Stone: The Daunting Inflexibility of Public Policy

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ASPA as an organization.

By Burden S Lundgren

March 15, 2016

Public policy is hard to make. It can take months, years or even decades. Passing the necessary statutes and writing the regulations bring both exhilaration and exhaustion on the part of supporters. The very last thing they want to do is critically analyze the unanticipated and sometimes negative consequences of their policies, let alone address them.

Public policy is hard to make. It can take months, years or even decades. Passing the necessary statutes and writing the regulations bring both exhilaration and exhaustion on the part of supporters. The very last thing they want to do is critically analyze the unanticipated and sometimes negative consequences of their policies, let alone address them.

Policy in public health is particularly problematic. Policy should be based on sound science, but often isn’t. More difficult still is policy that is based on science, which then changes. Take cancer screening as an example. Just as the notion of screening has been firmly embedded in public policy (largely by mandating payment for screening tests and “educating” the public as to their necessity), scientists are questioning whether mass cancer screenings have any effect on mortality at all.

But most troubling of all is public policy that incentivizes the long-term survival of a problematic program. The example I want to discuss is a technology used by millions of patients: dialysis for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). As aging occurs, the kidneys become less efficient and kidney failure becomes common. There are many diseases that cause or predispose kidney failure at any age especially diabetes, high blood pressure or autoimmune conditions. Kidney disease is usually progressive. In its final stage, it is uniformly fatal. An estimated 26 million Americans have chronic kidney disease (CKD). More than half a million of these are advanced enough to require dialysis or transplantation for survival.

As early as 100 CE, the Romans used hot baths to try to sweat out the accumulating toxins of kidney disease. Thomas Graham, a 19th-century chemist, developed the separation techniques that are still the basis of kidney dialysis. An artificial kidney for animal use was invented in 1913, but it was not until 1945 that a Dutch physician conducted the first dialysis treatment on humans. And it was not until 1960 that a Boeing machinist suffering from chronic renal failure became the first patient to be treated with ongoing hemodialysis. He survived for 11 years.

Almost immediately two serious problems developed. First, there were not enough machines and personnel to address the overwhelming need. Second, the treatment was beyond the financial means of almost all prospective patients. Not surprisingly, the notion of denying life-saving treatment to thousands of Americans became a political problem. The federal government established dialysis programs in 30 Veterans Affairs hospitals in 1963. Ten years later, Medicare began paying for dialysis. This was public policy meeting public need. It sounds exactly like what a public program should do.

With the program well into its fifth decade, where we are now? Does dialysis extend life? Yes, but with a five-year survival rate of 38.5 percent and a questionable quality of life where many patients choose not to continue treatment.

As policy is resistant to change, the program is a perfect storm: a chronic, life-threatening disease, a patient population that is disproportionately minority (35 percent of dialysis patients are African-American), a technology controlled by for-profit companies and funded by the federal government. All the incentives are set to allow kidney disease to run its course to complete failure and then treat.

There is still no specific treatment for progressive CKD. However, compare kidney disease to heart disease. Cardiologists have an arsenal of interventions to prevent the incidence and/or progression of pathology and another arsenal of technical interventions when the disease does progress. Indeed, what medical specialty other than nephrology sits back and waits for the worst to happen and then relies on mid-20th-century technology as its main therapeutic measure?

Not only is this questionable for patients, but also it is expensive for taxpayers. Every year, Medicare spends nearly $21 billion on ESRD patients, including $72,000 for each patient on dialysis. This represents a full 28 percent of Medicare spending. (Interestingly, transplant patients survive three times longer than dialysis patients and at a far lower cost. However, there are three times as many patients on the active waiting lists as there are donors.)

Is simply monitoring disease progression and providing a poor quality of life, at very high costs, the best we can do? Consider heart disease again. The NIH funds research for heart disease at $1.3 billion annually and a little more than $500 million for kidney disease. It is no wonder there has been little progress in treating kidney disease.

This is not 1960. Kidney disease patients need interventions to prevent end-stage failure. Taxpayers need relief from ongoing payments for a technology that should be obsolete. What is the best use of public funds now? We have invested heavily in heart disease research and that investment has paid off. Increased investment in kidney disease research is justified based on cost savings alone.

However, the issue is larger than this one program. Public policy should meet public needs and public needs change. That calls for periodic program evaluation. Neither statutes nor regulations should be written in stone.

Author: Burden S Lundgren, MPH, Ph.D., RN, practiced as a registered nurse specializing in acute and critical care. After leaving clinical practice, she worked as an analyst at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and later taught at Old Dominion University. Presently, she divides her time between Virginia and Pennsylvania and is working on two books – when her cocker spaniels let her. Email: [email protected].

Follow Us!